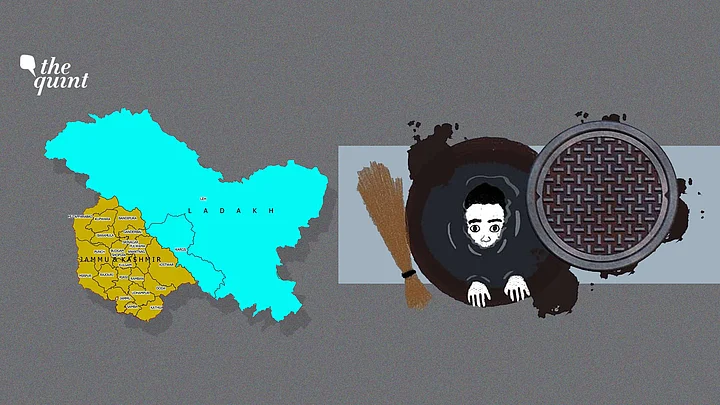

The invisibilization of the subaltern group of Watals looks set to increase in a new Kashmir grappling with anxieties over loss of control over land and occupation by non-Kashmiris.

The abrogation of Article 370 has generated several narratives, most of them focused on how the move would exacerbate or end the three-decade old conflict in the Kashmir Valley. Unsurprisingly, the Watals – a historically marginalised social group of Kashmir – have found little space in this discourse.

In the early summer of 2019, I visited Srinagar’s densely populated Sheikh mohallas or colonies, that is, ghettoes where Watals or ‘hereditary’ manual scavengers and sweepers live. Here, I encountered shared stories of generational poverty, deprivation, and discrimination.

‘No Takers For A Poor Man’s Daughter – A Sheikh’s Daughter – In Kashmir’

At Bachi Darwaza – one of the Sheikh ghettoes that dot the peripheries of Srinagar’s Old City – I met two daily wage workers, Bilal Ahmed Sheikh and Abdul Majid Ghanai, who narrated their daily struggles, particularly how curfews imposed by the Army and shutdowns called by separatists deprived them of opportunities to seek work.

At Zahid Pora, I came across Mohd Ismail, a retired sanitation worker of SMC (Srinagar Municipal Corporation), owner of a dank one-room shack with a brick and tarpaulin toilet built next to it. Gaunt and emaciated, Mohd Ismail told me:

“My meagre pension of Rs 4000 is barely enough to make ends meet. I have no money to arrange a wedding for my daughter. A loan I took for my operation is yet to be fully repaid. Even she has had a surgery which has left an unsightly scar across her belly. There are no takers for a poor man’s daughter, a Sheikh’s daughter, in Kashmir.”Mohd Ismail, a retired sanitation worker of SMC

With stinking open drains, snarled overhead wires, potholed streets, and warrens of ramshackle homes, these mohallas – mostly encroachments – reveal a starkly different side of squalour-free Srinagar. A poor city tucked beneath a rich city.

Caste In Kashmir: Why Most ‘Sheikhs’ Are Landless & Live In Poverty

Like the Dalits of mainland India, Watals are an endogamous social group in Kashmir associated with ‘polluting’ jobs such as skinning animals, scavenging, and sweeping. Categorised as OSC (Other Social Castes) in government records, Watals evidence the Valley’s entrenched caste system. Sheikhs – community of sweepers – are a sub-group of the Watals and not all Watals are Sheikhs.

Most Sheikhs are landless and live in abject poverty.

In his book Directory of Caste in Kashmir, Kashmiri sociologist Bashir Ahmed Dabla classified Kashmiri castes into three different groups. At the top are the ‘Syed castes’ – Geelani, Andrabi, Qadri, and Bukhari. Below them are ‘occupational castes’ which include surnames like Wani, Bhat, Lone, and Khandey. At the bottom of the caste hierarchy are ‘service castes’ such as the Hanjis (those who dwell on water bodies), Bangi, or Sheikh.

The ‘Partial Brahminization’ Of Kashmir

Dr Fayyaz Ahmed, Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Kashmir, explains the root of caste in the Valley:

“Brahmins – when the Kashmir Valley was predominantly Hindu – formed the educated elite who enjoyed enormous power and respect. Understandably, their hegemonic social codes remained in place long after people converted en masse to Islam. Accordingly, jobs considered ‘polluting’ in Brahmanical society such as manual scavenging and skinning animals continued to be looked down upon. Likewise, Kashmiri Pandits or Brahmins traditionally ate the flesh of lamb and goats and like Hindus everywhere, abstained from beef. Although Islam’s dietary laws permit beef consumption, it is still considered a poor man’s meat in the Valley. My colleague Dr Farah and I have termed this process of cultural and social emulation ‘Partial Brahmanization’.”Dr Fayyaz Ahmed, Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Kashmir

Interestingly, traditional Wazwan – Kashmir’s famed multi-course feast – predominantly consists of mutton dishes.

Like in the rest of India, the politics of surname plays out in intriguing ways in the Valley. Adnan Bhat wrote in The Wire: “Sheikh is an interesting caste here. If this title is used as a prefix, it indicates the person has descended from Brahmin landlords like the National Conference party leader Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah. If, however, Sheikh is used as a surname, this indicates belonging to the sweeper community.”

Among the ordinary Kashmiris I spoke to, the common (mis)perception is that Watals today are well-off owing to reservation in state government jobs.

A few persons even told me that Watals engage in thievery and prostitution. ‘Watal’ and ‘Sheikh’ are in fact abusive slurs in the Valley. This attitude alludes to a collective mindset that is steeped in deep-rooted prejudice.

