(This is the second part in a two-part series on the Assam-Mizoram border dispute and conflicts in the Northeast)

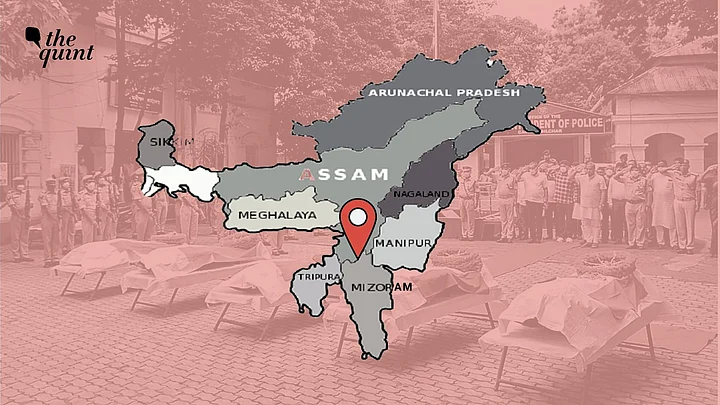

The conflict at the Assam-Mizoram border shows us an interesting development within the Indian state — minorities have long been victims of conflicts in the Northeast. And the Centre hasn’t played a positive role to resolve the fault lines. Far from it, it has treated the region as separate from the rest of India and used force to quell demands for freedom. In parallel, the region has become fraught with additional issues, of imagined political and cultural spaces, which are deep-rooted.

The Use of 'Legitimate' Violence

Sociologist Max Weber defined the state as the only institution that can claim a monopoly over the use of legitimate violence or use of force, particularly on its own people within its territory. For instance, Mizoram became the first state where the Indian government used its Air Force to bomb the civilians in 1961. This was a one-sided use of the legitimate authority of the state to show its power and sovereignty.

The border dispute highlights something more profoundly disturbing and worrying.

We should ask what emerges when two state forces use legitimate violence on each other. Such claims to legitimacy to use force are what explains the exchanges of blame from both sides, on Twitter and on the ground. The citizen is trapped in such a contestation over legitimacy.

In this fight over legitimacy, when the Mizoram Chief Minister insinuated that the aggressors from the Assam side were “Bangladeshis”, the Assam Chief Minister inadvertently admitted that Bengali/Sylheti Muslims are indeed Assamese. Borders can indeed make one speak a different tongue.

This admission is significant as Cachar has been deemed to be a “cancer” of Assam among Assamese hardline nationalists. Dividing Assam into Brahmaputra and Barak also figures every now and then, when the question of language, citizenship, or territory is brought into question.

Northeast Is Not Just A Resource Zone

In essence, the fault lines of such border disputes are also to do with how the Indian state has treated the Northeast region as a frontier (tea, oil, coal, dams), as if the people living there are lesser beings. It has treated the Northeast as a resource zone, and later, with Look East, it envisioned turning it into a corridor to South East Asia. The Northeast has always been seen as a region that is “different” (racially, culturally, and politically) from the rest of India. It is also a highly militarised zone that has been treated with exceptional laws, such as the Armed Forces Special Powers Act.

Morarji Desai stressed giving importance to the territory over people in the Northeast, and that is a case in point. Commenting on the Look East policy, Pranab Mukherjee once said, “Geography is opportunity." The language of “exterminating all rebels” used by the then Congress government suggests how territory must be guarded at all costs (particularly during Naga talks in the late 1970s), even if that means “exterminating” its own people who were asking for “freedom”.

The demand for freedom from India rests on claims that many of its territories were forcefully included in the Indian union against the wish of the people. Different insurgent groups that took birth in the Northeast were a response to such existing dissensus.

Imagined Cultural And Political Spaces

Parallelly, the border also exemplifies ambiguity, mobility, vitality, creativity, and restlessness. They are like allegories that can zip up social realities and surprise us at all points of history, such as in this Assam-Mizoram conflict. As anthropologist Anna Tsing would call them, they can be viewed as ‘awkward engagement or cultural friction’. One such friction of the border is the imagination of cultural or political space we see among various nationalities in the Northeast.

The Assamese literati in the early decades of the 20th century were conscious about the demands of “greater Assam”. Expanding the influence of Assam or its language, Assamese, was taken up actively in places like the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA, present-day Arunachal) by the Assam Sahitya Sabha. The Mizos also demand a larger space to be brought under their imagination of a cultural place for all the people who relate to the Zo identity; some of those spaces fall in today’s Burma.

On the other hand, we also are aware of the demand of the Nagas for Nagalim (Greater Nagaland) comprising territories in contemporary Nagaland, parts of Manipur, Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, and Burma. All these unresolved questions of expanding one’s cultural or political geography suggest that the border issues are much more deep-rooted in the imagination of the people of the region.

Of course, we shouldn’t lose sight of the colonial background of the existing border issues among the Northeastern states, that colonial cartography and administrative divisions made for the colonial administration did harm the understanding of social, cultural, and political boundaries between contiguous and political communities. We all bear its brunt, but it is carried much more by people who live around political borders in India today.

The name-calling, stigma, and essentialism seen from both sides in Assam and Mizoram show us how a space can be contested and imagined in myriad ways. Neither is the Northeast a monolithic space nor is the indigene or indigenous politics sanitised from racist and populist tendencies. This conflict is a lesson to let go of our imagined, romanticised perceptions of ourselves and others. It also tells us to think of the national and regional as connected entities and calls for treating both equally. This is essential to make sense of the state and its people with their multiplicities.

(Suraj Gogoi is a Ph.D. candidate in Sociology at the National University of Singapore. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)