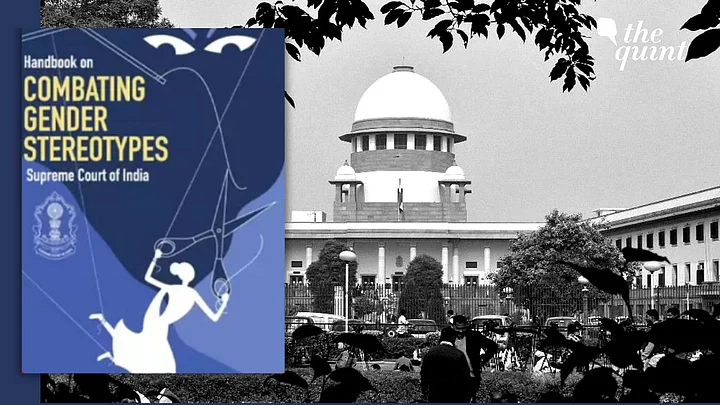

In a valiant attempt to tackle gender stereotypes that often find their way into judgments, the Supreme Court has released its “Handbook on Combating Gender Stereotypes”. This handbook purports to provide alternatives to commonly used terms in the legal discourse that often perpetuate gender stereotypes.

It further attempts to dislodge stereotypes confined to women, such as the absence of rational decision making faculties or how women who have children cannot possibly focus on their work.

The objective of the handbook is laudable and its worth lies in how a topic that challenges one’s innate understanding of gender has been dealt with in a language that is not complex, condescending or patronising.

It is not meant to shame the reader, here the lawyers and judiciary, but to make them encounter and comprehend their conditioning that has led to their thinking.

How Was This Change Initiated?

The endeavour towards progressive judgment writing received impetus in Aparna Bhat v State of Madhya Pradesh (2021) where the Supreme Court laid down the guidelines to address patriarchal notions being reproduced in court orders.

The issue in Aparna Bhat arose from a bail condition imposed by the High Court of Madhya Pradesh that required the applicant, who had been accused of outraging the modesty of a woman, to visit the house of the complainant in order to get a rakhi tied by the latter.

The condition imposed by the High Court led to a public outcry, with nine lawyers approaching the Supreme Court seeking a stay on the bail condition.

The judgment was a recognition of the shift that was required in the subconscious of those who interpret our laws and those who fight for our rights in courts.

It was a shift that indicated that neither did empowering women have to stem from a space of paternalism nor did the idea of a woman in the form of a mother or a wife have to emerge from gendered duties.

Furthering the aforementioned conversation, Chief Justice of India (CJI) DY Chandrachud had earlier this year revealed that a legal glossary of inappropriate gendered terms had been in the works for the past few years.

He observed that women in the legal profession, and elsewhere, were casually belittled due to preconceived notions harboured by not only men, but women themselves as well, and that the intent of the glossary was to face these biases instead of sidelining them.

What Does the Handbook Say?

The aim of the Handbook is to not only “avoid utilising harmful gender stereotypes”, but to actively challenge and dispel gender stereotypes.

As the Handbook states, it identifies language that promotes gender stereotypes and provides alternatives to it. It further challenges reasoning patterns that preserve such stereotypes and inequality. It lastly highlights decisions of the Supreme Court where judges have rejected gender stereotypes and adopted a progressive approach to case laws.

Many of the terminology which is sought to be replaced by the handbook results from sexual stereotypes which is technically a generalised view of the sexual characteristics or behaviours that women (and men) are expected to possess.

Women who engage in pre-marital sexual intercourse are largely believed to have “loose morals” or termed as “sluts”. In a bid to confront this manner of thinking, the handbook attempts to replace such wordings with the word “woman”.

A Leaf From Landmark Bhanwari Devi Case

Further, the handbook addresses stereotypes that are embedded in the subconscious of even the most progressive minded and charts a path to overcome these.

First and foremost, it asks us to reconsider certain assumptions that we make based on the “inherent characteristics” of women, and second, it requests us to make a conscious effort to resist and overcome these biases we bear.

Referring to Bhanwari Devi’s case, which led to the formulation of Vishaka Guidelines, and the later promulgation of the Prevention of Sexual Harassment at the Workplace Act 2013, the Handbook underlines how justice evaded Bhanwari Devi due to the trial court’s horrific observations such as how members of a dominant caste would not rape a woman from an oppressed caste.

Will the Handbook Facilitate Change?

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) had commissioned a study in 2013 to understand how gender stereotyping is a human rights violation, and how these stereotypes, specifically in the judiciary, can undermine justice for women.

The study analysed a few decisions that had been referred to the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW Committee).

One of the cases involved acquittal of a man in a rape case on account of the fact that the complainant had failed to escape the attack; another case concerned unlawful termination of employment which was based on extramarital affairs of men being condoned, but not of women.

Closer home, a prime example of how stereotypes are an antithesis to fair judicial decision-making would be the High Court of Karnataka’s judgment allowing an anticipatory bail application of the accused on the ground that the complainant had slept after being “ravished” and such behaviour was “unbecoming of an Indian woman."

The idea of how an “Indian woman” should behave after being sexually assaulted skewed the decision against the complainant, and was premised more on the subjectivity of the Judge rather than the legal principles which should have governed the grant of bail.

In such circumstances, the handbook strives to undo such patterns in decision making.

Further, apart from affecting the realisation of rights of women, gender stereotypes not only harm the treatment of women in workplaces, but also impact women’s self-conception. It impairs learning and prevents women from realising their full potential.

This is evident in lack of self-confidence and absence of assertion of boundaries that is displayed by women at their workplaces.

To grapple with this, the Supreme Court’s handbook is indeed an appreciable starting point to dismantle discrimination and inequality.

One can hope that its usage will extend beyond the legal circles and the handbook is read by all.

(Radhika Roy is a lawyer based out of New Delhi and former Associate Editor at LiveLaw. This is a personal blog and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)