(This article is being reposted from The Quint’s archives.)

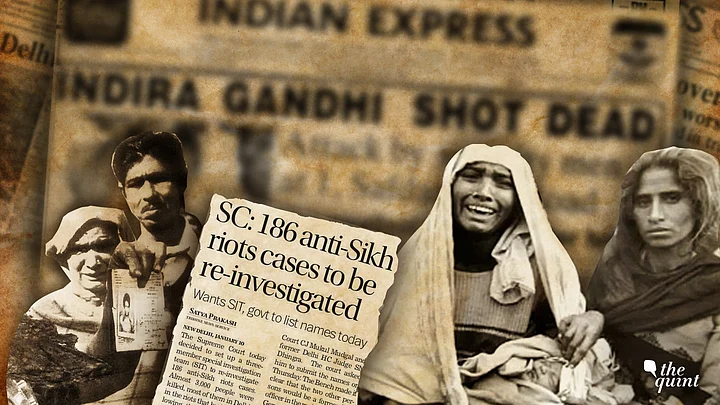

It has been 35 years since the devastating events in India, following the assassination of then Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi on the morning of 31 October 1984. Over four days, thousands were slaughtered by rampaging mobs in the world’s largest democracy. For the action of two Sikhs, the whole Sikh community, barely 2 percent of the population, became targets of revenge attacks.

To date, just one senior Congress leader – Sajjan Kumar – has been brought to justice. Many others though, including police officers named repeatedly in official inquiries, escaped justice.

So what can and should be done? There is an urgent need to address the shocking truth behind the 1984 genocidal massacres and bring about long awaited justice for the victims as well as punishment for the perpetrators. This can only be achieved if there is an acknowledgment at the state, civic and international level of the reprehensible events, their significance, and the importance of finally and fully closing this dreadful chapter of independent India’s story.

As long as the guilty, particularly those in power or public office, continue to evade the rule of law, India’s democracy will continue to be one where justice is hoped and fought for rather than expected.

Will a Truth & Reconciliation Commission Help?

A number of states, including South Africa, Chile, Rwanda and Bosnia, have held independent truth and reconciliation commissions in order to uncover crimes – committed either by past governments or others – in the hope of resolving continuing conflict or injustices.

Priscilla Hayner, a transitional justice expert, has offered a widely drawn upon definition of a truth commission. For her, they are temporary bodies authorised by the state to investigate human rights abuses by the military or other government forces. There is, however, no one model of a commission; their focus and purpose vary according to the cultural, historical and social contexts of the crimes involved.

Previous calls to introduce such a commission in India, whether domestic or international, have been met with resistance.

For example, in 2004 the UK’s Green Party MEPs, Caroline Lucas and Jean Lambert tabled a declaration in the European Parliament for India to set-up a truth commission to investigate 1984. The proposal was supported by the UK-based NGO, the 1984 Genocide Coalition. India’s National Security Adviser J N Dixit responded angrily:

“They will first have to seek our permission if the Commission wants to carry out any investigations. We will never allow such a thing. It is motivated mischief by some people and should be nipped in the bud.”

Yet, a thorough and in-depth independent commission is still required, especially considering the failings of past investigations. This is the only way to ensure that lessons are learnt and implemented, a semblance of justice for the victims is secured and closure achieved to allow the healing process for Indian society as a whole to truly begin.

Any commission’s scope should include:

- The precise nature of the conspiracy to murder Sikhs en masse. When were plans first mooted, hatched and subsequently brought forward? Who was involved, when and why?

- The alleged role played by top government officials state in the planning, execution and subsequent cover-up of the genocidal massacres.

- The on-the-ground organisation and implementation of the pogroms. Specifically, who led the mobs and who provided them with electoral lists, transport, weapons, and the tyres, phosphorous and kerosene used to ‘necklace’ and incinerate victims?

- The role of hospitals that refused to treat the injured victims and who instructed them.

- The rushed disposal and cremation of corpses on the outskirts of Delhi and in mortuaries, including the means of transportation.

- The role of the media and state apparatus in propagating lies to support the notion that Sikhs were a threat to the public.

- The delay in deploying the army, and the lack of effective policing or humanitarian aid.

