Dunya hum ko abhi nahi gardaane gi

Aane vaali nasl magar pehchaane gi

(Just now the world does not think us worthy of consideration

But we will be recognized by the future generation)

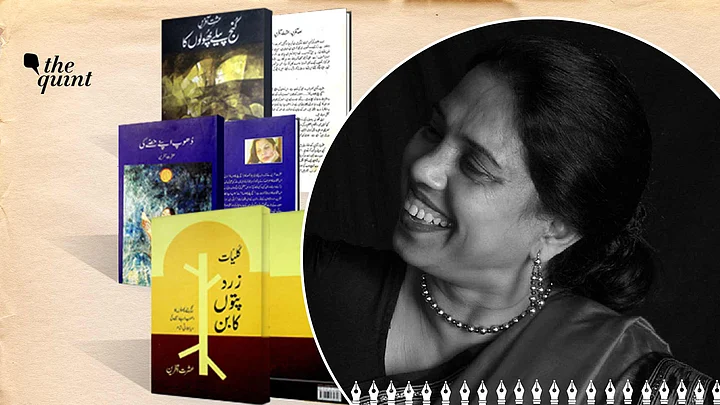

Ishrat Afreen, born in 1956, moved from Pakistan to India and then to the US, and retired from teaching at the University of Texas. She has her own official website and has been publishing her poems since she was 15. In fact, earlier last year, on 30 April, she reached a unique milestone among her contemporary poets who were born in the 1950s: the golden jubilee of her poetic career, a distinction which is hers alone. Three of her collections have been published, one in the 1980s, Kunj Peele Phoolon Ka (The Grove of Yellow Flowers) and two, more recently, in 2005 and 2017 – Dhoop Apne Hisse Ki (My Share of Sunlight) and Diya Jalaati Shaam (Lamp-lit Evening). All her existing collections of poetry were published as Zard Patton ka Ban (The Forest of Yellow Leaves) in 2017. One can watch her perform her poetry in the public domain. As I write these lines, she is giving final touches to her new poetic work, Parinde Chahchahate Hain (The Birds Are Chirping). Her poems published in Rukhsana Ahmed’s anthology, Beyond Belief: Contemporary Feminist Urdu Poetry (1990), deployed a rawness that consciously gendered the poetic experience.

'The Mother Had Won': Ishrat Afreen's Women

One of my favourites among her poems is Intesaab (Dedication) for its ‘take-no-prisoners’ attitude and its direct evocativeness.

Mera qad

Mere baap se ooncha nikla

Aur meri maa jeet gayi

(I grew taller than my father.

My mother had won.)

The second poem, Gulaab aur Kapaas (Roses and Cotton), positions her more in the tradition of progressive writers, especially Makhdoom, who sought to see beauty in labour and valued women’s labour through traditional invocations of beauty.

Afreen takes the metaphors much further, though, positioning them directly against the ephemeral concept of beauty associated with privilege.

Kheton mein kaam karti hui ladkiyaan

Jeth ki champai dhoop ne

Jin ka sona badan

Surmayi kar diya

Jin ko raaton mein os aur paale kaa bistar mile

Din ko sooraj saron par jale

Ye hare lawn mein

Sang-e marmar ke benchon pe baithi hui

Un haseen mooraton se kahin khoobsoorat

Kahin mukhtalif

Jin ke joode mein joohi ki kaliyan sajee

Jo gulaab aur bele ki khushboo liye

Aur rangon ki hiddat se paagal phiren

Khet mein dhoop chunti hui ladkiyaan bhi

Nai umr ki sabz dehleez par hain magar

Aaina tak nahin dekhteen

Ye gulaab aur dezi ki hiddat se naa-aashna

Khushboo-on ke javan-lams se bekhabar

Phool chunti hain lekin pahanti nahin

In ke malboos mein

Tez sarson ke phoolon ki baas

Un ki aankhon mein roshan kapaas

(These girls who toil in the fields

Whose golden skin has been dyed dark by the sun

Who sleep on beds of frost and dew at night

And are burned by the sun during the day.

