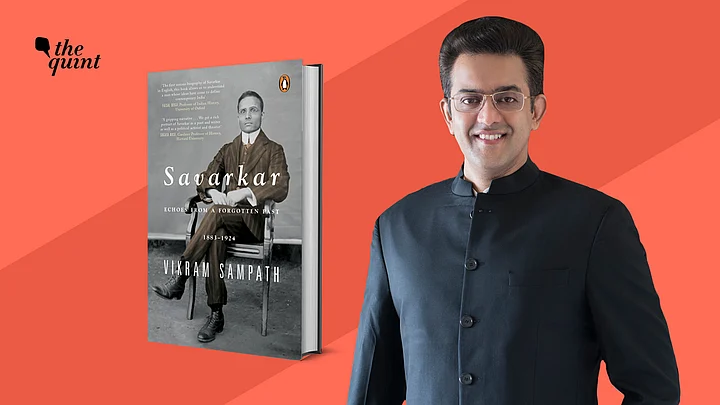

Between being the original ‘poster boy’ of hardcore Hindutva, and being reviled for what the Left calls his ‘communal sectarianism’, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar’s name has come to elicit a variety of responses. On the occasion of the release of author and historian Vikram Sampath's latest book ‘Savarkar: Echoes from a Forgotten Past, 1883–1924’, Yogesh Pawar spoke to him in the backdrop of a sociopolitical climate that many perceive to be coloured by Hindu majoritarianism.

Below are excerpts from the interview:

Why a book on Savarkar now?

If not now, then when? At a time when his name is getting dragged into every contemporary political discourse; with Rahul Gandhi making defamatory remarks about him to Narendra Modi paying homage to him in his cell at the Cellular Jail — the diurnal opinions about his so-called ‘mercy petitions’, the decision of the Rajasthan government to drop the ‘Veer’ from his name in textbooks... all these show not only a great interest in the man, but also the constant attempts to either sully/glorify him...It becomes a historian’s burden to make the facts available as they are to the discerning readers, so that they can make up their minds on their own and realise there are really no black and white answers when it comes to history...

‘Opening Up A New Dimension To Savarkar’s Life’

Can you walk us through your journey with the book? When did you first think of the idea? How long did it take to finally emerge as the book?

Savarkar has been an addiction since I first heard about him in 2003-04 after the controversy over his plaque at Andaman’s Cellular Jail was dislodged at Mani Shankar Aiyar (then Petroleum minister)‘s behest. We had no reference to Savarkar in schoo; I’d studied in the CBSE and ISC syllabus. Yet, this figure from the past keeps intruding contemporary political discourse... However, it’s only in the last 3-4 years that I managed to get down to serious research around him. A senior fellowship from the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (NMML) further aided this process. I was quite amazed to know that a man who evokes such strong, polarising reactions even now, and whose philosophy and thoughts have shaped India in so many ways and continue to do, has been so less researched or written about. I’ve been rummaging several archives across India and abroad, gathering original archival and court documents... A lot of information about Savarkar, and also his own writings, are in Marathi. These have seldom been accessed by mainstream historians. Accessing these opened up a new dimension to the man’s life and vision, and helped clear the cobwebs history and politics have shrouded his image in.

“The British Were Petrified Of Savarkar”

Sampath added that, “Interviews with old-timers, Savarkar’s proponents and opponents, and support from his family, especially his grandnephew Ranjit Savarkar (who heads the Savarkar Smarak in Mumbai), travels to various places associated with him from Bhagur, Nashik, Port Blair, Mumbai, London etc completed the research journey. This, incidentally, is just the first in the two-volume book which covers the story of his life from his birth in 1883 to his conditional release to Ratnagiri in 1924.”

As a leader, Savarkar elicits extreme responses. Some worship him, while others revile him as a traitor who capitulated to the British and tried to break the unity of the freedom movement on sectarian lines. Your take?

I think a lot of the so-called “traitor” related controversy is of recent vintage — post the Mani Shankar Aiyar episode. A deliberate narrative of calumny has been built. On his death in 1966, the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had famously said: “It removes from our midst a great figure of contemporary India. His name was a byword for daring and patriotism. Mr Savarkar was cast in the mould of a classical revolutionary and countless people drew inspiration from him.” So, was a great former PM and a Congress leader endorsing a “traitor” then?

All through his youth, Savarkar was a firebrand revolutionary, credited with forming one of the first organised secret societies in India — the ‘Mitra Mela’ (later became Abhinav Bharat) that called for total and complete freedom in the early 1900s. His five years in London were stormy, as he built a vast network of revolutionaries across Europe, orchestrated bombings and political assassinations, and also produced a huge corpus of intellectual output for the revolutionary movement. The British were so petrified of him that they wanted him deported to India and thrown in the worst and most inhuman conditions in Cellular Jail in the Andamans — far away from mainland India — for 50 years.

Was Savarkar Really A British ‘Stooge’?

And the ‘Mercy Petitions’ Savarkar Wrote...

