On 9 November 2019, I was in an Uber on my way to an arbitration venue. As Chief Justice Gogoi began reading out an anonymously-authored, unanimous judgment on behalf of the Court, I kept on continuously narrating it to the cab driver, much like my namesake had done to a blind king many yugas ago.

With every update such as the vandalism was wrong, the claimants had not been able to establish their legal title, secularism is the basic foundation of the nation, my cabbie got worked up and apprehensive.

By the time the Court got to pages 116 to 125 of its decision, where it devoted about nine pages to the Places of Worship (Special Provisons) Act, 1991 to admiringly note how this law had put the lid on the genie of future battles over places of worship, leaving only the Babri Masjid issue to be judicially resolved, he couldn’t contain himself any further.

He called his wife and said that the Court had ruled in favour of the “Muslims” and that there could be law and order issues in the city and that she should take precaution.

What the Fateful Day of the Ayodhya Judgement Rung In

Then came the climax. The operation was successful but the patient had been granted an alternate plot of land. The Court felt that as many, including the vandals, believed that Lord Ram was born on the disputed land and the same should be judicially delivered to that side.

The anonymity of the Ayodhya judgement was not the only unprecedented event of the day. As the day unfolded, the five judges posed for a group photograph which was released to the media. When that eventful day ended, we learn from Mr Gogoi’s book, the Chief Justice graciously took his brother judges for a celebratory dinner and good wine at a five-star hotel. This was followed by another group photograph— this time all five holding hands in solidarity! Gogoi ensured that this photo was included in his book.

As the judges retired for the day after a sumptuous meal, the nation also breathed easy as no untoward incident or flare-up had been reported in reaction to this momentous verdict.

The 1991 Law Remains Contentious

The anonymous verdict, unlike an equally anonymous “addendum” containing the musings of one of the judges, was a masterpiece in judicial writing. It managed to create judicial history while appearing to be fair and even-handed.

A reader would be so taken by its beauty and impartiality and steadfast adherence to the constitutional vision, that he/she could be excused if failing at the first attempt to grasp how it ultimately wound up not in ‘law’ but in ‘faith’ and directed the vandalised to move out of the site. So, the poor cabbie and yours truly could not be faulted for our respective initial reactions.

The positive takeaway was that the Top Court had given its seal of approval to the the Places of Worship (Special Provisons) Act, 1991, a position now disputed by the Solicitor General in the subsequent proceedings where this law stands questioned. The 1991 Law was unique as in it, was a response to the times when the slogan was “yeh to sirf jhanki hai Kashi- Mathura baanki hai” (“this [i.e. Ayodhya], is just an introduction, Kashi and Mathura are still left to be addressed.”)

The 1991 Law prohibits any legal proceedings in any court to alter the status quo with respect to the religious character of any place of worship as it stood on India’s day of independence. It, however, carved out an exception for the Babri Masjid dispute.

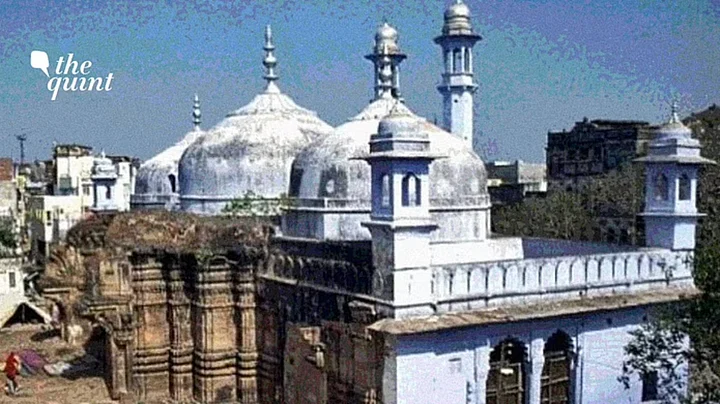

History Repeats Itself With the Gyanvapi Mosque Row

It is precisely to get over this prohibition that a civil suit was contrived in the name of a few ladies wanting to perform Gauri puja in the Gyanvapi Mosque built on the site where the Shiva temple stood in Varanasi.

The defendants relied on the 1991 Law to nip the suit in the bud. However, the civil judge directed an inspection which led to the discovery of the now famous “shivling”. The muslim side appealed against the inspection process and undaunted by defeat in the Allahabad High Court, the matter made its way to the Court of Justice DY Chandrachud—the now Chief Justice of India designate.

Given the fact that the secret author of the Ayodhya verdict is the Bar’s worst-kept secret, many were hopeful that this Court would spare no effort to keep the lid on the Pandora’s Box. All it had to do was rely on its own judgement in Ayodhya which it had so heavily relied upon the 1991 Act.

Varanasi Court Quashes Carbon Dating Plea

It could also draw strength from the fact that, though eight years had passed, the present government had made no effort to modify the law. In fact, even till date, the Government of India has not been able to take a stand on this law before the Supreme Court.

In an order which will, in the course of time, prove to facilitate the gravest assault on secularism and communal amity, the Court refused to quash the proceedings. It opted for a compromise and transferred the suit to a senior judge.

While the civil judge has dismissed the application to reject the suit filed by the defendants, ensuring a long legal battle ahead, it has also recently dismissed an application by the plaintiff for carbon dating the alleged ‘shivling’.

This is a positive development as no purpose would be served by it. It is nobody’s case that Aurangzeb had not vandalised the Kashi temple. The issue is whether we, as a society, are willing to move on from that historical wrong.

The 1991 Law has ensured peace for over two decades-- a period during which India has witnessed tremendous growth and development. Some may say that the 1991 Law has sidestepped the real controversy and left the wounds of history unaddressed. Both views have merit and emotions run strong on both sides of the divide. There is an ancient Chinese curse “May you live in interesting times”— the present could not be more interesting!

(The author is a senior advocate practising in the High Court of Delhi and in the Supreme Court of India. He tweets @advsanjoy. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed are the author's own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)