They are much prettier than those statues

Sitting on marble benches

On green lawns

Prettier and more different

Than those whose tresses are adorned with roses and

jasmine buds

And who run wild in a sharp profusion of colours.

The girls who pluck sunlight in the farms

Are also at the green threshold of the new era, but

Do not even look at mirrors

They are unfamiliar with the sharpness of rose and

juhi

They pluck flowers, but do not wear them

Their clothes carry the pungent scent

Of mustard flowers instead

And their eyes the brightness of cotton.)

'This Cruel Girl': An Introduction

This is how she introduces herself for the uninitiated, in her poem Mein (Me):

Yeh anaa ke qabile ki

Saffaak larki

Teri dastaras se

Bohat door hai

(This cruel girl

From the tribe of ego

Is very far

From your reach.)

Then, in another short poem Aadam ki Maa (Adam’s Mother) she sums up the dilemma of Aqleema, Cain’s sister, who according to some versions of the Biblical/Islamic tale, had desired her for himself although she was forbidden to him.

Havva

Aadam ki zauja

Aur__ Aqleema?

(Eve

Wife of Adam

And__ Aqleema?)

Aqleema, who was denied a voice in deciding her own fate, finds a kindred sister in Ishrat Afreen who herself ends her maiden collection Kunj Peele Phoolon Ka on the couplet:

Yeh chand haroof bhi ik umar ki kamaai hain

Ke ghurbaten hi viraasat mein hum ne paayi hain

(These few words too are the earnings of a lifetime

In that poverties are very much what we have obtained in inheritance.)

'Mother, You are Such a Liar!'

Being a woman in a patriarchal society also means confronting – and conveying – rude truths from one generation to another, as Ishrat Afreen narrates in her poem Aik Sach (A Truth):

Khavateen ke aalmi din par

Main ne apni beti ko

Apni taaza nazm suna kar

Daad-talab nazron se dekha

Is pal

Is ki aankhen

Aisi tanz bhari muskaan liye theen

Jese mujh se kehti hon

Maan tum kitni jhooti ho!

(On the International Day of Women

I, reading out my new poem to my daughter

Looked at her desiring appreciation

That moment

Her eyes

Carried such a taunting smile

As if saying to me

Mother you are such a liar!)

Ishrat Afreen on Being Young

It seems pertinent to re-read Ishrat Afreen’s recent poem Saalgira (Birthday) given her own 65th birthday recently on 25 December:

Main sochti hoon ab se pehle

Jin ko ginti kam aati thi

Voh kitne maze mein rehte the.

Jo bacchon ki pedaish ko

Baadh aur vabaa ke saalon se jora karte.

Tab basti mein

Jab tak ik boodha rehta tha

Basti ke baaqi log toh bacche hi kehlaate the

Ab saalon aur maheenon ki is ginti ne

Hum ko boodha kar daala hai.

(I think in times past

Those who were weak in counting

Used to have quite a blast.

Who used to link the birth of children

With the years of flood and contagion.

Then, in the village

Until there lived a man of old age

The remaining people of the village were known as children

Now this counting of years and months

Has made us into old women.)

East Pakistan and a Poet's Identity Crisis

When I called Ishrat Afreen sahiba just last month on 16 December to share with her our mutual anguish on the 50th anniversary of the separation of then-East Pakistan and the independence of Bangladesh, she did not offer me a poem on the event itself, but a fresh trauma of a creative soul who has not been able to accept her adopted country as her home, partly because her current home does not give her the recognition she so richly deserves.

Ironically, it was also the events of 16 December 1971 that deepened the crisis of identity in Pakistan, since the very basis of the ‘Islamic’ identity of the country born in 1947 was ruptured.

In my humble opinion, the identity crisis of the poet becomes at one with the identity crisis of her native country in her latest poem Shanakht (Identity):

Mujh ko koi nahi jaanta hai yahan

Log mujhe kehte hain

Kya aap bhi shayiri karti hain

Acha! Kya likhti hain

Aapko to kabhi hum ne dekha nahi

Aap ke shauhar-e-naamdaar

Shehr saara inhen jaanta hai

Kaun desi hai is shehr mein

Jis ne in se khareedi na ho aik kaar.

