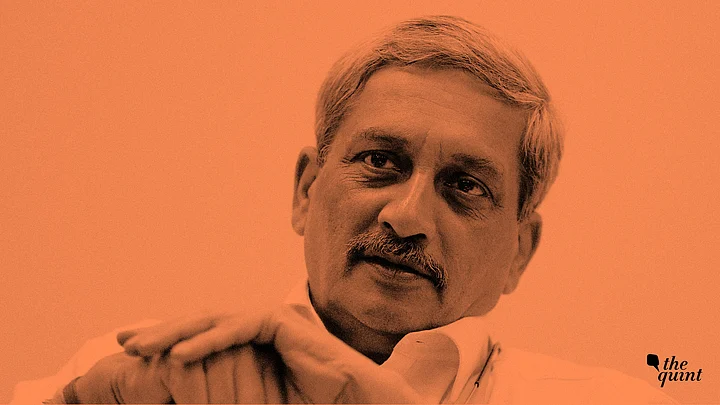

(On late Manohar Parrikar’s first death anniversary, The Quint is publishing this piece from its archives about his time as Goa chief minister and minister of defence. Originally published on 18 March 2019.)

Manohar Parrikar, who passed away on Sunday evening after a valiant battle against cancer for a year, was unlike many of his colleagues in Bharatiya Janata Party. He was not the archetypal Sanghi who spouted Hindu nationalism by the hour or wore saffron on his sleeve, yet Parrikar’s devotion to the ideals and agenda of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) was second to none.

Parrikar was Goa’s chief minister for the fourth time since 2017. He held an edgy government together by the sheer dint of his personality as India’s defence minister from 2014 to 2017 before he chose to return to his tiny home state.

The Marathi school boy from Mapusa town who made it to the hallowed campus of IIT-Bombay and graduated with B.Tech (Metallurgy) in 1978, Parrikar was the country’s first chief minister with that exalted qualification.

Too busy to read? Listen to this instead.

He was also a rare one to walk into a state Assembly in an advanced stage of pancreatic cancer with a pipe streaming into his nose.

Bringing Stability to Goa

Did he work and fulfil his public commitment of his free will or was he compelled to follow the bidding of his party? The answer lies in the political chaos in the state since his demise – the BJP unable to decide on his successor, regional allies of the party staking their claim, and the Congress finally raising its hand to be counted as the single largest party. As long as Parrikar breathed, he ensured that Goa would have a BJP government.

He could not have done it without indomitable will power, a steely determination, and the drive to get the task done.

His amiable charm, the honest – not cultivated or faux – simplicity of half-sleeved shirts and chappals, his accented English and deep knowledge of his subjects, his nod to Goa’s multi-religiosity and multi-culturalism, all these helped too.

When in Delhi, he missed his fish-and-rice and Goa’s susegad – relaxed attitude enjoying life to the fullest.

Parrikar is credited with helming steady governments in Goa otherwise known for its unstable political formations and frequent cross-overs of MLAs from one party to another making governments vulnerable. He is also credited with a number of infrastructure projects across Goa, industrialising the state known for its laid-back attitude, starting and firmly placing the International Film Festival of India (IFFI) on the world’s film calendar, exposing the multi-crore mining scam in 2010-11, among other things.

Poster-boy of Technocrat Hindutva

Beneath it all lay the quintessential core of the RSS philosophy. He was the technocrat Sanghi long before the type came into its own. Parrikar acknowledged that it taught him discipline and commitment to nationalism. He paid back the debt in full measure – and more – by assiduously expanding the organisation’s ideological footprint in a state with 27% Christians and nearly 9% Muslims. The popularity of the BJP in Goa, the staggering increase in its membership even pre-2014, the emergence of ultra-radical Hindutva outfits all coincide with Parrikar’s political career.

Parrikar was introduced to the RSS while still in school. When he was preparing for the IIT, he had been made Mukhya Shikshak in Mapusa. He headed a unit of the RSS in the IIT.