Despite the absence of overt caste violence, the dominant castes’ refusal to socialise and form matrimonial alliances with these groups indicates that caste is one of the most divisive forces in Kashmiri society.

Do Sheikhs Have No ‘Azaadi Aspirations’?

For most underprivileged residents of Sheikh mohallas, the anxiety to earn a livelihood outweighed the desire for self-determination. Lockdowns and curfews were widely held as the greatest hurdles to economic betterment and a better future for children. Among the persons I interviewed prior to the scrapping of Article 370, I neither encountered an aspiration for Azaadi, nor unequivocal support for India. Most saw themselves as victims of an unfortunate situation.

However, notwithstanding frustration and disappointment, there isn’t a total disconnect with the movement. “Kashmir is a conflict zone and involvement in the Azaadi movement is not a facile phenomenon” explains Masood Hussain, senior journalist and founder-editor of Kashmir Life magazine.

“There are degrees of involvement. For instance, observing a shutdown when a call is given by the separatists and respect for martyred militants may be interpreted as implicit support for the movement.”Masood Hussain, senior journalist and founder-editor of Kashmir Life

In the same vein, Dr Fayyaz says, “The community is not a homogenous one. There are participants and non-participants. Besides, peer pressure ensures there is a measure of respect for the separatist movement. Indeed, the Sheikh community has produced several well-known militants, Jalaluddin Sheikh and Ramzan Sheikh to name a few.”

Post-370, A Deep Distrust Of Indian Govt

However, there seems to have been a shift since the abrogation of Article 370 and bifurcation of the state into two Union Territories (UT) followed by an unprecedented lockdown (which was followed by another interminable COVID-19-induced lockdown). The former ambivalence mixed with a desire for peace has metamorphosed into a deep distrust of the Indian government and a feeling of foreboding with regard to Kashmir’s future.

25-year-old Ayyaz Ahmed Sheikh, son of a permanent safaikaramchari, tells me:

“I work as a fruit vendor; I am not sure I’ll ever get a government job. The common perception here is that the PM does not like Muslims or Kashmiris, and his administration is punishing us. People are living in fear of their land and livelihoods being snatched. The sense of impending doom has been exacerbated by the pandemic. With no employment opportunities and a whimsical government, the future appears dark.”25-year-old Ayyaz Ahmed Sheikh, son of a permanent safaikaramchari

Shams Irfan, Kashmir-based independent journalist, echoes a similar sentiment, “Kashmir is being ruled by the Centre. There is hardly any understanding of local issues. Besides, being an authoritarian government with no accountability, there is no desire to reach out to these marginalised sections or analyse their problems. Their situation is only set to worsen under this regime.”

Threat To Sheikhs After J&K New Rules: Why Future Sheikhs May Become ‘Homeless’

Significantly, reservation extended to Watals under OSC (Other Social Castes) category has been increased under the UT administration’s new rules.

“Under S.O 127 notified on 20 April 2020, reservation for OSCs in government jobs has been increased from 2 percent to 4 percent. For Economically Weaker Sections (EWS), it is now 10 percent; it was zero percent earlier. Persons from the Sheikh community may also avail of this category. These groups are not aware of the rules. The government is doing all it can to uplift the underprivileged sections of J&K.”Khurshid Ahmed Sanai (KAS), Additional Secretary of the Social Welfare Department

Ironically, the EWS category may do more harm than help. Dr Fayyaz says:

“With domicile certificates being given to anyone who has resided in the UT for 15 years, the EWS category will throw open the doors to outsiders availing government jobs under this ten percent quota. Since the Sheikh community may also avail themselves of this quota, they will face more competition, and tougher times ahead. Moreover, there is a general perception that land prices will skyrocket in the years to come. This may further curtail their limited access to land resources. Future generations of Sheikhs may be rendered homeless.”Dr Fayyaz Ahmed, Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of Kashmir

‘Kashmir Is Doomed Anyway’

Two successive lockdowns lasting more than a year and the resultant economic havoc have plunged Kashmiris into unprecedented hopelessness and despair. In a new Kashmir fraught with collective anxiety over loss of control over land, burgeoning unemployment, and occupation by non-Kashmiris, this subaltern community is the last priority, leading to their further invisibilisation.

Abandoned and forgotten by anti-India factions and the Indian government alike, the peripheral Sheikh community is a potent symbol of the deep fault lines in Kashmiri society.

That Kashmir’s most revered separatist leaders (who are all at the top of the unsaid caste hierarchy) failed to eliminate these divisions alludes to the exclusionist nature of the Azaadi movement. Simultaneously, their economic plight speaks of the reality of successive pro-India governments, and indeed the Indian Government – especially the incumbent one that professes Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas – itself.

The words of a young, unemployed member of the Sheikh community captures the unspeakable alienation and world-weary pessimism of Kashmiris in general, and this marginalised community in particular:

“Kashmir waise bhi khatam hai. Ab China ke saath jung ho, ya Pakistan ke saath jung ho to hi accha hai. Bomb girayenge, bacha kucha Kashmir bhi khatam kar de to hum Kashmiriyon ki jaan chhoote.”

(Translation: Kashmir is doomed anyway. It is better if there is war with China or with Pakistan. Let them drop bombs and finish off Kashmir altogether. That way, we Kashmiris will be spared further horrors.)

(Nandini Sen is a freelance writer and editor who currently works as a regular contributing (political) writer at Dkoding. She is a History major from Lady Shri Ram College for Women, and holds a Masters in Arabic Language & Literature from the University of Delhi. This is a report and analysis, and the views expressed are the author’s own and that of the interviewees in the story. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)