Look at it this way.

It was definitely not the most iconic romantic movie to tumble out of Bollywood by any yardstick. There are perhaps dozens of movies where the “chemistry” between the protagonists has outclassed and out-sizzled the two in this one.

It is definitely not a movie whose music and songs would venture anywhere near inspiring greatness. Hummable yes, but that’s about it.

There was some decent acting no doubt. But the performances would struggle to make it into even the top 25 acting master classes. There was nothing new in the plot. It was as Punjabi kitsch as Bollywood movies have been for decades.

There was humour and fun some well doled out doses. In terms of breaking box office records, it is nowhere near the all-time blockbusters.

And yet, it enthralled young Indians into paroxysms of frenzy. The energy and enthusiasm in movie theatres were simply scintillating.

28 years after it was released to a rapturous welcome, the movie is still being screened at Maratha Mandir in Mumbai. This year too, faithful and loyal fans made the pilgrimage to pay homage to Raj and Simran.

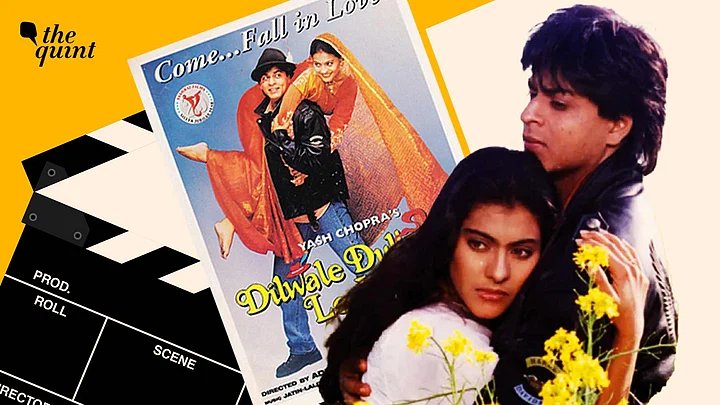

Yes, we are talking about Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge (DDLJ) which was released on 20 October 1995. There have been numerous better movies, even if one considers the subjective manner in which critics and audiences rate a film.

Then what has made DDLJ such a phenomenon?

Reflecting the Aspirations of Post-liberalisation Indians

Actually, the manner in which the movie was received was an election of a different kind, of an India that was emerging after the stifling socialist controls that caged Indian dreams and entrepreneurs were dismantled in 1991. This was an India that was embracing globalisation as eagerly as Raj Kapoor had embraced Nargis in Shri 420, Rajesh Khanna had embraced Sharmila Tagore in Aradhana or Amir Khan had embraced Juhi Chawla in Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak.

The Indian diaspora has been around in England for ages; since before the British relinquished Imperial power in 1947 and went home. Movies have been made about the diaspora even earlier. But the protagonist Raj (Shah Rukh Khan) was an entirely different breed compared to earlier versions. Those who have watched actor Manoj Kumar singing paeans to India apart from maudlin Mukesh songs in Purab Aur Pashchim would know the difference. The protagonist played by Manoj Kumar would have found it impossible to even comprehend playing Rugby and the guitar as he serenaded his lady love across Europe the way Shah Rukh Khan did with Simran (Kajol).

In a sense, the DDLJ protagonist reflects the dreams and aspirations of post liberalisation Indians. For decades after independence, economic conditions simply did not allow the emergence of a bona fide middle class. With GDP growing on an average of about 3 percent a year and population expanding at the same rate, India remained almost as poor in 1980 as it was in 1947. In fact, the actual number of Indians living in absolute and abject poverty was far higher in 1980 than in 1947.

The few who could claim middle-class status had to wait seven years for a landline phone connection and about five years to purchase a two-wheeler after paying for it. The limited few who could afford a car had to choose between obsolete models of the Ambassador or Premier Padmini. The luckier ones would have benevolent relatives or friends living abroad to come to India with some “global” brands.

As mentioned in a previous column in this series in April 2023, a new India finally began to emerge in 1982 with the advent of the colour TV, Japanese motorcycles, the Maruti car, and a few other products and services. But India had a closed economy till 1991. As a matter of fact, the number of Indians living below the poverty line in 1991 was multiple times that in 1947. It is 1991 that opened the floodgates.

Swiss Tourism: Symbolic of a Change in Mindset

People of a certain generation like the co-author were already in college when the Yash Chopra movie Silsila was released. The movie may not have done wonders at the box office but the breathtaking beauty of locales in Europe including miles and miles of tulips on offer when Amitabh Bachchan was serenading Ekta was something to behold.