Main bhi hans deti hoon

Hum jo hain tees barson se is shahr mein

Saath jaate hain bazaar toh

Log karte hain in ko lapak kar salaam

Mujh ko koi nahi jaanta hai yahan.

Jab main vatan laut ke jaati hoon

Kya pazeeraai hoti hai meri vahan

Sochti hoon yaheen bas rahoon

Roz interview karte hain aa-aake log

Lekin is mein bhi diqqat ye hai

Log karte hain mushkil savaal

Qaumi aizaaz koi mila aapko?

Aap ki ghazlen

Kitne gulukaaron ne gaayi hain?

Sakh mayoos hote hain voh

Sun ke mera javaab.

Ho gaye sher kehte mujhe

Saal poore pachaas

Aur yahaan bhi hai ye mera haal

Koi mujh ko nahin jaanta.

(Nobody knows me here

People say

Do you also write poetry

Really! What do you write

We have never seen you

Your husband is a celebrity

He is known to the whole city

There is not a desi in this city

Who has not bought a car from him.

I, too, smile spontaneously

We who have been for thirty years in this city

When we go together to the bazaar

People hurriedly greet him

Nobody knows me here.

When I return to my native country

How I am welcomed there tremendously

I think about settling here permanently

People arrive in droves to interview me relentlessly

But there, too, is this difficulty

That people do not inquire delicately

Have you gotten any national honours?

Your ghazals

Have been sung by how many performers?

They get very disappointed

Hearing my response.

It’s my golden jubilee

Of versifying triumphantly

And here too is my situation

Nobody knows me.)

A Pakistan From Another Time

There is no space here for a detailed discussion on her trilogy of epoch-making longer poems, which are part of her second volume, Dhoop Apne Hisse Ki, and which the poet herself describes as significant to the evolution of her critical consciousness.

These are Mazaafaat (Suburbs), Jahanzaad and Yeh Basti Meri Basti Hai (This Settlement is My Settlement), which present a dirge for the experiences of rural anomie, women empowerment and urban bonhomie; they are nothing short of micro-histories of a Pakistan from another time that we seem to have lost as we descend towards intolerance, patriarchy and paranoia.

In completing the golden jubilee of a remarkable career that spans whole cultures and continents, Ishrat Afreen remarkably and uniquely combines the classicism of her predecessors like Ada Jafri and Zehra Nigah, and the more conscious feminists like Fahmida Riaz and Kishwar Naheed. This combination is rare among her contemporaries. She is also the sole torchbearer of the much-vaunted Ganga-Jamuni civilisation as she is of the rebellious ethos of the Progressive Writers Movement in our own time. Her aforementioned poem on identity modestly camouflages the fact that in her own country of origin, she remains forgotten and neglected.

No national honours have indeed been bestowed on her nor have her works been widely translated or critically analysed for a younger generation.

It was this invisibility and short-sightedness that the late Fahmida Riaz lamented in her foreword to Ishrat Afreen’s second collection of poetry when she wrote:

“…Would this unparalleled poetry be able to find a discerning reader? Unfortunately, mediocrity has totally dominated Urdu literature for a long time. True poets (and Ishrat is very much a poetess) have been ejected from the ranks of popular poets. Only traditional, decorative and social poets are very much being preferred.”

The Age of Ishrat Afreen

However, Ishrat Afreen’s poetic legacy is secure. Her own name means the creator of joy but her heart continues to bleed for the concerns of the underprivileged, be they in the United States, India, her native Pakistan, or any part of the world. For the last 50 years, she has been a leading female Urdu poet of her generation and is a national honour and institution unto herself. We are very much living in the age of Ishrat Afreen.

Apni chador ko parcham kar sakti hai

Aurat ik tareekh raqam kar sakti hai

(From her chador a flag she can make

A whole history can a woman narrate)

(All translations from Urdu are by the writer. Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently based in Lahore, where he is also the President of the Progressive Writers Association. He is currently working on a book ‘Sahir Ludhianvi’s Lahore, Lahore’s Sahir Ludhianvi’, forthcoming in 2022. He can be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for the same.)