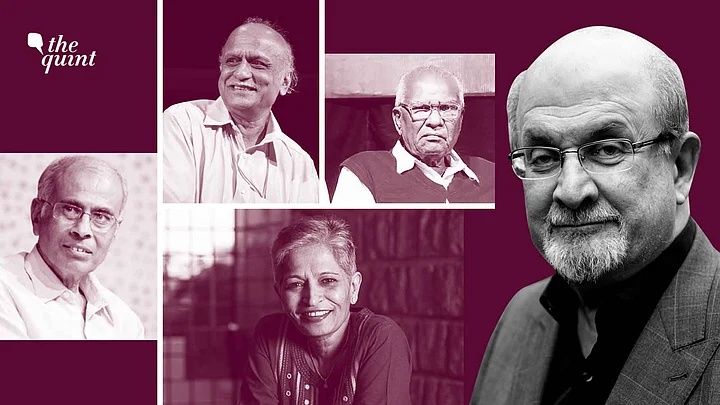

The attack on renowned writer Salman Rushdie, which he survived with the same grit that he displayed when he defied the 33-year-old grotesque fatwa by Iran, has shone the light on a sea of stories in his homeland.

The silence of the Indian government is jarring – particularly as India is closely linked to this – to Rushdie personally, his work, and the ban on his controversial book, The Satanic Verses. The silence may well be for tactical and ideological reasons of the current regime, but it is mainly because the attack on Rushdie cannot be seen by Indians in isolation of the attacks on its own writers and thinkers – those who are living under threat, and those who have been assassinated by haters keen on minimising their influence.

India Is No Longer 'Argumentative'

Today is the ninth anniversary of the fatal attack on writer and rationalist Dr Narendra Dabholkar, the founder of the Maharashtra Andhashraddha Nirmoolan Samiti, who was shot dead by two assailants while on a morning walk in Pune in 2013. A right-wing extremist organisation is said to be behind the assassination, and the reason is believed to be the take-down of blind faith, superstition and religion-based dogma that Dabholkar did with unrelenting determination. The Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) named five as accused in 2014, and the trial is still on. But there has been no conviction so far.

There have been other dead men and women since – Gobind Pansare and MM Kalaburgi, followed by Gauri Lankesh – who were killed for being effective writers and communicators, ones who defied narrow ideas that they passionately believed diminished humanity. Two right-wing extremist organisations are present through all the chargesheets, but the prosecution seems intent on not joining the dots.

India as a bustling haven of diversity and pluralism has taken a knock and the Indian is no longer cited as being ‘argumentative’, as the premium is on only ‘One India’, not many. This is reflected in indices of democracy that define India now as ‘partly free’.

Others have removed the term ‘democracy’ from their description. The V-Dem Institute reminded India in its 2022 report that India was among the top ten autocratising countries in the world and is now an ‘electoral autocracy’. But what do writers getting killed off or threatened have to do with this?

Why the State Is Threatened By Writers & Intellectuals

Plenty. The views of those who had mounted the attack on these four dead writers seem to find an echo in the views of those occupying the highest political offices. Conversely, several writers, students or activists who hold or echo the views held by the murdered Dabholkar, Pansare, Kalaburgi or Lankesh are in jail, or are frowned upon by the State. Their worldview, encouraging people to demand their rights, educate themselves and others, organise and agitate, is the reason why at least 13 intellectuals, teachers and lawyers, including Dr BR Ambedkar’s grand-son in law, are in prison. Years on, the trial is yet to start on charges of wanting to bring down the Indian government. The state has signalled in the Bhima-Koregaon case that it is threatened by writers, intellectuals and lawyers.

Each of these four writers murdered in the past nine years encouraged large-heartedness and a wide embrace of plurality of thought and people. That they died for thinking, saying and writing what they did must worry us a lot more than it does currently. That the state does not find it compelling to bring the killers to book should be a red alert.

These writers who have been killed shared other things in common: they urged citizens to be demanding of their rights, defied socially enforced narrow boundaries, norms and beliefs and wanted people to be better versions of themselves. They paid for it with their lives. The Republic of Reason, Selected Writings of Dabholkar, Pansare, Kalaburgi, Lankesh provides a snapshot of the works of each, translated from Marathi and Kannada. Scientist Jayant Narlikar in its opening essay writes:

“Progress in society occurs when a scientific outlook prevails over innate conservatism. I am shocked at the attacks on those who have advocated rationalism and other incidents across the country in recent months.”

Extremism Everywhere

In each of their murders lie many clues about the kind of India we are living in. It is one of diminishing levels of tolerance in society at large. Perhaps fuelled by a state that is not keen on offering protection to anybody who holds views that are not in sync with its plans.

Most recently, the Kannada writer, Devanuru Mahadeva, a winner of the State and Central Sahitya Academy awards, has written a book calling out the RSS as an organisation that supports the Chaturvarna and about Dalits, minorities, women and the Bahujan (together comprising about 90% of India), outlining how they have benefited from the Constitution, which is now being subverted.

This has angered the Sangh. Mahadeva has also coincidentally received threats from an organisation calling itself ‘Sahishnu Hindu’, which has been threatening to eliminate him and 59 other writers and activists.

From the fatwa against Rushdie to, decades later, these four murders or, indeed, the hate spewed at writers who returned their Sahitya Akademi awards protesting the treatment meted out to assassinated MM Kalaburgi’s family, extremism of this nature is just two sides of the same coin. It is like the famous coin in the film Sholay, which had the exact same thing on both sides.

When Writers Have the Last Word

The current government would have been happy to highlight the ‘extremist’ nature of Islam and jump at an opportunity to present the Rushdie affair as an exhibit. Sadly, for them, Rushdie has taken away the ability of anyone to make Hindutva-friendly noises about his own case. As he wrote for Pen America’s special anthology for India’s 75th Independence Day, “Now that dream of fellowship and liberty is dead, or close to death. A shadow lies upon the country we loved so deeply. Hindustan isn’t hamara anymore. The Ruling Ring – one might say – has been forged in the fire of an Indian Mount Doom.”

This paragraph alone seems to have left the government of India tongue-tied. Writers cannot win elections (though Vaclav Havel did) or receive electoral bonds, but they can often end up having the last word, and that packs in more punch than is immediately evident. Rushdie’s ability to see religious extremism, irrespective of the colour of the robe donned by godmen, lends clarity to our times. And as Narendra Dabholkar’s son, Dr Hamid Dabholkar, told me recently, “During these dark times, when fundamentalist forces from both sides are feeding into each other, it’s very important for tolerant, humanitarian streams of religion and rationalist forces to join hands to fight this battle.”

(Seema Chishti is a writer and journalist based in Delhi. Over her decades-long career, she’s been associated with organisations like BBC and The Indian Express. She tweets @seemay. This is an opinion article and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)