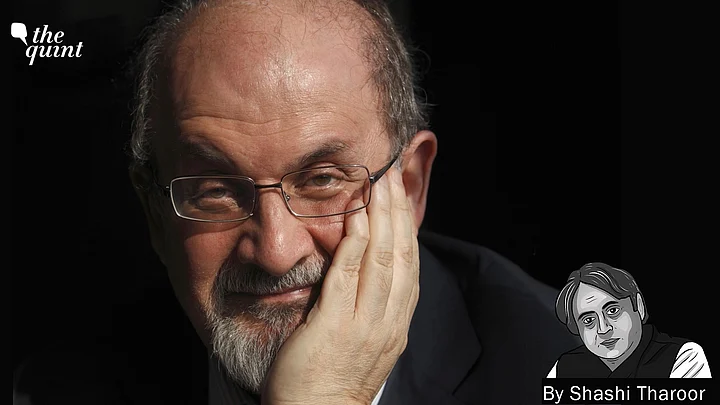

The shocking attack on Salman Rushdie at the Chautauqua Institution in New York state – which occurred, with savage irony, as he was being introduced to give a talk on artistic freedom – has left writers and readers alike stunned.

The author’s stabbing, which resulted in him being evacuated by helicopter to a hospital, in an unknown condition, can only have been prompted by the lingering resentment among some Muslims over his 1989 novel The Satanic Verses.

But 33 years after the original fatwa by Ayatollah Khomeini, calling upon Muslims to kill the novelist for blasphemy, which sent Rushdie into nine years of hiding, it is fair to say that few expected the threat to materialise now in an actual assault. The suspect, Hadi Matar, a 24-year-old man from Fairview, New Jersey, had not even been born when the original fatwa was issued.

Chilling Effect on Writers

The stabbing is, first of all, an unacceptable assault on freedom of expression. The reply to offensive words always ought to be with words, not knives or bullets. If writers have to go around fearing that their creative work could result in assassination, the threat of violence becomes an extreme form of censorship.

The attack also does a disservice to the Muslim community, raising the spectre of intolerance and violence that many are only too quick to associate with Islam. The episode will reinforce the prejudices of bigots everywhere against the religion and its adherents.

On a personal note, it saddens me to think that more and more writers and artists – and the events in which they appear – will need to adopt security measures.

While some Indian politicians might enjoy going around surrounded by security men, most normal human beings do not. We all value our privacy and personal autonomy.

The Norwegian and Japanese translators of the novel were murdered by Muslim fanatics in 1991. Rushdie stayed under police protection, living in secret addresses under pseudonyms (the most famous of which, “Joseph Anton”, is the title of his 2012 book describing those years) until the Iranian government declared in 1998 that it would no longer back the fatwa. However, Khomeini's successor as Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, did say in 2019 that the fatwa was "irrevocable".

Since 1998, Salman Rushdie has lived relatively openly and freely, attending public events, speaking on an assortment of stages, and even heading the writers’ organisation PEN. He has been knighted by the British government and became a US citizen in 2016. But we have sadly not been able to see much of him in India, where the threat perception remained high.

Life May Never Be the Same for Rushdie

I recall Rushdie, at the cusp of the millennium, strolling down a New York street alone to join me for lunch, feeling thrilled at being able to do so without needing security. It took almost a decade for him to regain that degree of normalcy. Those days are, sadly, now over for him and for those who would host him.

The perception will be that some writers who take on controversial issues cannot be put on a public stage without elaborate security precautions. This could be a dampener for those organisers who are unable or unwilling to take on such an additional burden. And it could restrict the opportunities available to such writers to reach a significant audience. That, too, could have a negative effect on freedom of expression.

The unpleasantness that most writers normally need to fear is a bad review; the worst might be a rotten egg or tomato hurled by an offended reader. You wipe the stain off and carry on. But according to his literary agent, Andrew Wylie, “Salman will likely lose one eye; the nerves in his arm were severed, and his liver was stabbed and damaged.” This is a high price for a 75-year-old writer to pay for his literary notoriety.

Ever since Midnight’s Children in 1981, Salman Rushdie, as a writer of the highest quality, has expanded the boundaries of the possible in his writing. Every Indian writer who has followed in his wake owes him a debt of gratitude for what he has accomplished. I wish him a speedy and complete recovery from his wounds, even though, with a sinking heart, I recognise that life for him can never be the same again.

(Dr Shashi Tharoor is a third-term MP for Thiruvananthapuram and award-winning author of 22 books, most recently ‘The Battle of Belonging’(Aleph). He tweets @ShashiTharoor. This is an opinion piece, and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)