The following is an excerpt from Jawaharlal Nehru's speech from 1937, when he was the Congress party president.

“I am convinced that the only key to the solution of the world’s problems and of India’s problems lies in socialism, and when I use this word, I do so not in a vague humanitarian way but in the scientific, economic sense. Socialism is, however, something even more than an economic doctrine; it is a philosophy of life and as such also appeals to me. I see no way of ending the poverty, the vast unemployment, the degradation, and the subjection of the Indian people except through socialism. That involves vast and revolutionary changes in our political and social structure, the ending of vested interests in land and industry, as well as the feudal and autocratic Indian States system. That means the ending of private property, except in a restricted sense, and the replacement of the present profit system by a higher ideal of cooperative service. It means ultimately a change in our instincts and habits and desires. In short, it means a new civilisation, radically different from the present capitalist order.”

Fourteen years after he delivered this speech, the first prime minister of India Jawaharlal Nehru translated his dreams into reality. First came the First Amendment in June 1951 which annihilated the foundations of absolute free speech and property rights. The next month, in July 1951, Nehru announced the First Five-Year Plan. Both acts were inspired to a large extent by the Soviet Union. The reverberations of both are still being felt in contemporary India. State and central governments of all hues and ideologies are routinely arresting citizens for exercising their right to free speech. But that debate is not the focus of this column.

Here, the authors analyse the impact of five-year plans on the economic journey of India as an independent nation. On the face of it, making plans for the future should be the most sensible and wise thing to do for an individual, a family, a society, and a nation. Everyone (except the most reckless) does have some “plan” for the future. Even the mascot of Capitalism, the private sector company, or an entrepreneur makes plans for the future. Some call it vision.

To that extent, what Nehru did in July 1951 is praiseworthy. But then, there is that old cliché about the road to hell being paved with noble intentions.

Five-Year Planning: Logic and Inspiration

In hindsight, Nehru, and subsequently Indira Gandhi’s obsession with planning and five-year plans caused irretrievable damage to the Indian economy and defeated the very purpose for which they were drafted: improving the economic condition of ordinary Indians. Yet, it would be unfair to single out Nehru for this.

Large swathes of the world and people of intellect were enamoured by the promise of socialism. Bhagat Singh was actually a Marxist in many ways. Those who only disparage Nehru prop up Subhash Chandra Bose as their real hero. In reality, the concept of five-year plans was first officially recognised and put on record when Bose was the Congress president in 1938.

But what exactly were five-year plans in the Indian context?

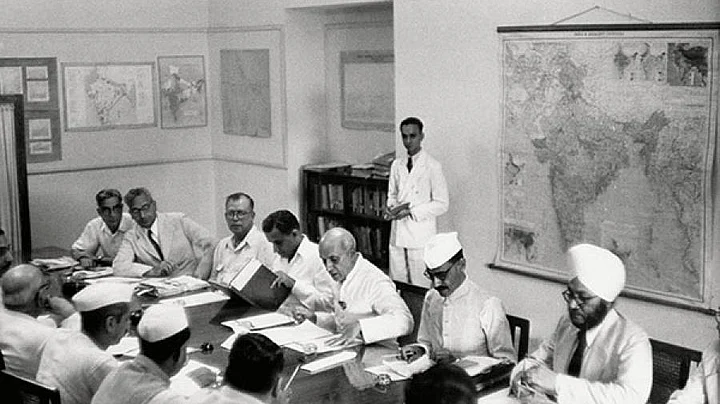

The logic was simple and elegant. A newly independent India, plundered by the British Imperial rule was desperately poor and desperately needed economic growth and development at a rapid pace. Nehru set up the Planning Commission in 1950 to suggest concrete ways in which these goals could be achieved. Since resources and capital were limited, it was felt necessary to “allocate” them in a manner that spurred growth. Thus was born the First Five-Year Plan in July 1951.

It was clearly inspired by the Soviet Union, where Joseph Stalin had introduced five-year plans in 1928. While being critical of the authoritarian excesses of Stalin, Nehru publicly admired the way Stalin had used five-year plans to transform the former Russia which was a poor, agricultural nation into a modern, industrialised, and developed economy.

