Nanak Singh (1897 – 1971) needs no introduction among readers and admirers of Punjabi. He established himself over the Punjabi literary landscape in the 20th century with a staggering output of more than 50 novels, short fiction, poetic collections, plays, essays, and even translations.

It is remarkable that in addition to the many accolades he received throughout his life, he did not get a Nobel Prize in Literature, a distinction he shares with his fellow Punjabi behemoth Amrita Pritam!

Recognition has also eluded the father of the Punjabi novel in his native birthplace, Chak Hamid, now lying in Jhelum in the Soan valley in present-day Pakistan. Perhaps with this in mind, Singh’s grandson Navdeep Suri, a distinguished diplomat in his own right, began a rather belated but much-needed effort to translate his grandfather’s work into English.

What makes Nanak Singh’s work important, interesting, and worthy of attention on this side of the border is not only the fact that he is a son of the soil who was also a witness to some of the horrific events of 20th-century Indian subcontinent such as the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre and the partition of India (he died in the dying days of the creation of Bangladesh) but also that he was an ardent advocate of Punjabiyat, irrespective of the compulsions of faith, caste, class, and politics that were to drive a permanent wedge in the land of the five rivers in 1947.

The Division of Nanak Singh's Beloved Punjab

The novel under review, Khoon De Sohile (translated as ‘Hymns In Blood’), takes its title from a verse of the Guru Granth Sahib written at the time of Mughal king Babur’s maiden attacks on India in the 16th century. However, the full import of the title only registers towards the conclusion of the novel.

What Pakistani readers will find interesting is that the novel is set in the Chakri village of the picturesque Soan valley of the Pothohar, an area which also provides material for that other distinguished literary son of Pothohar, the renowned Urdu writer Ahmad Nadeem Qasmi. However even before one gets to the novel itself, it is the highly polemical foreword to the novel by the author which grabs the attention of the potential reader.

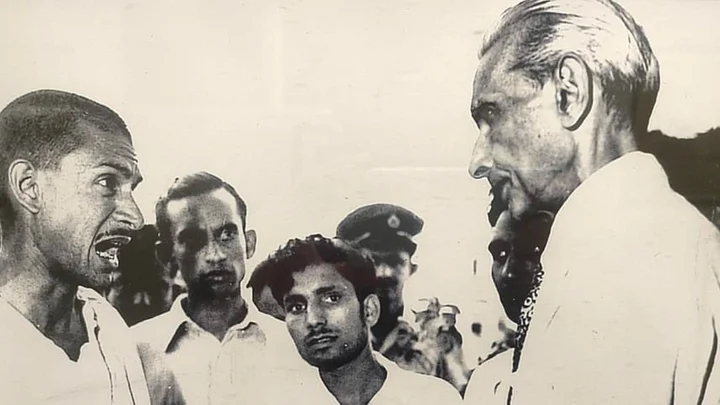

For Nanak Singh, his objectivity perhaps overtaken by the tragic events of the Partition, writing in the white heat of the moment, excoriates Jinnah and his Muslim League for being little more than British pawns and being the reason for the partition of India. A little before denouncing Jinnah and his party, he asks whether the blame for the partition should be put on the British or the myopia of the natives.

One wishes that a writer of Nanak Singh’s caliber would also have paused to consider firstly, that not all Muslims were supportive of partition, in fact, some towering nationalist Muslim leaders with real roots in India like Maulana Hussain Ahmad Madni, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, Maulana Maududi, Maulana Hasrat Mohani and Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi expressly opposed it.

Secondly, would Nanak Singh also use the same words for the Congress leaders like Gandhi and Sardar Patel who had injected communalisation in the political atmosphere of the 1940s by using Hindu religious imagery and vocabulary like the Rama Rajya, thus heightening the insecurity of some Muslim leaders like Jinnah and propelling the demand for Pakistan forward?

Perhaps what is really speaking through the anguish of Nanak Singh’s words here is not the actual partition of the country itself but the division of his beloved Punjab.

Be that as it may, the novel begins amid the backdrop of a budding teenage romance between Naseem, the major female protagonist of the novel, and Yusuf, a somewhat wayward lad who often manages to get his way with the former, peppered by fits of violent anger.

Story of a Doomed Romance

It may be tempting to read the novel merely as the story of a doomed village romance where Naseem, though hopelessly in love with Yusuf, also knows that because of Yusuf’s wanton ways the two cannot really be together; and not just a partition novel.

More than half of the novel is dedicated to exploring the doomed love story where apart from Naseem, the only other well-fleshed-out character is the Sikh sage Baba Bhana, the oldest man in the village who had made a pledge to the girl’s dying father to be like a father to her in times good and bad.

