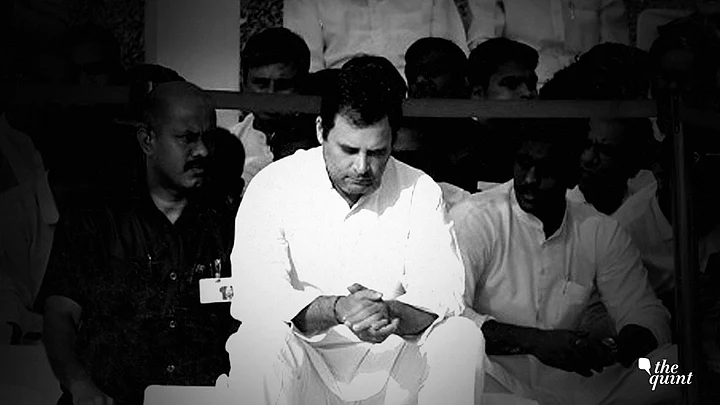

Rahul Gandhi, with his resignation letter on Wednesday, 3 June, has made it quite clear that he will no longer serve as the President of the Congress party. It is very likely that neither the former President Sonia Gandhi nor the General Secretary Priyanka Gandhi Vadra will take up the mantle. After 20 years, the Congress party will no longer be led by a member of the Nehru-Gandhi family.

Although they were at its helm, neither Sonia Gandhi nor Rahul Gandhi exercised complete control over the Party. As the cliche goes, they were the glue that held together the Congress. Their presence at the top helped manage the ideological and the factional differences within the Party. With the family no longer in charge, at least not officially, several fault lines within the Party are likely to become sharper in the following days.

Left vs Right

Since its inception, the Congress has brought together diverse ideological strands, with socialists, economic conservatives, Hindu nationalists and liberals in its ranks. However, a few periods in history saw certain strands become more dominant than the others.

The socialist segment of the party became prominent under Jawaharlal Nehru and the early part of Indira Gandhi’s tenure. But the right wing, both social conservatives and free market advocates, gained precedence under Rajiv Gandhi in the 1980s and PV Narasimha Rao in the early 1990s. Leaders like Arun Nehru, who wielded considerable power, were known to be close to the Hindu right as well.

The economic reforms of 1991 sealed the centrality of free market economics in the Congress’ economic policy but the Babri Masjid’s demolition reflected the right wing’s hold over the party.

Under the leadership of Sonia Gandhi, especially during Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s first term, the Congress stood for a nuanced mix of economic reforms and welfare schemes. In this period, Sonia Gandhi also ended the Congress’ tryst with the Hindu right which took place under Rajiv Gandhi and Narasimha Rao, and brought the party back to Nehruvian secularism.

After the Congress’ dismal performance in the 2014 and 2019 Lok Sabha elections, one section feels that the Party is paying the price for the alleged “alienation of Hindus” under Sonia Gandhi.

The same section also accuses Sonia Gandhi and Rahul Gandhi of being excessively dependent on “leftists”, which has alienated the middle class and corporates as well. Some of the pet targets of this section are former Union Ministers Jairam Ramesh and Mani Shankar Aiyar, and non-political figures who they see as the Gandhis’ advisers, such as social activist Aruna Roy.

Many of the recent polemics are aimed at the former JNU Students’ Union President Sandeep Singh, who is originally from the left-wing All India Students’ Association and but worked closely with Rahul Gandhi’s office and is now with Priyanka Gandhi’s team.

The anti-left wing brigade in the Congress blame Congress’ “leftists” for Rahul Gandhi’s visit to JNU during the 2016 sedition controversy. According to them, this gave the BJP the chance to present Rahul as being in cahoots with the so-called “tukde tukde gang”.

They also blame the Congress’ “leftists” for certain promises in the Party’s 2019 manifesto, such as the proposal to prevent misuse of sedition laws as well as the proposal to review AFSPA.

This section now feels that there is a need to “purge” the “Leftists” from the Congress.

There is a counter perspective to this. Several sections within the Congress, many of which worked closely with Rahul Gandhi, feel that there will now be an attempt to carry out a right-wing takeover of the Congress.

On Thursday, 4 July, a day after Rahul Gandhi’s resignation letter became public, the scion of the Gandhi family arrived in Mumbai for the hearing of a defamation case filed against him for his remarks about the RSS. Some Congress supporters and the Party’s social media team trended the hashtag #RSSvsIndia. Even in his letter, he focused a great deal on the need to continue the fight against the RSS. So, in some ways, the trend stemmed from what he had written.

This can also be seen as an attempt to keep the Congress on the ‘anti-right wing’ path and prevent it from returning to its state in the 1980s and the 1990s.

The Congress is pervaded by the fear that any attempt to dilute the anti-right position it has maintained will compel minorities to shift their allegiance to regional parties or to ones like Asaduddin Owaisi’s AIMIM. Had it not been for the support of minorities, the Congress might have fared even more poorly in the Lok Sabha elections.