Being a barrister, Savarkar knew the law and its loopholes and wanted to use every means available to free himself. He advised fellow revolutionaries too to sign these petitions and promise whatever the British asked them to but carry on with their work... In the petitions that Savarkar submitted from 1914 to 1924, he maintained that when common convicts of rape, theft or murder were let out.... after six months, other political prisoners like him were not allowed similar facility since they were ‘special class prisoners’. And when they asked for privileges befitting their status — such as meeting one’s family, writing regular letters or reading books — they were denied... This double disadvantage was unfair, he argued... The last line of his 1914 petition, that often gets quoted, is: “The mighty alone can afford to be merciful, and therefore, where else can the prodigal son return but to the parental doors of the government?” In his 1917 petition, Savarkar states: “If the government thinks that it is only to affect my own release that I pen this; or if my name constitutes the chief obstacle in the granting of such an amnesty; then let the government omit my name in their amnesty and release all the rest; that would give me as great a satisfaction as my own release would do.”

Do these sound like the words of a coward or a British stooge? Later too... his support in the revolutionary movement, be it with Bhagat Singh or Subhash Chandra Bose for whose INA he was helping recruit soldiers, and which was acknowledged by Netaji and Rash Behari Bose, certainly shows that the truth lies elsewhere.

Savarkar On Caste, And Beef Consumption

Savarkar’s take on Hinduism does not make space for caste. It is something even Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar brought up. Does your book explore that?

This volume (of the series) does draw upon some of his writings and thoughts on the issue. It becomes clear that there was more convergence of views on this topic between Savarkar and Ambedkar, and Gandhi was on another tangent. Savarkar stressed repeatedly in his writings and actions about how the caste system had nothing to do with Hinduism or the Sanatan Dharma. Taking a radical stand against those scriptural injunctions that advocated caste, he said fossilising oneself to them was idiocy. These scriptures that were often self-contradictory, according to Savarkar, were created by human beings, and were relevant in a particular context and in a particular society. They need to evolve or be discarded as society moves ahead. He viewed the caste system as an evil that splintered and disunited Hindu society, making it susceptible to attacks and conversions by other groups. He called for a complete abandonment of what he called “the seven fetters” that held the Hindu community back — restrictions on inter-caste dining, inter-caste marriage, lack of access to scriptures, heredity of profession, untouchability, strictures on crossing the sea, disallowing reconversions (shuddhi). This was for a powerful consolidation of the Hindu society sans all its deep fissures.

Since Savarkar saw nothing wrong in beef consumption, what do you think he would have made of the current lynchings by cow-vigilantes or the attempts to homogenise Hinduism as an upper-caste, upper-class cow belt variation of a vegetarian-only religion?

Many of Savarkar’s social reform measures earned the ire of the local Brahmin community. This included the advocacy of large scale inter-caste dining and the establishment of a ‘Patit Pavan’ (literally meaning the protector of the fallen) temple that allowed entry to members of all castes for community prayers. Savarkar held radical views on matters like cow-worship.

“We Become The God We Worship”: Savarkar

Savarkar wrote, “Animals such as the cow and buffalo and trees such as banyan and peepal are useful to man, hence we are fond of them; to that extent, we might even consider them worthy of worship. Their protection, sustenance and well-being is our duty, in that sense alone it is also our dharma!”

Vikram Sampath went on to add, “But he (Savarkar) cautioned that if the ‘animal or tree becomes a source of trouble to mankind, it ceases to be worthy of sustenance or protection, and as such its destruction is in humanitarian or national interests, and becomes a human or national dharma. When humanitarian interests are not served and in fact harmed by the cow, and when humanism is shamed, self-defeating extreme cow protection should be rejected.’ Savarkar has appropriate advice for cow-vigilantes meting out instant mob-justice with lynchings!”

According to Vikram Sampath, Savarkar went on further to assert that while he held the cow as a “beautiful creature,” protecting it and not worshipping it like a goddess was his belief. Elevating an animal that often eats garbage and sits in its own excreta to the position of a goddess, even while society disrespected scholars like Ambedkar and Chokha Mela due to their supposed low-caste was “insulting both humanity and divinity,” opined Savarkar.

“We become the God we worship, and hence, Hindutva’s icon should be the Narasimha or fierce man-lion and not the docile cow,” wrote Savarkar.

“I am no enemy of the cow,” he said, “I've only criticised the false notions and tendencies involved in cow-worship with the aim of removing the chaff and preserving the essence so that genuine cow protection may be better achieved. Without spreading religious superstition, let the movement for cow-protection be based and popularised on clear-cut economic and scientific principles. A worshipful attitude is undoubtedly necessary for protection. But it is improper to forget the duty of cow-protection and indulge only in worship.”

(Yogesh Pawar is a journalist for the past 24 years, and has worked with The Indian Express, NDTV, DNA. He tweets at @powerofyogesh.)

(Historian Vikram Sampath’s 624-page book, ‘Savarkar: Echoes from a Forgotten Past, 1883–1924’ has been published by Penguin, and costs Rs 999.)