As per the recent statistics released by the PRS legislative research team, the Monsoon Parliamentary Session of 2023, held from 20 July 2023, to 11 August 2023, functioned for 43% of its scheduled time, while the Rajya Sabha functioned for 55%. Despite a short period of time, 23 Bills were passed during this session, which also saw the first no-confidence motion of the 17th Lok Sabha.

The Session saw higher legislative activity amidst a rail-roading of Bills introduced and passed. 56% of Bills introduced were passed with little scrutiny by both Houses (where a bill on average passed within eight days of introduction). See the figures below for reference.

According to PRS Legislative, “Lok Sabha passed 22 Bills in this session. 20 of these Bills were discussed for less than an hour before passing. Nine Bills, including the IIM (Amendment) Bill, 2023, and the Inter-Services Organisation Bill 2023, were passed within 20 minutes in Lok Sabha.

The Bills to create the National Nursing and Midwifery Commission and the National Dental Commission were discussed and passed together in Lok Sabha within three minutes. The CGST and IGST amendment Bills were passed together within two minutes in Lok Sabha.”

Rajya Sabha passed 10 Bills within three days. When some opposition members walked out of the upper house, the Bills were passed in their absence.

Bills expanding the discretionary powers of the LG in Delhi, allowing for the mining of strategic minerals like lithium, and regulating personal data were passed by Parliament within seven days of introduction. The Anusandhan National Research Foundation Bill, 2023 was passed within five days of introduction.

Regression in Parliamentary Discourse, Critique and Reflection

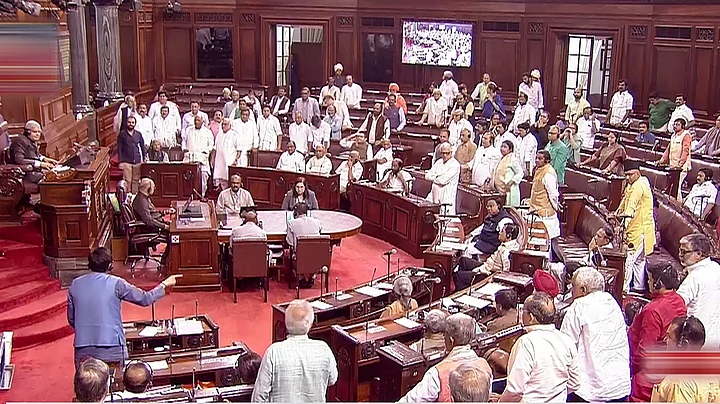

Waves of parliamentary theatrics have now defined the disjointed operative functionalities of Indian democracy over the last few years. For watchers and observers of each parliamentary session’s proceedings, repetitive acts of adjournments, an ecosystem of chaos, red flags/protests (in and outside the chambers of the house), bias and favoritism in attitudinal modulations of House speakers (against opposition party parliamentarians), have all become a part of an unusual norm, defining/catalyzing a speedy passing of Bills by the ruling executive, without critical discussion, or appropriate reflection.

On 10 August, for example, amidst an uproar, the Rajya Sabha Speaker, Jagdeep Dhankar, passed the Pharmacy (Amendment) Bill in a matter of three minutes, from the time it was called for a vote call, without the ‘Aye’ (‘Yes’) vote of the House parliamentarians (what one can hear is a loud ‘No’ when the vote was called).

One can also read the details of the newly introduced Election Commissioners Bill despite what the Supreme Court held earlier this year. The SC was then examining Article 324(2) of the Constitution. It says that the appointment of the Chief Election Commissioner and ECs shall "subject to the provisions of any law made on that behalf by Parliament, be made by the President."

In legal scholar Gautam Bhatia’s constitutional and jurisprudential interpretation (see here) of the SC judgment, “The SC did not say that the CJI has to be on the appointments committee under the future law. Thus, the mere fact that the new bill removes the CJI is not the reason why it's bad. But nor did SC say that *any* law would be consistent with the constitution. The law would have to ensure that the EC was adequately insulated from executive dominance because the referee has to be impartial. The Election Commissioners Bill obviously fails that test.”

There is an insidious way in which the current regime has used the legislative and other institutionalized apparatus to further its agenda of establishing centralized, consolidated, absolutist control. The presence of legal voids (say from recent or previous SC judgments), and state-power, amidst a weaker opposition, makes its path less embroiled with challenges. That’s even more troubling.

The 3 Highlights of the Session

This Monsoon session, as an observer, saw three highlights, signaling a crisis (in transitioning permanence) of accountability, an overcentralized executive action (under institutional capture), just in the way different bills were passed and issues in them were ignorantly dismissed. The three highlights are:

The chaos around the growing ethnic conflict in Manipur

The passing of the Digital Personal Data Protection Bill, 2023

The passing of the Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi (Amendment) Bill, 2023

The ongoing conflict in Manipur should have perhaps taken center stage this Monsoon session in allowing the union government to address questions of its own accountability while discussing key concerns of the state of governance in a BJP-governed state, where an environment of uninterrupted violence has evoked nation-wide criticism of the Biren Singh government.

The Centre for New Economics Studies has been engaged in providing a more detailed discussion on the conflict issues around state apathy, difficulties for organisations providing relief, and the Conflict’s multifaceted economic impact on the state of Manipur and the northeast (see here for more).

If one looks at the data on question hour sessions, only 9% of questions listed for oral responses were answered in Lok Sabha, and 28% in Rajya Sabha. Very little discussion followed on the nature of concerns shared by the opposition on the ethnic violence unleashed in the state of Manipur.

While reflecting on the selective interpretation of events and the way the proceedings happened, as they transpired this Monsson session (as a pattern seen for some time now), one can only reminisce how in the current governmentality, there are elements similar to that of the Raj, the colonial British administration, that ruled India for over two centuries (first by Company and then by the Queen’s rule), establishing an imperial umbrella- centralizing, consolidating power via law, language and knowledge.

A systematic capture of institutions, seen amidst a deep retrogression in democratic values, and constitutionally safeguarded separation of powers, one may only ascertain how the current state of polity in India closely resembles the lived experience of a colonial administration, consumed by its anxieties, insecurities, and controlling-nature to rule-govern and patronize at all costs sans accountability, or regard for constitutionalism.

(Deepanshu Mohan is a Professor of Economics and Director, Centre for New Economics Studies (CNES), Jindal School of Liberal Arts and Humanities, O.P. Jindal Global University. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)