On the morning of 31 August, nine new judges of the Supreme Court (SC) of India were sworn in. These appointments have finally filled all but one of the vacancies at the court, which was operating at a significantly reduced capacity for months, as against its sanctioned strength of 34.

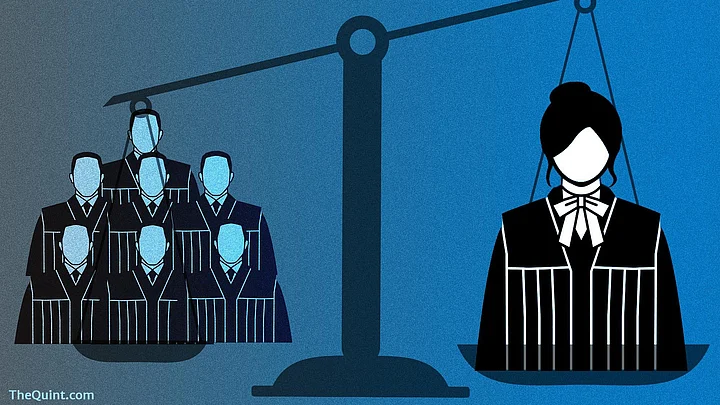

The list of nine new judges has been widely celebrated for including three women Judges – Justices Hima Kohli, BV Nagarathna and Bela Trivedi. Their swearing-in provides a major boost to the number of women judges at the Supreme Court, from one (Justice Indira Banerjee) to now four.

And yet that is perhaps precisely why it's not time to celebrate just yet.

It is certainly positive that for the first time in Indian history, three women Judges have been elevated to the SC bench together. Also, India may finally get its first woman Chief Justice of India in 2027 from among these three judges.

However, the fact of the matter is that despite all this, representation of gender and sexuality in the judiciary remains abysmally skewed and fixing it will require a great deal of conscious intervention, at all levels of the legal profession.

After 75 years of Independence, the presence of four women out of 33 is too little, too late, and grossly insufficient. It is even more unfortunate to note that all the four Judges belong to upper castes and there is no woman judge from a Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe at the Supreme Court.

The numbers are stark and tell a story in themselves. According to the Tata Trusts' India Justice Report 2020, 30 percent of judges in the lower courts of India are women. This reduces to 12 percent of sitting judges in the high courts. Which is also approximately the percentage of women judges at the Supreme Court now, thanks to the new appointments. There is one judge from a Scheduled Caste, and one from a Scheduled Tribe, both of whom are male.

The effects of this kind of a lack of representation and diversity can be dangerous for an institution like the judiciary, which needs to have the public's trust.

The power that is wielded by a judge is capable of touching upon every crucial aspect of an individual’s life. In order for the public to trust the judgments delivered by a judge, a certain legitimacy must be conferred upon the judicial institution.

Breaking the mould of elitism and privilege that currently plagues the Indian judicial system, therefore, is essential if one wants to counter the impression and tacit acceptance that it is the preserve of upper-caste men, and that if you're not one of them, it is not likely that you will be heard or considered.

Improving Decision-Making and Justice Delivery

Decision-making also suffers when various groups are underrepresented in the judiciary as it fails to account for the lived experiences of those whose issues are being adjudicated upon.

A judge who belongs to an underrepresented community has the ability to bring to the table their own unique perspective regarding an issue and educate their colleagues as well.

This perspective can offer a much-needed counter to the dominant viewpoints that so often govern such decisions and, therefore, ensure that their dominance does not overwhelm or suppress the voice of the under-represented. This in turn ensures that a holistic decision can be taken that does not end up perpetuating stereotypes and discrimination.

Take, for instance, the trajectory of the SC in making decisions with regard to the cases of rape and sexual harassment.

In the infamous 1978 Mathura case, the SC disregarded the allegations of gang rape on the ground that the survivor was “habituated to sexual intercourse” and that her passive submission amounted to consent.

