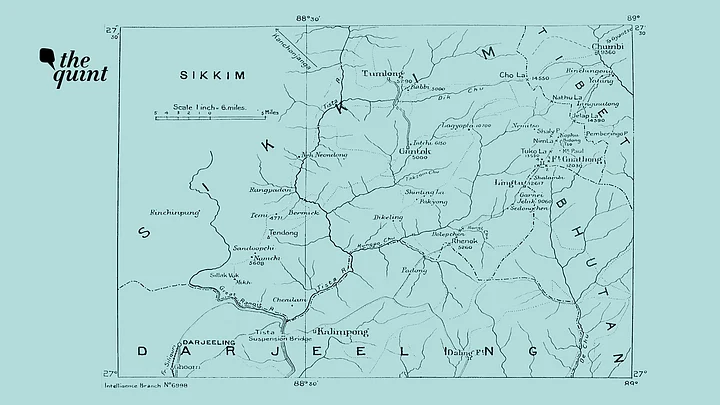

In June of 2017, Indian Army troops confronted China’s PLA soldiers in a plateau area that has been widely referred to as Doklam or Donglang (洞朗) in Chinese. The location of Gipmochi, Gyopmochen or Gyomchen was discussed by strategic experts and journalists, but no clear answers emerged about where this hill was and whether the three names refer to the same geographic feature. Experts, scholars, and journalists relied on historical maps and the treaty of 1890 only, which was signed between British India and China’s Qing Dynasty.

We can now make sense of Gipmochi’s location by examining the Sikkim Palace Archives. In these archives, there is a series of documents exchanged between 1912-1918, associated to a boundary dispute between the erstwhile Kingdom of Sikkim and the Kingdom of Bhutan. The dispute was about an area from Gipmochi hill to Lingthu hill between then Kingdom of Sikkim and the Kingdom of Bhutan. This area of dispute is south of the Gipmochi hill where the military ‘stand-off’ took place in 2017 and doesn’t overlap in anyway with the area of 2017 ‘stand-off’.

Gipmochi’ and Gyopmochen’ Are the Same

The boundary dispute between Bhutan and China is about Doklam plateau, which is north of the location where the military ‘stand-off’ took place in 2017, but now the plateau area close to Gipmochi hill has come to also be referred to as Doklam plateau in the media. I will be using ‘Doklam plateau’ to refer to this area east of Gipomchi hill for the sake of consistency.

We can now say with a high level of certainty that ‘Gip-mo-chi’ and ‘Gyop-mo-chen’ are the same geographic feature located on the boundary between India and Bhutan.

On 4th August 1917, the Britain’s appointed Political Officer of Sikkim (POS) C A Bell wrote “I have the honour to state that a boundary dispute arose between Sikkim and Bhutan in 1912 regarding a tract of grazing land near Gyop-mo-chen (Gip-mo-chi of the maps).”

The same words ‘Gyop-mo-chen (Gip-mo-chi of the maps)’ are repeated again in a letter written by Superintendent of the Sikkim State on 6th August 1917 to POS C A Bell “I have honour to acknowledge the receipt of your letter No. 1539-G dated the 4th November 1917, regarding the demarcation of the frontier between Sikkim and Bhutan near Gye-mo-chen (Gipmochi of the maps), and to say that the Surveyor will be deputed as desired in para 3 of your letter”.

Historical Documents Prove the Border Dispute Didn’t Involve China

On 29th March 1913, the Maharaja of Sikkim Thodup Namgyal wrote to POS C A Bell “The disputed line begins from Gipmochi and runs down Lasa-La spur till it meets the junction of the De-chu and the Gnay-chu river to Rechi-La. He (Rhenok Kazi) found four old boundary pillars along the spur laid down several years back. He also tells me that in another map the boundary line between Sikkim and Bhutan was shown along the Rechi-La ridge to Lingthu, Gnatong and thence a straight line across the hillside of Gipmochi. But there are no old boundary pillars along this except some new ones recently laid down by Raja Uygen Dorji (High ranking Bhutanese official)”.

On 10th August 1912, the Maharajakumar Sidekong Tulku Namgyal, the son of the then Maharaja of Sikkim Thutob Namgyal wrote to the Political Officer

“From Lachminarain Rai Sahib I learn that the land really belongs to this State (Sikkim) as there are old pucca as well and kutcha boundary pillars further away on the true boundary line. Raja Ugyen Dorji’s actions in encroaching upon Sikkim and erecting boundary pillars of his own accord wherever is liked is simply jubberdasti (coercion)”

Rai Sahib Lachminarain was a Newar official of the state of Sikkim during the rule of Sikkim’s Maharaja Thodup Namgyal.

How the British Lamented the Loss of Gipmochi to Bhutan

The Treaty of 1890 refers to the boundary between British India and Imperial China; in relation to Mount Gipmochi:

“The boundary between Sikkim and Tibet shall be the crest of the mountain range separating the waters flowing into the Sikkim Teesta and its affluents from the waters flowing into the Tibetan Mochu and northwards into other Rivers of Tibet. The line commences at Mount Gipmochi on the Bhutan frontier and follows the above-mentioned water-parting to the point where meets Nipal territory”

The Palace Archives offer further insight about the area adjacent to Gipmochi hill.

In the 1917 letter—cited earlier—C A Bell alludes to geography towards the north and the south of the Gipmochi hill “The actual fact is that the piece of land, which should, but for a mistake, have been included in British territory, in now, in all its lower portion, in the de facto possession of Bhutan, while the upper portion has come to be regarded by usage as belonging to Sikkim. In practice the mistake has caused no inconvenience, so it is not proposed to disturb existing arrangements”

The lower portion here refers to the area falling east of Lingthu hill and the upper portion falls under an area east of the of the Gipmochi Hill – covering parts of Doklam plateau.

China Not a Party to Historical Boundary Dispute

These archival documents show that the discussion about the control of area around Gipmochi hill was between Kingdom of Sikkim and the Kingdom of Bhutan. People’s Republic of China has often alleged that the British Colonial Empire used the chaos resulting from the fall of the Qing dynasty to transfer the control of certain boundary areas. But these letters and other communications in the Sikkim Palace Archive demonstrates that the areas adjacent to Gipmochi hill – both east and west – were a matter of discussion only between the kingdoms of Sikkim and Bhutan.

It should be noted that neither the Kingdom of Bhutan nor the Kingdom of Sikkim were a party to the Treaty of 1890, signed in the then city of Calcutta.

A close analysis of the Sikkim Palace Archives reveals that the Article I of the 1890 treaty may not precisely map on to the current delineation of the border between China and India in Sikkim. The international principles of drawing the boundary by the watershed zones and the archives other than the Treaty of 1890 will need to be considered when discussing matters of boundary delineation in this particular context.

(Aadil Brar is a freelance journalist. His work has appeared in the BBC, The Diplomat, The Wire India, Devex and other publications. He was also a National Geographic Young Explorer grantee between 2016-17, during which he lived and worked in Sikkim, India. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)