In 1979-80, when he returned to Goa and set up his engineering-oriented business, he resumed the organisation’s work. By the mid-80s he had been appointed Sanghchalak for north Goa. The state has two Lok Sabha and 40 Assembly seats.

Parrikar drew on the Ram Janmabhoomi movement to deepen the RSS in a state which had not yet warmed up to the ideology. In the mid-90s he was deputed to the BJP with the explicit aim of cutting the regional Maharashtrawadi Gomantak Party (MGP) down to size. Parrikar’s strategic plans and ceaseless work saw the BJP emerge as the alternative to the Congress. The amalgamation of the Hindutva vote had yielded the desired results. Parrikar headed the first BJP government in October 2000.

Rise of Militant Hindu Organisations in Goa

During the years when Parrikar occupied the CM’s chair, Goa saw the rise of militant Hindu organisations which played a crucial role in the gradual radicalisation in the Maharashtra-Goa-Karnataka belt. Back in 2001, the Parrikar government handed over 51 government primary schools to Vidya Bharati, the RSS-affiliate.

The Sanatan Sanstha, whose activists are allegedly involved in assassinating rationalists including Dr Narendra Dabholkar and journalist Gauri Lankesh, was founded here in 1999 and is headquartered in Ponda.

Its activists Malgonda Patil and Yogesh Naik died while reportedly ferrying a bomb to be planted in a Margao church in 2009.

The Hindu Summit was held in Goa in 2012. It led to the setting up of the Hindu Vidhidnya Parishad which wants to establish law “formulated (by) science of spirituality embedded in Sanatan Hindu Dharma” instead of the Constitution of India. Goa’s capital Panaji was the venue for the BJP’s national executive in April 2002, less than two months after the horrific train burning at Godhra and the massacre of Muslims. Parrikar was in complete command.

Paving the Way for Modi’s Rise

It was here that Narendra Modi, then the beleaguered chief minister of Gujarat under fire for his mishandling of the post-Godhra massacre, got a reprieve – in fact a pat – from his party. The next day, Vajpayee spoke at the Panaji ground, “…Who lit the fire? How did the fire spread?...Wherever Muslims live, they don’t like to live in co-existence with others”. Parrikar’s counsel had been sought for how the Goa crowd would receive this sentiment. He gave his thumbs-up. “It was my big moment, I’ve staked it all,” he told me later.

In 2013, it was Parrikar who proposed Modi’s name to be the BJP’s campaign chief for the Lok Sabha election the following year. It paved the way for Modi to emerge as the party’s prime ministerial candidate.

Yet, the saffronised Goa is unlike other states in the same basket; its unique multi-ethnic and multi-religious mix demands that all politics makes allowance for others. For pragmatic reasons, Parrikar reached out to the Church ahead of the last few elections. Seven of the BJP’s 14 legislators are Christians.

Encouraging Hindutva Nationalism – With a Smile

As India’s defence minister, his grasp and non-nonsense attitude earned Parrikar praise in Delhi. He could be at home with jawans as well as the generals, they said. Goa cheered him for one of their own occupied such an important chair in the country’s council of ministers. If he was upset at being ignored during the Rafale negotiations which Prime Minister Modi headed while in France, he preferred to not show it. Instead, he returned to Goa as chief minister – working in Panaji, living in his family home in Mapusa till cancer struck.

There is no doubt that Parrikar changed the narrative and direction of Goa’s politics – from provincial and secular to national and radical, from personalities to issues, from self-determining and chaotic to part of the national discourse.

It was easy to like him and his techno-solutions approach to politics which he understood as a means of public service. Yet, he was the man who said of actor Aamir Khan during the debate on intolerance, “If anyone speaks like this, he has to be taught a lesson of his life”.

Parrikar nurtured a deep commitment to Goa, its progress and its unique character. In parallel, he also cultivated and encouraged Hindutva nationalism – albeit with a smile.

(Smruti Koppikar, Mumbai-based independent journalist and editor, has reported on politics, gender and development for nearly three decades for national publications. She tweets @smrutibombay. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)