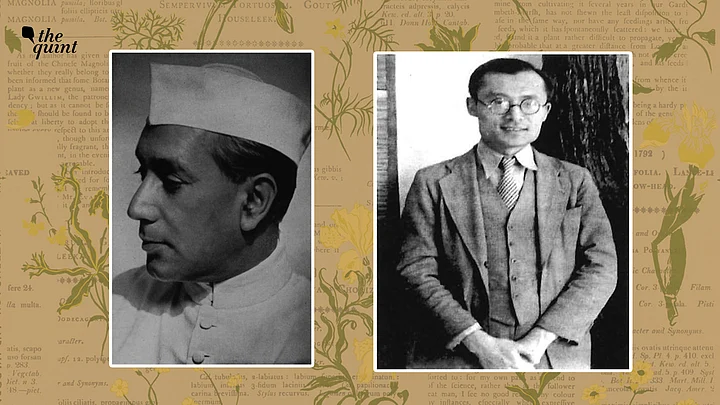

In the history of a medium known for its brevity, Birbal Sahni's (1891–1949) telegram to Hsü Jen (Xu Ren 徐仁; 1910–1992) likely ranks amongst the tersest. Sent on December 20, 1946, its three words – “Hearty Congratulations Doctorate” – meant the world to both sender and recipient. Sahni was among the world's foremost paleobotanists. He had sent these words to his student Hsü, who had recently returned to Beiping (present-day Beijing) after spending two and a half years studying in Sahni's lab at Lucknow University. Hsü thus became, quite possibly, the first Chinese scientist to earn a PhD from an Indian university.

Why This Story of Indian-Chinese Collaboration Matters Today

Within two years, Sahni enticed Hsü back to Lucknow. Appointed a professor and museum curator at Sahni's newly established Institute of Palaeobotany – the first of its kind anywhere in the world – Hsü brought with him specimens of fossilised plant life that he had collected in China.

Sahni’s tragic passing within a week of laying the foundation stone for the Institute’s new building in April 1949 left the fledgling institution in a precarious position. Hsü was among the group of young scientists who provided stability and leadership through this difficult phase, even representing the Institute at gatherings abroad.

After four years in Lucknow, Hsü returned to Beijing, where he helped set up the Institute of Botany at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and carved out a distinguished career.

Reconstructing Sahni and Hsü's collaboration and uncovering the motivations that drove them offers alternate histories of twentieth-century China and India, which have long been mired in a civilisation/realpolitik binary. As a result, the majority of existing scholarship gravitates toward one of two poles: cultural and intellectual history or foreign policy and geopolitics.

A history such as this one, centered on the inter-Asian circulation of experts, scientific knowledge, and materials, also helps decenter Europe and the United States in global histories of science. Barring notable exceptions, histories of the science of China and India, are written either within primarily national contexts or are framed with the West (also Japan, in the case of China) as points of contact and comparison. And yet, as the case of Sahni and Hsü suggests, such a ‘standard model’ paints a clearly incomplete and insufficient picture of mid-century science.

Birbal Sahni’s Many Contributions to Science

Birbal Sahni is a well-known figure in the history of paleobotany and Indian science. Sahni was born on November 14, 1891 in Bhera in West Punjab (present-day Pakistan) to a prominent Punjabi family. His father Ruchiram Sahni would go on to serve as a professor of Chemistry at Government College, Lahore.

His amateur scientist grandfather headed a flourishing banking business in Dera Ismail Khan. Sahni was first introduced to Botany as a student at Government College, Lahore, and he graduated with a BSc. from Punjab University in 1911. He then proceeded to Cambridge University and enrolled for the Tripos at Emmanuel College. He earned a BSc in 1914 and stayed at the University for much of the rest of the decade. It was during these years that he met and was influenced by the geologist and botanist Albert Charles Seward (1863–1941), who instilled in him a lifelong fascination for fossilized plants.

After earning a DSc from the University of London in 1919, Sahni returned to India and held brief appointments at Benares Hindu University and Panjab University before taking up a professorship in Botany at the University of Lucknow in 1921. He remained in Lucknow for the rest of his life.

At Lucknow University, Sahni pursued a rigorous research and teaching agenda that made him among the foremost paleobotanists of his age. Among Sahni's institutional contributions was the world's first research institute dedicated to the study of paleobotany. Known today as the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences, its foundation stone was laid on April 3, 1949, a week before Sahni died.

Silence Around Sahni’s Chinese Connections

Although Sahni's biographies devote extensive space to describe his intellectual connections with scientists in Europe and the United States, they are, with one lone exception, silent about his connections with Chinese scientists.

