On the night of 11 July 2004, a 32-year-old woman was taken from her home in Laipharok Maring in Manipur, 20 km from Imphal, by members of the 17th Assam Rifles. The next morning, her body was found mutilated and with 16 bullet wounds. She had been stripped, allegedly raped, and murdered.

Assam Rifles claimed that she had been picked up as she was part of the People's Liberation Army (PLA), a militant outfit in Manipur that had often targeted the Army and security forces. They alleged that she had been a PLA militant since 1995 and was an IED expert.

The soldiers of Assam Rifles were able to act in this manner because of the draconian Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), which was then in force in Manipur. The Act empowered the Indian Army to arrest without warrant, to shoot and kill on suspicion, and to confiscate and destroy property in 'disturbed areas'.

It also gave Army personnel almost full immunity from the law. The result was complete unaccountability. It led to multiple incidents of alleged human rights abuses, including the horrific case of the said woman.

Not Much Has Changed in Manipur When It Comes to Sexual Crimes

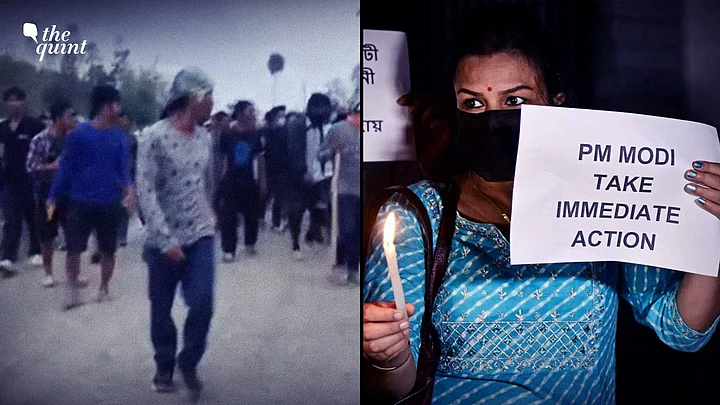

Fast forward to 2023, nothing much has changed in Manipur. Yet again, sexual violence has played out with impunity. Yet again, women have been targeted with the aim of 'intimidating' the other side, with the aim of 'dishonoring' the other side.

Yet again, it is clear that no action was taken despite clear knowledge of the crime on the part of the police and the state government. It is only the surfacing of a viral video that has prompted action, in response to massive outrage. Surely, this is not how the law needs to be goaded into action.

In the 2004 case too – in pre-social media days – it took a sensational protest by Manipur's women to get the national media and the government in Delhi to take notice. On 15 July 2004, 12 middle-aged women or 'Imas' (which translates as 'mothers’ in Meitei) took off their clothes at the gate of Imphal's Kangla Fort cantonment, where Assam Rifles was then stationed.

They held up banners, partially covering their naked bodies, that said "Indian Army, Take Our Flesh." It is ironic that these 12 women were actually jailed for months after their protest.

Justice Appears To Be a Far Cry Even Today

The aftermath of the 2004 case also makes for poor reading. The then Manipur government set up a one-man Inquiry Commission to look into the woman's death, assigning a retired judge, Chungkham Upendra Singh, for the job.

Assam Rifles refused to send anyone to give statements or testify before Justice Upendra Singh and even appealed against the legitimacy of the inquiry. In what seems like closing of ranks, the Guwahati High Court ruled that the Manipur government had no authority to set up an Inquiry Commission. It also suppressed the contents of the Commission's report.

It was only in 2014, when the Supreme Court received Justice Singh's report as part of a larger case on custodial violence, that the findings finally emerged. Justice Singh concluded in his report that the woman had been brutally raped and murdered.

So now, in 2023, what will it take for justice to be served in the case of three Kuki women being assaulted, stripped, and paraded in public?

Not that it should matter, but since we have often been guilty of treating our fellow Indians from the northeast as second-class citizens, it is worth reminding that the oldest of the survivors is reportedly the wife of a Kargil War veteran.

And the youngest survivor has alleged that her father and brother were killed by the same mob that assaulted and stripped her. So the charges here are grave – ranging from murder to gang rape.

Irom Sharmila's Protests Did Little To Deter Gender-based Crimes

The pessimism about the meting out of justice comes from years of disappointment, especially in Manipur. Let's rewind to November 2000, when Irom Sharmila began her 16-year fast against AFSPA.

The trigger for her fast was the infamous Malom killings that took place on 2 November 2000. Ten civilians were shot and killed at a bus stand at Malom, a village near the Imphal airport. It was alleged to be a fake encounter while the soldiers of the 8th Assam Rifles, allegedly responsible for the killings, claimed that they had retaliated when their convoy came under fire.

Protected by AFSPA, no soldiers were prosecuted. Among those killed were Laisangbam Ibetombi, a 62-year-old woman, and 18-year-old Sinam Chandramani, who had won a National Bravery Award just two years earlier in 1998. It took 14 years for the Manipur High Court to order compensation of Rs 5 lakh for each of the families of the victims.

And Irom Sharmila? Even as her protest turned legendary, with local residents calling her the 'Iron Woman of Manipur', for the government, she remained in breach of the law. She was repeatedly re-arrested on the charge of trying to attempt suicide, was almost always in constant isolation and police custody, was consistently denied access to the media, and was force-fed nasally for 16 years.

And of course, her calls for the repealing of AFSPA went unheeded all through her fast.

Violence as an Instrument of Terror in Conflict Zones

Unfortunately, the agonising story of what the three Kuki women had to endure in early May 2023 is one among many such stories that have unfolded during the months of Meitei-Kuki violence in Manipur.

Many of them are yet to surface.

What's equally unfortunate is that it's a familiar cycle of violence, and little has been across decades to deter such crimes.

Sexual violence in conflict situations has a long history. It is an instrument of terror. It is meant to intimidate and dishonour communities, to show them who is 'in control'.

Extreme violence against the women is the surest way of doing this. It is the sworn duty of the keepers of the law, even in the 'fog' of conflict, to act robustly against the brazen perpetrators of such terrible crimes.

So far, in Manipur, that has rarely happened.