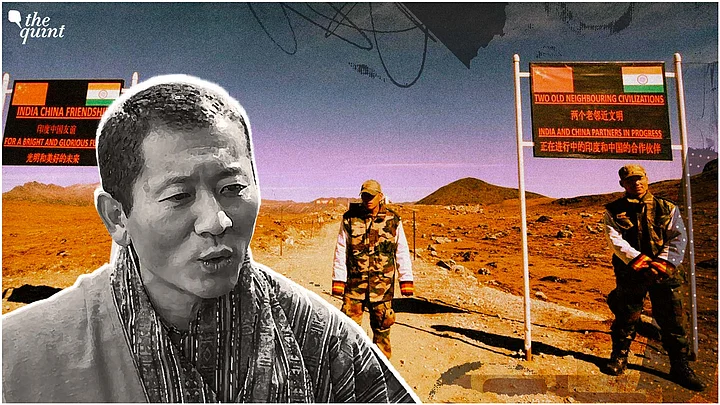

On 28 August 2018, after India and China withdrew their forces from their face-to-face confrontation in Doklam, the Indian media, and some commentators claimed that we had won a famous victory there.

Today, nearly five years later, we are realising how mistaken such assessments were.

In fact, if anything, Doklam marked a defeat which is playing itself out now painfully as Bhutan is readying to concede Chinese demands along its- 470 km disputed border.

This is the message from Bhutan Prime Minister Lotay Tshering’s denial that the Chinese had been building settlements on the Bhutan side of that border. He is quoted as saying that “there is no intrusion as mentioned in the media. This is an international border and we know exactly what belongs to us.”

The denial is baffling, since there is no international border between the two countries and both acknowledge it and have been holding talks over the past three decades to settle their disputes.

How China-Bhutan Ties Will Impact India’s Doklam Issue

Tshering is right though that the China-Bhutan talks are nearing a settlement, and “after one or two meetings, we will probably be able to draw a dividing line.” But that line will be the one that China has decided on. It has already intruded and occupied what it wants. Bhutan will be lucky to get some territory back as part of the overall settlement.

Of more relevance to India is the issue of Doklam which led to the crisis in 2017. Tshering’s statement on Doklam is unexceptional, though the Indian media seems to be fixated on it. He said, “It is not up to Bhutan alone to solve the problem. There are three of us (who will have to decide)… We are ready, as soon as the other parties are ready too, we can discuss.”

This is the exact position India had taken during the 2017 crisis. A Ministry of External Affairs note of 30 June 2017 had said that in their talks on working out a Sino-Indian boundary, the Special Representatives of the two countries had agreed that the “trijunction boundary points between India, China, and third countries will be finalised in consultation with the concerned countries.”

As is well known, the differences over just where the trijunction of the India-China-Bhutan border in the area was the trigger of the crisis. As per the Anglo-China Convention of 1890, the trijunction was at Mount Gipmochi. India had unilaterally decided that it was actually near Batang La some 7-8 km North.

Under the Chinese definition, the Doklam plateau fell within its territory, while the Indian interpretation suggested that Doklam was part of Bhutan. The Bhutanese themselves were not a party to the 1890 treaty but even while the area may not have been important for them, New Delhi considers it vital since its southern Zompelri (Jampheri) ridge provides a platform with a clear view of India’s sensitive jugular, the Siliguri Corridor, that links mainland India to the Northeast.

Why Doklam Matters to India?

Actually, the Indian and Chinese have now thrown open the entire Sikkim-Tibet boundary by agreeing in 2012 that the 1890 Convention needed to be replaced by a Sino-Indian agreement. Discussions on this had arrived only at a “basis of alignment” and not the alignment itself. Presumably, this basis is that of the watershed between the Mochu/Torsa river and the Teesta in Sikkim which was also the basis of the older 1890 Convention.

The problem, as M Taylor Fravel of MIT has noted, was in the 1890 Convention’s belief that the watershed began at Mount Gipmochi. It’s not clear whether the signatories of the Convention which was signed in Kolkata, had surveyed the area and there was no map attached to the treaty. The British maps of 1907 and 1913 showed that the watershed was a bit to the north near Batang La. So, there emerged a gap between the letter of the treaty and its intent.

Almost immediately after the Indian and Chinese troops conducted their 2017 withdrawal which, by the way, could not have been beyond 150 metres on either side, the Chinese began a massive buildup in the northern part of the plateau. Indeed, according to Senior Colonel (retd) Zhu Bo, a well-connected PLA officer, the Doklam crisis resulted in Beijing re-focusing its attention on the entire Sino-Indian border and embarking on a massive build-up that continues to this day.

As part of this, it began to construct a number of Xiaokang (well-off) villages along the LAC and the Sino-Bhutan border. While the villages in relation to the LAC with India were on the Chinese side, in Bhutan, they began to build on what was clearly Bhutanese territory.

The main areas in dispute between China and Bhutan are 269 sq kms on the western border along the Chumbi valley and two northern areas of Jakarlung and Pasamlung valleys measuring 495 sq kms. Since 2020, the Chinese have also raised an additional claim in eastern Bhutan.

Among the first of the Xiaokang villages to be noticed was one called Pangda which was on the banks of the Mochu on the eastern part of Doklam. Blocked from the western approach to the Zompelri ridge by the Indian action of 2017, the Chinese are building roads down to the Torsa Nala that divides north and south Doklam and will eventually reach the ridge from a different direction.

Does India’s Diplomatic Stand Threaten National Security?

In his claim that there is no Chinese intrusion, Tshering has simply ignored evidence that more than a dozen similar villages with supporting roads have come up mainly in the disputed areas in the west, but also in the north, one in the area of Beyul considered sacred in Bhutan.

Thimphu has had little choice in the matter. After the Doklam withdrawal, the Indians simply washed their hands off the issue. Testifying before the Standing Committee of Parliament in early 2018, senior Ministry of External Affairs officials said that all India was concerned with was the immediate area near Doka La where the face-off had occurred. What happens in the rest of Doklam, was something that “is a matter for China and Bhutan to sort out.”

Again, the memory of the Indian media is short and they seem to have forgotten that in the next two years—2018 and 2019—India and China had a lovefest of sorts. Informal summits between their two leaders in Wuhan and Chennai suggested that their relationship had now converged into a new area of friendship.

But the very next year, 2020, China pulled the rug from India’s feet by blockading six places in eastern Ladakh and massing an army near the border. The view from Thimphu could not have been a comfortable one.

In 2020, the Chinese rubbed in their point by reviving their claim to a part of eastern Bhutan that had been dormant and had not even figured in their border talks. Suitably chastened, Thimphu resumed border negotiations that had been on hold since 2017.

What Is the Way Forward for India-Bhutan-China Trijunction?

The 10th round of their expert group talks took place in Kunming in April 2021, and in October of same year, the two sides signed a Memorandum of Understanding on a Three-Step Roadmap “to expedite boundary negotiations.”

In January this year, the two sides met for the 11th round again in Kunming and agreed to “push forward” the three-step roadmap and working out the conditions for convening the 25th round of their border talks, (the 24th round had taken place in 2016).

And now Prime Minister Tshering says that they are just a round or two away from arriving at a final settlement. India can take some comfort in the fact that the issue of the trijunction will formally remain open because it requires the concurrence of all three countries. But in reality, the Chinese will be controlling Doklam.

(The writer is a Distinguished Fellow, Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed are the author's own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for his reported views.)