And yet, Sahni's contacts with Chinese scientists far predated his taking Hsü on as a student. But most of these contacts had been snapped by the late 1930s. In April 1938, Sahni drafted a letter to the Bureau of International Exchange of the Chinese Ministry of Education, explaining that “[o]wing to the war in China I have, unfortunately, got out of touch with all my colleagues working in Botany, Geology and Paleobotany.” He went on to list several prominent Chinese scientists in the hopes that the Bureau might help him reestablish contact.

Sahni and his Chinese interlocutors were a cosmopolitan bunch, frequently in different parts of the world, and their letters and postcards trace global circuits that connected Lucknow, Beiping (Beijing), and Nanking (Nanjing) to Stockholm, Cambridge (UK), and Berkeley.

Although the letters between Sahni and his Chinese colleagues ordinarily focused on research-related topics, they frequently also veered into contemporary affairs, suggesting sensitivity to larger political events.

Sahni’s Most Significant Chinese Correspondent

Sahni's most enduring and significant correspondent – at least for our purposes – was CY Chang, with whom he exchanged letters as early as 1930. One of China's premier botanists, Chang was then on a two-year visit to Europe, splitting his time between the Universities of Leeds and Basel.

After corresponding for a decade and a half, the two finally met in late 1945, when Sahni hosted Chang in Lucknow for a few days. Chang was then en route to the United States and, as was the norm in those days, had broken his journey in Calcutta to change ships.

His Calcutta sojourn eventually lasted twenty days, during which time he along with other Chinese scientists visited botanical labs and other scientific institutions, including PC Mahalanobis' Indian Statistical Institute. Impressed, Chang wrote to Sahni, “India is far more advanced than we in science and technology and we have a great deal to learn from her. I sincerely hope that the good contact between us made in war will be maintained in future.”

One beneficiary of the good contact that Chang celebrated was Hsü Jen. It was Chang who had introduced Hsü to Sahni in the early 1940s and recommended that he work in Sahni's lab. In a letter written after Hsü's arrival in Lucknow, Chang thanked Sahni for helping Hsü, “for in helping him you are helping China to get started in paleobotanical researches…There is not the slightest doubt that he is getting more profit from you than he could get from any European or American scientist.”

Hsü Jen’s Journey from China to Lucknow and Back

Hsü Jen was born in 1910 into a family of merchants and officials in the city of Wuhu (芜湖) in Anhui province. By the time he entered his teens, the family's fortunes had begun to suffer.

A good student, he entered Tsinghua in 1929 and was inspired by the botanist C.Y. Chang to study science. After graduating with a degree in Botany in 1933, he served as a teaching assistant at Peking University's Biology Department from 1933 to 1938. It was during these years that he began to undertake research in paleobotany. In 1937, he moved with the University as it joined with Tsinghua and Nankai to form Southwest Associated University (西南联合大学), first in Changsha and then in Kunming.

During 1938–1939, he was a research fellow in Botany, funded by the British Boxer Indemnity Fund, and from 1939 to 1943 he taught as an associate professor at Yunnan University in Kunming.

It was around this time that he established contact with Sahni, eventually joining him in Lucknow in January 1944. Hsü received his doctorate in 1946 and spent two years as an associate professor at Peking University before returning to Lucknow in 1948 to take on a professorship at the newly established Institute of Palaeobotany.

Aside from Sahni, he was the only other full professor at the Institute. Hsü returned to China in early 1952, serving initially as a researcher in the Ministry of Geology. In 1959, he helped set up the Institute of Botany at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and moved there permanently in 1962.

New Ways to Think About Pan-Asianism Amidst the World at War

Sahni and Hsü's story offers new ways to think about Pan-Asianism. A focus on scientists and their activities provides an instance where the practice of science – carried out by scientists pursuing primarily scientific questions – also produced a form of Pan-Asianism.

In addition to networks of scientists, the Sahni- Hsü story is also about the circulation of palaeobotanic specimens. Hsü and Sahni were avid trekkers and exchanged specimens of plant fossils collected in their native lands. Following these samples allows us to map a second set of circulations and connections. By studying these samples, which demonstrated variations in geology and plant life north and south of the Himalayas, Hsü and Sahni's were exploring an enduring problem within the discipline of geology: the validity of the then-still-controversial theory of Continental Drift.

This interest in a primordial land yet to be carved up by human hands points to the alternate spatial and geographic imaginaries that exist in synchronous tension with the political realities of empires, colonies, nation states, and the world at war.

(Excerpted from: Arunabh Ghosh. (2021). Trans-Himalayan science in mid-twentieth century China and India: Birbal Sahni, Hsü Jen, and a Pan-Asian paleobotany. International Journal of Asian Studies, 1-23.

Download the full article here: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1479591421000292)

Arunabh Ghosh teaches modern Chinese history at Harvard University. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)