Old Guard vs Youth

The second divide, which may intensify after Rahul Gandhi’s exit, is the tussle between the Congress’ Old Guard and the young leaders. The Quint reported on Wednesday, 3 July, that the real story behind Rahul Gandhi’s resignation is his desire to get senior leaders to quit the Congress Working Committee (CWC), the apex decision making body of the Congress, in order to carry out a complete overhaul of the party.

However, the Old Guard is unlikely to give up easy. For the time being, their power has increased. As per the Congress’ constitution, after Gandhi’s resignation, the senior-most general secretary will hold office as the party president. This makes 90-year-old Motilal Vora the Party’s incharge. The next step as per the Party’s constitution is for the CWC to appoint a provisional president until elections are held for the president’s post.

The election can take months and in effect, give charge of the party to the CWC-appointed provisional president. Hence, instead of a dissolution of the CWC, as was hoped for by Gandhi’s supporters, the body might end up calling the shots for subsequent months, which includes the crucial state elections in Maharashtra and Haryana which are due in October.

It’s not only Rahul Gandhi and his close supporters, but also several young party functionaries who have become increasingly impatient with the Old Guard’s unwillingness to concede power. This extends to state units as well. The tussle between Ashok Gehlot and Sachin Pilot in Rajasthan, and between Captain Amarinder Singh and Navjot Singh Sidhu in Punjab is well known. The same can be seen in Kerala, where many young leaders from a Youth Congress background accused senior leaders of giving too much space to Congress allies like IUML and Kerala Congress.

In particular, the Party’s decision to make Gehlot the chief minister of Rajasthan instead of Pilot, is said to have sent the wrong signal to youth leaders. Many of them say that the position rightfully belonged to Pilot, who had worked extremely hard as the Rajasthan Congress chief over the previous five years.

“If Congress went with the PCC chief as chief minister in both MP and Chhattisgarh (Kamal Nath and Bhupesh Baghel), then why not Rajasthan? Why were different standards applied?” said a Youth Congress leader, on the condition of anonymity.

On the other hand, the explanation given by the Old Guard is that the power of young leaders is “overhyped” as most of them, like Pilot, Jyotiraditya Scindia, Milind Deora and others, belong to political families.

Regional Divisions

As Congress looks for its new president, a very real dilemma it has to overcome will be to balance regional differences. The dilemma stems from the fact that 46 out of 52 Congress MPs, a little less than 90 percent, come from non Hindi-speaking states. However, the Party cannot aim to revive at the national level unless it strengthens its hold in Hindi-speaking states, which account for 225 out of 543 Lok Sabha seats.

The Gandhis had a pan-Indian appeal and both Rahul Gandhi and Sonia Gandhi have won elections in the north as well as the south.

Now the dilemma for the Congress is whether to give the top position to someone from states like Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Punjab, which supported it in the Lok Sabha elections, or to prioritise its revival in the Hindi heartland.

There is another aspect to this. Several surveys showed that Rahul Gandhi is more popular than Narendra Modi in southern states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu, despite being way behind in most other states. If Gandhi is replaced by a leader like Sushil Kumar Shinde or Gehlot, there is a possibility that it could cost the party their place in the south, where Rahul Gandhi can still sway votes. On the other hand, if a leader from the south takes over, there is a possibility that it could harm the Congress in the Hindi heartland even more.

Factionalism

In the past, Sonia Gandhi or Rahul Gandhi’s presence at the top helped to contain factional rivalries in the Congress. A good example of this is the tussle after the Congress’ victory in the Assembly elections in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh last year.

The Party won the three states without declaring a CM candidate. Rahul Gandhi personally met all the claimants for the CM’s post and arrived at a workable solution.

With Gandhi no longer at the helm, factional feuds are likely to get exacerbate. Some of the key tussles are:

- Rajasthan: Ashok Gehlot vs Sachin Pilot

- Madhya Pradesh: Kamal Nath vs Jyotiraditya Scindia vs Digvijaya Singh vs Arun Yadav

- Kerala: “I” group led by Ramesh Chennithala vs “A” group led by Oommen Chandy and AK Antony

- Karnataka: Siddaramaiah vs G Parameshwara

- Punjab: Captain Amarinder Singh and Sunil Jakhar vs Partap Singh Bajwa and Navjot Singh Sidhu

- Haryana: Bhupinder Singh Hooda and Deepender Hooda vs Kumari Selja, Randeep Surjewala, Ashok Tanwar and Kiran Chaudhary

- Delhi: Sheila Dikshit vs Ajay Maken

It is quite possible that rival faction leaders may use the vacuum at the top to settle scores with one another.

The need to balance these four fault lines may shape the path the Congress treads on from this point onwards. The choices it makes will shape both its leadership and its narrative and decide whether it is capable of challenging the BJP at the national level.