This was an atrocious decision which cemented the demonisation of a sexually active woman and refused to account for her agency to say “no”. To this date, this mentality is replicated in certain decisions of lower courts and even high courts from time to time.

Fortunately, the SC moved on from their regrettable decision in the Mathura case to seemingly progressive decisions that were meant for the protection and upliftment of women.

The only catch, however, was that this protection and upliftment could only be implemented within the sphere of patriarchy and by men themselves.

Decisions such as the 2006 case of Om Prakash vs State of UP or the 2013 case of Deepak Gulati vs State of Haryana, paint the picture of a rape survivor as a helpless woman whose honour is defiled and soul is degraded as a consequence of such an act.

They view rape as a deficiency in the survivor herself, and this propagates the idea of a woman whose virtue is more valuable than her independent identity. Instead of empowering women, these decisions infantilise them and relegate them to a stature wherein they must be shielded for their own good.

With greater representation and diversity, such decisions which actually further discrimination, can be circumvented.

Additionally, an inclusive judiciary will also encourage female litigants to knock on the doors of the courts for proper redressal of their problems which arise as a result of our patriarchal society, such as cases of domestic violence or sexual harassment.

While it is no doubt true that even women judges may be capable of regressive stands on these matters, the current domination of the scene by men certainly does not help engender trust.

The knowledge of a woman suffering from domestic violence that she will be heard by those who occupy a similar standing will invariably strengthen her conviction and faith in the judicial institution; this is something which the Indian judiciary currently lacks.

Another positive would be that if an unrepresented or under-represented individual sees a person from their community at the top of the ladder, it would only serve as an inspirational factor that may motivate other members of that community to work toward climbing up that ladder as well.

Don't Fall for the 'Merit' Trap

However, when it comes to positions of power in any profession that require technical knowledge, the argument that is advanced is that a person of greater caliber is more deserving of the job, duty, or promotion.

As practical as that sounds, this argument fails to acknowledge the systemic bias and inequality in place which automatically favours an upper-caste Hindu straight male and ensures his reach to the top, and disregards those individuals who fall outside the four corners of this identity.

Therefore, when the question arises as to why the ratio of women to men is so dismal, one needs to realise that the gatekeeping begins the moment a female child is born and inevitably constructs hurdles meant to impede her rise to the top.

Do not also forget that the power to elevate individuals to the higher judiciary is concentrated in the opaque decisions of the Collegium of the Supreme Court, which has of course been dominated almost entirely by upper-caste men.

Merit cannot therefore strictly be a metric for elevation as it assumes that men and women begin at the same starting point and come across the same obstructions in their path to the Supreme Court.

As mentioned earlier, the numbers are extremely stark, especially in the higher judiciary where the percentage of women judges is barely 12 percent. This is clearly disproportionate to the population of women in the country.

In a recent piece for Article 14, Shruti Sundar Ray analysed this obscene skew in more detail. One of the key observations she makes is that the number of women advocates who take up litigation remains extremely low, which in turn reduces the pool from which judges of the higher judiciary could be selected. This is despite there being greater parity these days between men and women entering law schools across the country.

The reasons for the lack of women in litigation are myriad, but the systemic bias and ingrained patriarchy of the system are extremely prominent among these.

Until and unless this is addressed with the aid of awareness, concessions and affirmative action, the root causes for the lack of gender representation in our higher judiciary will continue to fester.

And having merely four women judges in a cohort of 34 at the highest level of our judiciary will continue to be a cause for celebration and not a cause for shame, which is what it actually is.

The late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg had famously stated that whenever she was asked about when there would be enough women in the US Supreme Court, she would respond with, “When there are nine”, and her answer would shock people.

Her rationale, of course, was that there had been nine men as supreme court justices and no one had ever raised an eyebrow.

Similarly, if anyone wants to ask when it will be the time to celebrate the elevation of more women judges to the Indian Supreme Court, the answer would have to be “When there are 34”.

(Radhika Roy is an advocate based in Delhi and former Associate Editor at Live Law. This is an opinion piece, and the views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)