For even middle-class Indians of that era, a trip to Europe was out of the question. They enjoyed their European holidays vicariously by watching movies like Silsila. By the time Yash Chopra’s son Aditya made DDLJ, upper-middle-class Indians had started living their European dreams. DDLJ was elected with astonishingly beautiful scenes from across European countries.

The Jungfrau region of Switzerland was so lovingly portrayed in the movie that tens of thousands of Indians have gone there as tourists after watching DDLJ. A grateful Swiss Tourism has repeatedly rewarded Yash and Aditya Chopra for making a movie that has inspired many Indian tourists to visit Switzerland. Even in February 2023, Swiss Tourism organised an event in the country to honour the memory of the late Yash Chopra. Today, droves of Indian tourists in Switzerland are greeted with prominent signages in Hindi, Punjabi, and Gujarati. It is estimated that more than 30,000 Indians go to Switzerland every year as tourists.

Some discerning folks would not have noticed one more thing. DDLJ was leased a few weeks after mobile phone services were launched in India. Today, it is impossible to imagine life without the ubiquitous mobile phone. Yet, for years even after launch, a majority of Indians could not afford to use a mobile phone.

It took a decade after the release of DDLJ for mobile phones to be a part of mass consumption. An even bigger change in attitudes and mindset of Indians that DDLJ projected was the manner in which they viewed rich and successful people, mostly businessmen or entrepreneurs. Thanks to Mahatma Gandhi’s fondness for asceticism, frugality, and even poverty and the legacy of Nehruvian socialism, it had become fashionable to consider being poor as a badge of some strange kind of honour. It was good to be poor.

As a corollary, it was sinful to be rich. Most Indians treated (many still do) rich business people as some kind of perfidious villains whose sole purpose in life was to exploit the poor. This was reflected in the galaxy of successful movies that portrayed the rich as unrepentant villains and rogues. Perhaps Dhirubhai Ambani was the first entrepreneur to catch the eye of middle-class and aspirational India in a positive way. But it was only in the 1990s, after the liberalisation of India that attitudes started changing rapidly.

The advent of 24-hour satellite television in 1992 resurrected the long-buried dreams of middle-class Indians to chase wealth as a legitimate purpose of life. Movies like Hum Aapke Hain Kaun had already told the story that rich Indians could be good people. DDLJ took it to another level in an effortless manner. Today, successful entrepreneurs and promotors of start-ups that have become Unicorns have become role models for Indian youth.

As India moves towards a $5 trillion economy, this will gather momentum. No doubt, India is still confronted with deep and desperate poverty in many pockets. But barring the very few, even the poor have acquired materialistic aspirations. What’s wrong with that unless you are an activist whose career is dedicated to peddling poverty as the default mode for Indians?

It Became Cool to Be Rich

DDLJ showcased yet another related trend. For decades, Indians were blue-collar professionals in foreign countries except for a small percentage in the US and the UK who were doctors and engineers. But that has dramatically changed in this century.

DDLJ provided a glimpse of that change. Remember how Amrish Puri, Simran’s dad was proud of working extremely hard to become successful? And how he talks of planning to invest in a beer distillery in Punjab for his prospective son-in-law?

One big diaspora name around the time DDLJ was released was Sameer Bhatia who created Hotmail and sold it to Microsoft for $ 500 million. Today, there are hundreds of such diaspora success stories. For instance, in 2022, Sundar Pichai of Google and Alphabet earned a “salary” of $226 million, or about Rs 1,500 crores!

DDLJ did yet another thing that holds good even in contemporary times. It made being rich cool. It showcased how the diaspora Indians had achieved immense success through sheer grit and hard work. And yet, it showed even such successful folks as rooted in Indian traditions.

Simran’s father is incensed when he learns about her love for Raj. He promptly takes her back to Punjab in India to get her mailed off to the son of his long-lost village pal. Raj chases them all the way to India in an effort to seek the blessings of her father. He refuses to run away with Simran. In hindsight, it does appear to be a classic case of regressive patriarchy. But then, like it or not, that is India.

Today, the same India relishes movies like Kantara that celebrate rooted Indian traditions. Many Indians at the same time relish flesh, sex, dhoka on OTT platforms.

Take your pick.

(Yashwant Deshmukh & Sutanu Guru work with CVoter Foundation. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)