UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak dropped a bombshell with a comprehensive cabinet reshuffle on 13 November, triggered by the antics of (former) Home Secretary Suella Braverman, who was sacked by 10 Downing Street.

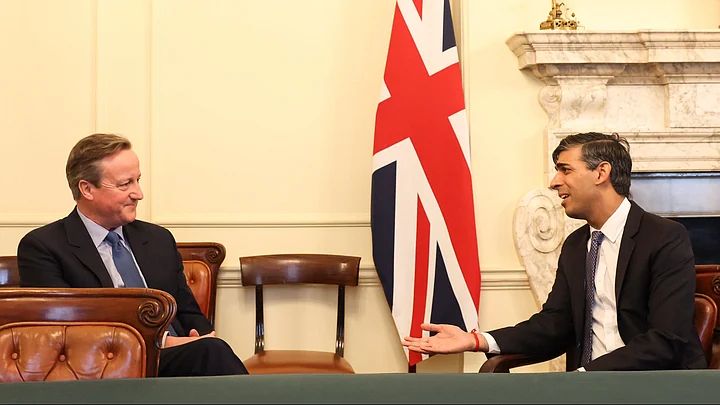

The return to frontline politics of David Cameron as foreign secretary, however, dominated the headlines in the British papers. Both Braverman’s departure and Cameron’s return could signal the trajectory of the country's politics heading into the election season.

For some, Braverman’s departure is a strategic retreat to improve her right-wing profile and succeed Sunak as the leader of the Tories in case Labour wins the 2024 general election. For others, she is the only Home Secretary in British history who was fired from this position not once, but twice.

For his part, Sunak made sure that the media hype around Braverman’s departure was eclipsed by other news.

The cabinet reshuffle and return of David Cameron is being hailed as a strategic masterstroke by Number 10, at least by the PM's supporters, who try to depict it as a bold recalibration of the political agenda. Most others, however, see it as a sign of desperation and Sunak’s last chance to regain some political momentum ahead of the election.

Brief Recap of Cameron's Career

Perhaps a quick recap of Cameron’s career is needed, as seven years have passed since he resigned as prime minister, and the UK has had six foreign secretaries since then.

Cameron’s political odyssey spans decades, not without its fair share of controversies. Serving as PM from 2010 to 2016, he navigated the Conservative Party through the labyrinth of coalition governance alongside the Liberal Democrats.

Cameron’s claim to fame, or perhaps infamy, rests on his austerity policy, a course of severe budget cuts and fiscal tightening after the 2008 financial crisis. Widely criticised for its impact on public services and the social safety net, this policy ignited fierce debates lasting until 2016.

The 2016 Brexit vote emerged as the most contentious chapter in Cameron’s legacy.

Despite advocating for the UK to remain in the EU (European Union), a narrow majority opted for departure, compelling Cameron to tender his resignation from the top post.

His decision to greenlight the referendum is still viewed by many in Britain (and Brussels) as a political miscalculation with far-reaching implications for both domestic and foreign policies.

Cameron’s Foreign Policy Profile

How would Cameron's return affect the UK’s place in the world?

Cameron’s leadership of the FCDO (Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office) is unlikely to result in significant changes in the UK’s relationship with the US and India.

Dr Jaishankar was the first foreign guest to congratulate Cameron in person on his appointment, but this was owed to chance. Regarding China, Cameron demonstrated a “pragmatic” approach when he was the PM, seeking to balance the promotion of robust trade relationships with concerns about human rights violations.

Conservative Sino-sceptics will be keeping a watchful eye on how the UK’s China policy develops under Cameron as foreign secretary, also because Cameron served as an adviser to Western companies and investors with businesses in China, while the Sino-American rivalry steadily deteriorated after he left office.

Other foreign policy files could prove to be even more complicated for Cameron, namely Europe and the Middle East. Much will depend on concrete developments on the ground.

Cameron’s authorship of the Brexit saga will not earn him much credit when negotiating with the EU.

Still, some of his other policy decisions could benefit the UK’s standing in Europe. His vocal support for Ukraine during the first Russian invasion in 2014 earned him acclaim, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe. It is very likely that he will seek to build on this, and it is almost certain that the UK’s strong support for Ukraine will continue seamlessly.

Regarding the other big geopolitical challenge of the day, Cameron championed the two-state solution for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict throughout his tenure as PM.

However, his policy vis-a-vis Israel drew mixed reviews, with some commending it as a balanced approach and others decrying perceived leniency. This could become a point of contention, although polls indicate the Israel-Palestine conflict does not significantly influence most voters’ decisions in the UK.

Cameron's Role in the Tories' Election Campaign

Rather than making grand foreign policy decisions to impress the electorate, Cameron could fulfil another purpose in Rishi Sunak’s election campaign. Both Labour contender Sir Keir Starmer and the Sunak have acknowledged that the next election will be won by the party that most credibly demonstrates its commitment to change.

While counterintuitive at first, Cameron could help Sunak to represent this 'change' by appealing to voters’ nostalgia, coupled with, perhaps naively, fond memories of calmer times in British and world politics.

Appealing to voters’ emotions and downplaying the economic and political fallout from Brexit, COVID-19, and Russia’s war on Ukraine, as well as memories of more chaotic Conservative leaders like Boris Johnson and Liz Truss, seems like a high bet.

High but not impossible. Yet there are high risks as well.

Cameron’s appointment as foreign secretary is being criticised as undemocratic, as he is not an elected Member of Parliament and cannot be questioned by the parliament unless he is summoned. Indeed, to be eligible to serve in the cabinet, he was given a seat in the House of Lords, making him the first former prime minister to be ennobled in this manner since Margaret Thatcher in 1992.

The fact that the foreign secretary is not subject to the same scrutiny as other ministers, during an extremely difficult period of geopolitical tensions no less, will give critics some ammunition. Cameron’s ennoblement will also reinforce the criticism he faced over his political lobbying on behalf of foreign banks and investors, including with the chancellor then and prime minister now, Rishi Sunak.

For Sunak himself, while the reshuffle may garner him more support from close allies, it also intensifies opposition on the backbenches. A clear stance from Number 10 on the reshuffle will be crucial as pressure mounts to explain the personnel decisions. It remains to be seen whether these changes signal a new approach to contentious issues like Brexit and migration.

Critics on the backbenches have so far expressed dissatisfaction with Cameron’s appointment as foreign secretary instead of a member of the parliamentary faction.

Whether this dissatisfaction will spill over to the party’s rank and file, and eventually (possibly after the election) strengthen voices to bring back Braverman is still an open question.

(Magnus Obermann is an Associate analysing geopolitics at Global Counsel. This is an opinion article and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)