- Inquiry into the cases of mass rape and of those who instigated rape as a weapon.

- The effect on the survivors, their offspring and communities then and since.

- The pursuit for justice by human rights activists and survivors and what outcomes they would like to see such as jobs, counselling and any further reparations.

Why ‘Riots’ Is Not the Right Term

There needs to be a shift in the language used to describe the events of 1984. The continued use of the phrase ‘anti-Sikh riots’ downplays the magnitude of what occurred, doing an injustice to the victims whilst concealing the true nature and extent of what took place.

The double-speak continues today both in India and the West. When a BBC radio programme in 2013 was confronted with its repeated use of the word ‘riot’ to describe 1984, they responded by saying that they saw it as a ‘neutral’ term.

The current narrative, in both academic and in common parlance, continues to downplay the massacres and their ongoing consequences. This trivialisation has unfortunately passed on to the new generation. Journalist Hartosh Singh Bal notes that the new generation of liberals have “refused to engage with the reality of what happened in 1984. This particular form of blindness leads them to believe that the Congress could not have orchestrated such terrible events, because it does not stand for such atrocities.”

By continuing to refer to the events as ‘riots’, there can be no proper recognition of the nature of the crime and the need to deal appropriately with its perpetrators and survivors.

What is unique in the case of 1984 is the continued lack of recognition and acceptance, including internationally, of the leading role of the Congress Party’s leaders in the conspiracy.

It is this cancer of unaccountability that sets 1984 apart from previous genocidal episodes that came before. Amongst those international bodies entrusted to recognise, investigate and prosecute genocidal crimes, such as the United Nations and the International Criminal Court, 1984 has never figured, although two victims did manage to testify before the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in 2014.

In the subsequent thirty years, there have been a number of genocidal massacres in India including at Hashimpura (1987), Bhagalpur (1989), Mumbai (1992), Sopore (1993), Hyderabad (1990), Coimbatore (1998), Gujarat (2002), Kokrajhar (2012) and Muzaffarnagar (2013). Part of the problem lies in the Indian Penal Code. Although India remains a signatory to the 1951 Geneva Convention on Genocide, and is legally obliged to implement a specific law on all forms of genocide ensuring perpetrators are punished, this is something that does not feature in India’s main criminal code.

In April 2017, Canada’s Ontario government passed a motion describing 1984 as a genocide. In response, Indian External Affairs Ministry spokesperson at that time, Gopal Baglay, described it as ‘misguided’ and the then defence minister, Arun Jaitley, said the language used in the motion was ‘unreal and exaggerated’.

Thus, the introduction of a proper legal framework and laws on genocide and communal pogroms are clearly necessary and desperately required. Without them, the search for justice is severely hampered.’

An End to Impunity

In a nation where the rich and powerful have the means to pervert and evade justice, there can be no closure for the victims. Enough evidence exists to prosecute the perpetrators despite the corruption and dysfunction that have blighted the commissions, committees and inquiries.

Judge Dhingra, who oversaw one of the cases in court (State v Ram Pal Saroj), commented on the failure to deliver justice, “A system which permits the legitimised violence and criminals through the instrumentalities of the state to stifle the investigation cannot be relied upon to dispense basic justice uniformly to the people.’

Civil rights activists and legal reformers within India require global support on order to tip the scale in favour of the victims.

When it comes to genocide there are never two equal sides, so one cannot adopt a position of neutrality. In the words of Auschwitz survivor and Nobel Laureate Elie Wiesel, “We must always take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor, never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor, never the tormented. To remain silent and indifferent is the greatest sin of all.”

In July 2015, world leaders came to the Bosnian town of Srebrenica to recognise the genocide, twenty years on, of 8,000 Muslims by Bosnian-Serb forces. In 1984, thousands had been killed, raped, traumatised and displaced from their homes. The lives of the survivors, their children and of the generations to come have been irrevocably impacted.

It is time for India and the world to take a similar stand. To this day more than ninety-nine percent of the killers remain free.

(Pav Singh is a Britain-based journalist and author of ‘1984: India’s Guilty Secret’, published by Rupa. This is an opinion piece and the views expressed above are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses, nor is responsible for them.)