In India, the first five-year plan focused on developing agriculture and irrigation since adequate food supplies were considered critical for the economy and the citizens. It is easy for contemporary critics to disparage Nehru. But he was a product of his times when “socialism” offered a tantalizing alternative to capitalism. As showcased by iconic Bollywood movies of that era, even the social narrative in the country was inspired by socialism.

Bold Initiative, but a Failure Nonetheless

Till the mid-1960s, five-year plans appeared to have been successful as the Indian economy became the most industrialised one in Asia barring Japan, and with per capita incomes higher than that of countries like South Korea, Malaysia, Indonesia, and China.

By the 1970s, as the East Asian economies raced ahead of India, supporters of “planning” insisted the economic philosophy behind it was sound. They pointed out how it is wrong to compare small countries with large ones like India and China. Till the advent of the 1980s, they gloated about how India’s per capita income was higher than that of China.

But by then, a majority of Indians were convinced there was something rotten in the system. Persistent shortages of food and virtually every consumer item that a household needs had convinced Indians that something different needed to be done. Poverty didn’t decline and unemployment remained a scourge.

By the time the 21st century arrived, it was crystal clear to all but the ideologically blind that the economic system so loving created by Nehru had failed the country and betrayed its poor citizens. By 2015, Prime Minister Narendra Modi dispensed with all the pretences, disbanded the Planning Commission, and renamed it as Niti Aayog. The last “five-year plan” was launched in 2017 and died an unsung death in 2017.

Yet, economic historians agree that the first five-year plan was a daring and bold initiative that did largely achieve its purpose. The plan had set a target GDP growth rate of 2.1% for the duration while the actual growth rate achieved was a commendable 3.6%. But it was when the first five-year plan was nearing its successful completion that Jawaharlal Nehru committed a fatal blunder. The second five-year plan was devoted to rapid industrialisation. Nothing wrong with that.

The blunder was a policy decision that coincided with the launch of the second five-year plan. It is now described by economic historians as the Industrial Policy Resolution of 1956. It reserved the “commanding heights of the Indian economy” for public-sector state-owned entities with no role whatsoever for the private sector. The lack of space prevents the authors from going into the gory details of this ill-fated document.

In brief, with this and the second five-year plan, Nehru and his advisors gave birth to what subsequently became notorious as the “license-permit” Raj. Private sector companies needed a “license” to produce anything. Delhi became a paradise for fixers who had access to politicians and bureaucrats who could approve or reject an application for a license.

Reality Upstaged Nehru's Utopia

Nehru obviously meant well; but this single folly caused incalculable harm not just to the economy, but also to the moral fibre of Indian society. Corruption became an integral and embedded part of governance. His daughter Indira Gandhi compounded the folly by imposing even more draconian state controls over private enterprise.

By the time Indians and their leaders realised how utterly destructive these stifling controls over private enterprise were, Chinese leader Deng Xiao Peng had since long introduced market and business-friendly economic policies and pronounced: it doesn’t matter what colour the cat is as long as it catches the mice.

It was only in 1991 after the Indian economy teetered on the edge of debt default and bankruptcy that industrial licensing was abolished 1991. It is to the credit of prime minister P V Narasimha Rao and finance minister Dr. Manmohan Singh that bold steps could be taken in the face of adversity could be taken.

Yet, the pernicious effects of that mindset continue to haunt India. Corruption is still rampant in all institutions of the state. You and we would be frightened to know the number of approvals that even a relatively small entrepreneur needs to open a restaurant in Delhi. And the hypocrisy continues. To take just one example: private schools are barred by law from earning profits.

So, all of them function as registered trusts and charities. But nobody is fooled as the “business” is a gold mine for those who can work around the “system”. The lead author can speak from personal experience of the trauma a first-generation entrepreneur still faces in India unless he or she has inherited at least some wealth. The barriers to entry are still formidable and achieving success on a large scale is still an uphill task, and often an impossible one.

There are exceptions of course, but they prove the rule. A growing section of Indians now celebrates and lauds successful entrepreneurs. But the rhetoric and narrative are still dominated by diatribes against “tycoons looting India”.

To quote Nehru again: “It means ultimately a change in our instincts, habits, and desires.” Human instincts, habits, and desires have outlived many a visionary dreamer. Nehru was no different. In the economic arena, he wanted to build a utopian India. But reality has an uncanny habit of upstaging utopia.

(Yashwant Deshmukh & Sutanu Guru work with CVoter Foundation. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)