(This is part three of a four-part 'August' series that revisits significant historical events or policies and how the lessons learned from them continue to be of relevance in present-day politics and society. Read part one here, part two here, and part four here.)

In India and Pakistan, the month of August is almost always associated with independence from the British (Pakistan on 14 August and India on 15 August) and partition. Many in India mark 14 August with sorrow and loss because of the millions that were killed in a frenzy of religious violence. Some patriotic Indians with a sense of history also celebrate 12 August.

That was the day Subhash Chandra Bose formed the 'Azad Hind Fauj' in 1942 and launched a military onslaught against the British Empire. Ironically, August 1942 is also when Mahatma Gandhi launched the Quit India movement.

All these momentous events no doubt, played a role in both eventual freedom and partition. Yet, in the personal opinion of both the authors, it was 16 August 1946, that finally made partition inevitable and impossible to avoid.

The Onset of Violence Between Hindus and Muslims

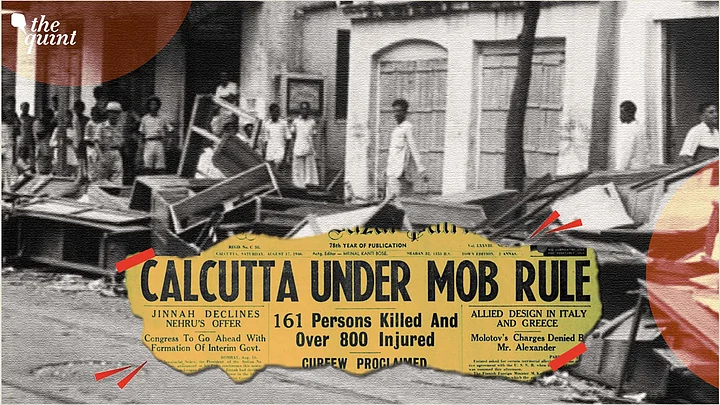

Strangely, many Indians have forgotten this but 16 August 1946 is when the Great Calcutta Killings took place. Till then, both Hindus and Muslims could think of a united India and dismiss the attacks and counterattacks by the Muslim League and the Congress as posturing and jockeying for power in a post-British India.

But all such dreams were shattered in an orgy of violence that started in Calcutta (Now Kolkatta) on 16 August and spread across many regions of undivided India for a week.

The Muslim League was strident in its demand for a separate nation for Muslims since 1940 when the party passed a formal resolution asking for a separate Muslim homeland.

But hopes of a united and free India were revived when the British government sent a Cabinet Mission in May 1946 to discuss the modalities of transferring power.

Both the Congress and the Muslim League agreed to the proposals of the Cabinet mission to set up a three-tiered structure of governance in a united and free India. Unfortunately, mutual mistrust was at its peak, each suspecting the other of acting perfidiously.

There was no shortage of hotheads and bigots to fuel further mistrust. By 1946, religious violence was becoming a frequent and commonplace occurrence though it was quickly dispelled too. Calcutta had witnessed short bouts of bloody riots in February and March, 1946. Anyways, amidst this simmering tension, Jawaharlal Nehru of the Congress said something about the Cabinet mission proposals in July.

The Inevitability Of Partition

Within a day, there was a sharp response from the Muslim League as it officially rejected the Cabinet Mission proposals. Before anyone could mediate further between the Muslim League and the Congress, Mohammed Ali Jinnah publicly called for a Direct Action Day on 16 August 1946, and proclaimed, "We (he meant Muslims) do not want war. If you (he meant Hindus & Sikhs) want war, we accept your offer, unhesitatingly. We will either have a divided India or a destroyed India."

These words and the monstrous violence that started on 16 August made even the great Mahatma Gandhi – a helpless and virtually irrelevant spectator as Hindus and Muslims that had co-existed for centuries despite differences and occasional riots marched inevitably towards Partition.

Perhaps, the Partition had become inevitable even in 1940 when Jinnah addressed the Lahore session of the All India Muslim League: “Hindus and Muslims belong to two different religions, philosophies, social customs, and literature…They have different epics, different heroes, and different episodes…to yoke together two such nations under a single state, one as a numerical minority and one as a majority must lead to growing discontent and the final destruction of any fabric that may be built up for the governance of such a state."

In hindsight, it seems top leaders of the Muslim League never had any iota of doubt that they were determined to carve out bits and pieces of India to form Pakistan.

Could millions of lives have been saved if the adversarial Congress and Muslim League talked dispassionately and agreed to a formal process of Partition? Such questions are impossible to answer; and history is littered with episodes and events when leaders have knowingly or unknowingly chosen the path of bloodshed, violence, and strife even when peaceful options were available.

Impact Of Direct Action Day

Calcutta became the epicentre of Direct Action Day violence for two reasons. First, communal riots had become increasingly frequent in Bengal in 1946. Tensions and mistrust between both communities were at a very high level. Second, the state was de facto ruled by the Muslim League with Hussein Suhrawardy as the chief minister.

The Muslim League decided to mark 16 August as a public holiday. British officials agreed as they thought closed markets and institutions would automatically mean less violence.

16 August was also a Friday when Muslims offered the important “Jumme Ki Namaaz”. Congress and Hindu Mahasabha leaders objected to the holiday saying it was tantamount to accepting the demand of Jinnah and surrendering Calcutta to the Muslim League. Anyways, many Hindu localities decided to not observe the holiday.

While accurate and completely reliable records are not available, there is enough evidence to suggest that Chief Minister Suhrawardy and other Muslim League leaders not only instigated Muslim mobs but also interfered with police operations to quell violence in a blatantly partisan way.

After being butchered by Muslim mobs on 15 August, Hindu and Sikh mobs started paying back in the same coin prompting Mahatma Gandhi to declare another fast unto death. It was the sheer moral force of Gandhi and some common sense that finally led to a halt to the bloodshed.

But the divide had become too big to bridge, no matter how hard the well-intentioned Mahatma tried.

The fact is, a population exchange started right after 16 August in the Bengal province. Muslims in the western part fled to the eastern parts where they were in the majority. Hindus in the eastern part did the same by fleeing to the western side.

What shocked many during then was not just the fact that such violence was unleashed during the holy month of Ramzan; but the realisation that top leaders of the Muslim League had no hesitation in using unrestrained violence as a political tool.

Lessons From History

The Great Calcutta Killings and the gory events preceding and succeeding it still have contemporary lessons. History has brutally demonstrated that religious identity cannot be the basis of a society and a nation-state on a stable and sustainable platform; particularly when you want to function as a democracy.

Mohamed Ali Jinnah wanted an Islamic nation-state where Muslims were safe and secure. The authors think millions of Indian Muslims after watching what has been happening in Pakistan will agree that Muslims are less safe in Pakistan than in India.

That religious identity cannot be the basis for a sustainable nation-state was demonstrated in 1971 when Bangladesh (erstwhile East Pakistan) became an independent nation-state.

While being Islamic, Bangladesh has paid more attention to modern-day governance and economic growth at the grassroots level. It is well ahead of Pakistan in economic terms. Meanwhile, Pakistan, that insists on religious identity as the foundation of its existence, is literally staring at the edge of an abyss.

Terrorism once targeted at Indian cities is now devouring Pakistan. It could never establish a functional democracy. It is economically and financially bankrupt, surviving on aid and loans. It looks doomed to remain a basket case.

(Yashwant Deshmukh & Sutanu Guru work with CVoter Foundation. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)