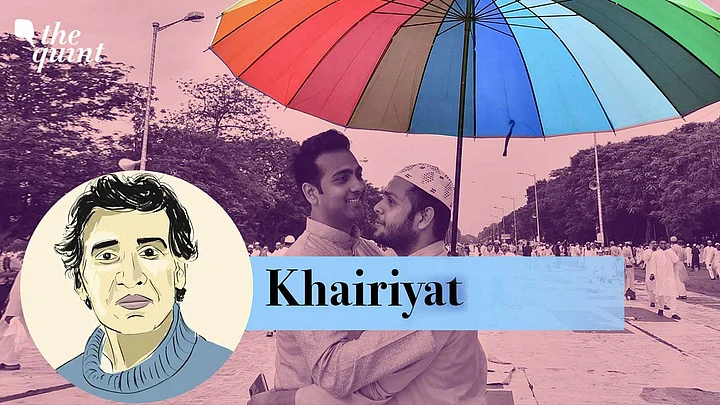

(The Quint brings to you 'Khairiyat', a column by award-winning author Tabish Khair, where he talks about the politics of race, the experiences of diasporas, Europe-India dynamics and the interplay of culture, history and society, among other issues of global significance.)

Anyone who has lived in a good relationship – whether as husband and wife, or parent and child, or sibling and sibling, or friend and friend – knows the value of listening, and of talking in a considerate manner. This is, of course, a mutual matter: both sides, all sides need to do it. Relationships that fail are characterised by a refusal to listen and a tendency to shout, hector, threaten, or fight.

In recent years, the socio-political scene of India has become a tale of failed and failing relationships. This is the saddest thing about what has happened to India in recent decades. It is reflected in the shouting and aggressiveness on display in talk-shows and even ‘interviews’ on Indian TV these days. But it goes deeper than that.

Of course, when ordinary relationships fail, it is usually the moments of happiness and celebration that deteriorate, too. The anniversary dinner ends in an argument; the family gathering disintegrates into disagreement; the old friends’ reunion party becomes an occasion for snide remarks or boasting. Something similar happens when relationships fail within a nation.

When Controversies Become Bigger Than Festivals

Take festivals, for example. Now, it is not as if communal riots did not occur occasionally during, say, Muharram or Holi in the past. But these were rare aberrations, and they were not accompanied by sustained, large-scale hectoring about aspects of the festival. It is this hectoring, usually from very public political and media platforms, that seems to dominate every festival today.

There are needless controversies, about greeting cards or about loudspeakers, etc. Muslim festivals, for obvious political reasons, are particularly accompanied by such controversies. As someone who does not sacrifice animals to any God, I find it repulsive when even such a matter – of the animal sacrifices that religious Muslims offer – is made into an annual controversy, often used to browbeat or demean religious Muslims. Now, the other Eid, the one that marks the end of fasting during Ramzaan and contains no sacrifice, has also become a target of controversies about praying space, loudspeakers etc.

It is true that in the past, too, some Hindus probably did not participate in Muslim or Christian festivals – I recall a friend, now firmly belonging to a particular political party, berating another (Hindu) friend for celebrating Christmas. Similarly, some Muslims did not participate in Hindu or Christian festivals. But there was seldom – actually, never in my recollection – this ‘secular’ political ritual of an annual public hullabaloo over such abstinence.

More commonly, people participated in festivals of other religious communities. My father, for instance, was against boisterous behaviour and alcohol.

He did not visit his Hindu friends on the day of Holi, but went out in the evening to exchange abeer and eat sweets. Hindu friends who were strict vegetarians nevertheless came to our house on Bakr-eid to wish us, and partake in sawai and vegetarian snacks.

Was it because I belonged to charmed middle-class circles? I doubt it. Even the poor shared in each other’s festivals – perhaps more so, as penury often forced them to work together, and live cheek-in-jowl with one another. I think it was, despite the rupture of the occasional riot, the sign of a relationship that worked.

No Relationship Is Perfect, But India Used to At Least Try

It was not the perfect relationship. Almost no relationship is. The occasional riots indicated its lack of perfection. But it was a working relationship, one that had worked for centuries. Its arguments and fights were exceptions, and mostly it managed to conduct a conversation across differences.

We seem to be losing the skill to talk across differences. There is an assumption that we can only discuss civilly if we agree. But, of course, that is a mistake. If you agree, if you are exactly identical, there is no need for a discussion, perhaps even no topic for a conversation.

You can only sit together in a circle, nodding your heads in unison. One needs a discussion across differences; one needs differences for an actual conversation. And, above all, one needs to learn to talk civilly.

Mourning an India Where Conversation Was Possible

India has had a rich tradition of conversations across differences. I was recently reading an account of (Christian) missionary debates with Hindus and Muslims in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. True, sometimes it led to abuse from both sides. A few missionaries insulted Hindu or Muslim beliefs; the occasional missionary was attacked and even killed by Indians. But these were rare. Mostly, it appears, crowds gathered, listening to both sides, and agreeing and disagreeing in a civil manner.

More interestingly, and frustratingly for some missionaries, even when the crowd agreed with the ‘European’ perspective on a religious matter, it did not change its religion.

These largely illiterate Indians had grown up in a civilisation that had long ago learned to live with differences. They were not frightened by the other person’s difference, or alarmed by their own. They could talk civilly across differences.

Today, whenever I return to India and end up watching TV shows with famous hosts shouting, hectoring, or even threatening, I think of those crowds. When I read, again, the annual controversies that erupt around religious festivals today – and are often propagated by politicians and media people – I think of those crowds. And I mourn an India where many more people knew how to create and sustain a healthy relationship.

(Tabish Khair, is PhD, DPhil, Associate Professor, Aarhus University, Denmark. He tweets @KhairTabish. This is an opinion article and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)