A slew of developments taking place over the past four years in Jammu and Kashmir has brought to the fore new realities about the way policing happens in the former state. Immediately after the February 2019 suicide attack on the Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF) motorcade, the Union government stepped up a more organised crackdown against separatists and militant associates.

In hindsight, this was understood as a prelude to the repeal of J&K’s special status. But after the August 2019 episode, many elements of this crackdown have only broadened and, if critics are to be believed, become more arbitrary.

What is becoming increasingly frequent is the trend of barring certain individuals, mostly politicians, journalists, and activists in J&K from leaving the country. Recently, a special National Investigative Agency (NIA) court in Srinagar denied permission to Waheed ur Rehman Para, a political leader from South Kashmir’s Pulwama region, from travelling to the United States to attend Yale Peace Fellowship, in 2023 this year.

Para had a terrorism case registered against him in 2020. The NIA investigators have accused him of harnessing his alleged acquaintance with the militant groups for electoral advantage. But he was issued bail by the Jammu, Kashmir, & Ladakh (JK&L) High Court last year on the grounds that “the evidence as is gathered by the prosecution is too sketchy to be believed prima facie true, that too, with a view to deny bail to the appellant.”

Yet his plans to attend the prestigious fellowship in the United States appears to have come a cropper after the NIA court in Srinagar turned down his request to let him fly to the US. The court reasoned that not only the trial of the case will get hampered, which is at the evidence stage, but there are “genuine apprehensions” of Para fleeing from the country.

The Case of Adverse Background Reports

Paras' is not the only case that has recently sparked a debate around the use of terrorism laws or accusations of anti-national behaviour to preemptively stop people in J&K from flying abroad.

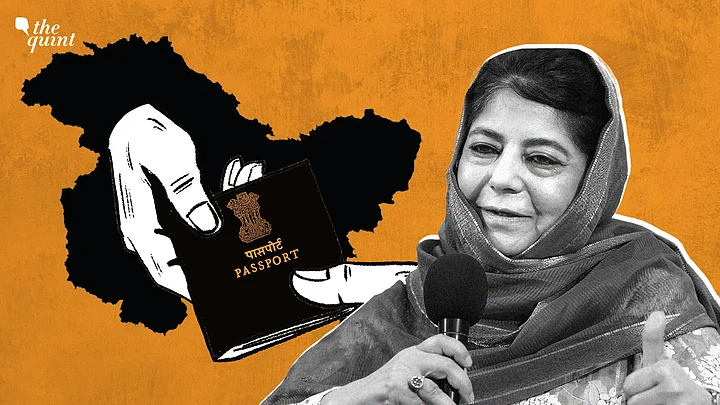

Iltija Mufti, who is the daughter of former J&K Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti was also presented with an “adverse” report from the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) of J&K Police. The unfavourable assessment of her antecedents queered the pitch to obtain a valid passport from the authorities.

Mufti had applied for the renewal of her passport in June last year, but because she was not given a response, she approached the JK&L High Court. Mufti said that she was planning to study for a master's program abroad as she had secured a fellowship offer. Subsequently, the authorities issued her a country-specific passport valid for only two years.

“It wasn’t specified why they issued a country-specific passport to me. My passport expired in January this year. There’s a rule that one cannot travel six months before the date of expiry. So I had to apply for the renewal in June last year,” she told The Quint. “Till February when I hadn’t yet moved to Court, they weren't forthcoming over whether they were renewing my passport or not. Unofficially, it was perhaps understood that I wasn’t supposed to be given. But officially there was no word.”

Legal Framework of Placing Travel Constraints

The imposition of travel restrictions on a number of individuals in J&K has stirred a very hectic debate about the extent to which such moves have legal backing.

“Previously it was limited to separatists and the ordinary youth who may have involvement in protests. But now the dragnet has been extended over to the mainstream politicians as well,” said Dr Sheikh Showkat, a retired law professor in Srinagar.

“In Maneka Gandhi v Union of India, the Supreme Court delivered a historic judgment saying that the right to travel abroad is part of the right to life,” he said, referring to a 1978 unanimous verdict of a 7-judge bench that emphasised the inseparability of Articles 14 (equality before the law), 19 (freedom of speech) and 21 (protection of life and liberty) of the Indian constitution, and broadened the legal understanding of personal liberty.

Showkat said that the decision had wider implications and did help restrict the arbitrary excesses of the executive across the country. The northeastern states and J&K, however, owing to their strife-ridden backgrounds remained the exception, he said.

Scare Over No Fly List Among Journalists

Since the revocation of Article 370, J&K has seen a calibrated clampdown on every expression deemed “anti-national.” And because the term is very vague and over-broad, it has become easier, sometimes, to bring even the critical utterances into its ambit. The immediate fall-out of this has been diminishing journalistic freedom, many reporters working in the Union Territory (UT) say. At least four journalists, including one Pulitzer Prize awardee, have found themselves barred from flying abroad in recent times. Even if there is an FIR against them, they have not been informed about it.