The device of a Sikh writer basing the romance on two Muslim characters is an interesting one since it allows Nanak Singh to make recurring parallels with the classic Punjabi doomed romance of Heer Ranjha as well as Yusuf and Zulekha.

Also, the fact that the two main protagonists of the novel are Muslim and Sikh, and then later in the novel, it is the two minor Muslim characters of the village, namely the munshi and the maulvi who instigate sectarian tensions, allows Nanak Singh to justify his thesis that it was the Muslims led by the Muslim League who broke away from India. But credit to the novelist that he truthfully and accurately brings out his Muslim characters.

There is, however, not just the disappointments of the doomed romance between Naseem and Yusuf or the political vicissitudes that sustain the reader’s interest and keep him guessing as to the fate of both.

With the conclusion of winter and the arrival of Lohri, there is a pleasant interlude with what is to follow.

There are fine passages describing a common ethos in celebrating Lohri, a secular festival like Halloween in the Western tradition or Basant, heralding the arrival of spring. For anybody here in Pakistan who wants to know what these festivals were like, extinct as they are in the Pakistan today, this novel provides ample scenes of rivalry and revelry between groups of boys and girls.

For this reader, nowhere has he read the joyful extempore tappas and mahiyas composed in riposte, as in this novel, paralleled only by Qasmi’s descriptions in the original Pothohari. Here is a sample:

Like the flower of a pomegranate,

I am most handsome among the boys.

Now, who’s the loveliest among the maidens?

And in response,

Stand in the corner, miserable pervert

I’m like your sister, don’t forget

Go find a harlot if you want to flirt!

Horrifying Passages Highlighting the Carnage

As the communal wave arrives in this quiet corner of Punjab, such norms are relegated in the onrush towards the inevitable – the expulsion of the village’s tiny non-Muslim population by hordes of Muslim vigilantes and retribution for the members of the majority who strive to protect the former.

Baba Bhana, with his failing eyes, and Naseem with her flailing heart are forced to flee Chakri amid scenes of loot, plunder, and wanton bloodshed that will be familiar to readers of Saadat Hasan Manto, Krishan Chander, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Abdullah Hussein, Bhisham Sahni, Qasmi and Pritam.

However, Nanak Singh also documents the exceptions among the Muslims who put themselves in danger to go out of the way to ensure the safe passage of Baba Bhana and Naseem:

Muslim families, firmly believing in the same God as the marauders, had taken it upon themselves to provide succour to their non-Muslim friends, often guarding them with the ardour with which a hen protects her flock of chicks.

Incidents like these weren’t confined to a village or two. Every village in the area had its own story of Muslims who provided shelter to Hindu and Sikh families and either saved them from certain death or tried valiantly to shield them... The Muslim population of Chakri was widely regarded as the most tolerant and trustworthy in this part of Pothohar.

Unsurprisingly Nanak Singh was one such soul who helped save many Muslims in Amritsar from Hindu and Sikh hordes when they were fleeing to Pakistan.

I felt haunted by this particular passage describing a scene of carnage that undoubtedly must have repeated itself ad nauseum across the subcontinental divide that tragic summer of 1947:

The sound of running feet. Huddled bodies are illuminated by a passing mashaal. The flash of metal. Cries of terror. A sudden deathly silence. Young women are being hauled away on brawny shoulders, legs flailing helplessly. Screams fall on deaf ears. Trunks, baggage, bundles, and other loot piled up for distribution. Corpses of men and women kicked around and searched. Earrings and necklaces were ripped off the lifeless bodies. Pockets turned inside out and emptied. Clothes torn off to find cash and jewellery tucked away in the folds. A whoop of joy as a man’s waistcoat or a woman’s salwar yielded an unexpected treasure. Bundles of currency. Gold coins twinkle in the moonlight.

The swords and spears were used with such violence that the victim was usually dead in the first blow. A scream, a moan and then silence. The group following the first lot kept its eye on the bodies. A twitch or whimper and they would return to stab the victim and make sure that he was dead. It was like they had sworn that there would be no survivors from the pathways leading into the cave.

Hymns In Blood is a welcome addition to partition literature in translation in the 76th year of the division of India. It will certainly bolster Nanak Singh’s reputation in his native land, where none of his works are regrettably read or reviewed to date, even in translation.

(The author is a Lahore-based, award-winning translator and researcher. He was the first Pakistani reviewer of Nanak Singh’s ‘Khooni Vaisakhi’. This is an opinion piece, and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)