“These exercises are very arbitrary,” one lawyer at JK&L High Court said, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “Even if one is accused of something, it is not easy to restrain their freedom to travel. It is only after the Court is convinced of the apprehension that the person in question may try to escape the law, and when the Court enshrines such conditions in their bail, that they can be legitimately stopped from travelling.”

However, the lawyer added, that the Passport authorities can stop one from flying out of the country or impound the Passport. “But even then they will have to furnish reasonable grounds. Sweeping allegations won’t suffice,” he said.

The fear of finding oneself de-boarded from the plane has been such that many journalists in the Valley say they have stopped reporting on critical matters.

“Like most, I too have started self-censoring. No one wants to be on that list especially if one aspires to go outside India for studies or on some other fellowship,” a 27-year-old Kashmiri journalist told The Quint, wishing not to be identified. “The no-fly-list has scared all of us. No one is sure who is there and who's not. What crime they have done and what they need to do to not be on that list.”

The Incendiary and Seditious Narrative

Last year, the Director General of J&K Police said that “some journalists” were going abroad and then disseminating a “venomous kind of narrative” from there. “Therefore, as a matter of precaution, you have to keep some people on the watchlist,” he said. “And keeping them on this watchlist, if this means that they should not be allowed to travel abroad, I think it’s quite logical. There have been cases like this before. We can’t make this public.”

When pressed on the question that police had not been able to provide reasons for such restrictions, the DGP said, “Let them go to court. We will see what is to be said.”

Positive Judicial Interventions

Not everyone in the UT appears willing to drag this issue to the judiciary. However, those who did, mostly politicians and their kin, have surprisingly been able to yield favourable judgments from the courts, with the judges sometimes voicing harsh denunciations for the authorities.

It happened earlier this year in January after the JK&L High Court judges rapped the authorities for acting as a “mouthpiece of CID” and instructed them to re-examine the issue regarding the passport to Mehbooba Mufti’s octogenarian mother, Gulshan Nazir.

The judgment observed that “there is not an iota of allegation against the petitioner that may point out to any security concerns”, adding that the Police verification report formulated by law enforcement agencies cannot supersede the statutory provisions the Section 6 of the Passport Act, 1967 that deal with denial of travel documents. “Otherwise also in the report relied upon by the Regional Passport Officer and the appellant authority nothing adverse has been recorded against her with regard to any security concerns,” the court said.

Similarly earlier this month, the Delhi High Court ordered authorities to reissue the Passport to Mehbooba Mufti after a protracted legal battle.

Mufti said she had wanted to accompany her mother on the Hajj pilgrimage. Her passport expired on 31 May 2019. Two months later, as the Union government moved to bifurcate the former state and rescind its semi-autonomous status, Mufti was put under detention. In 2020, she applied for the renewal of her passport but an “adverse” report from CID led to her being denied a clearance on 31 March.

99% Clearance of Passport Applications

Her daughter Iltija says she will also fight till she is issued a valid passport and not the “conditional document” she was given in April. She held a very feisty press conference in April in which she accused the CID of “depriving” her of basic rights. “If you are so confident about your report, then why did you have to invoke the Official Secrets Act? Why do you not want the document to come out in the public domain?”

Immediately after her presser, the CID issued a rare media statement repudiating her claims that passport applications of most Kashmiris are being rejected on the basis of “adverse reports.” It said that more than 99 per cent of applications have been cleared by the passport office since 2020. In 2020, 99.95 per cent of received passport verifications were cleared, the statement said, adding that similar figures for 2021 were 99.68 per cent and 99.61 per cent for 2022.

Terming the practice of antecedent verification as “high-value public service,” the CID said it found that 54 individuals who were given passports without verification in 2017-2018, the years when Mehbooba Mufti was the Chief Minister, had gone to Pakistan to receive arms training, 24 of which were eventually killed while crossing back, or in various gun battles.

“Lives of 12 of these young boys could be saved by the CID after their return from Pakistan, by bringing them under preventive custody so that terrorist-separatist syndicates do not succeed in pressuring them to join terror ranks. Eventually, all of the 12 have been handed over to their families,” the CID statement said.

People in Limbo

However, during a conversation with The Quint, Iltija claimed that the CID data did not take into account those cases where applications are gathering dust inside their offices without confirmation whether they will be cleared or not. “It was only after I approached the High Court that they were roused into action,” she said. “That’s how I came to know that my application was being rejected. A lot of people don’t move to court, either because they don’t have the resources or are fearful. They are in a state of limbo.”

Iltija said that her act of litigating her passport issue has a big upside. “It has opened floodgates and now a lot of people who have the wherewithal are emboldened to fight this denial of their right to travel to the court.”

(Shakir Mir is an independent journalist. He has also written for The Wire.in, Article 14, Caravan, Firstpost, The Times of India, and more. He tweets at @shakirmir. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)