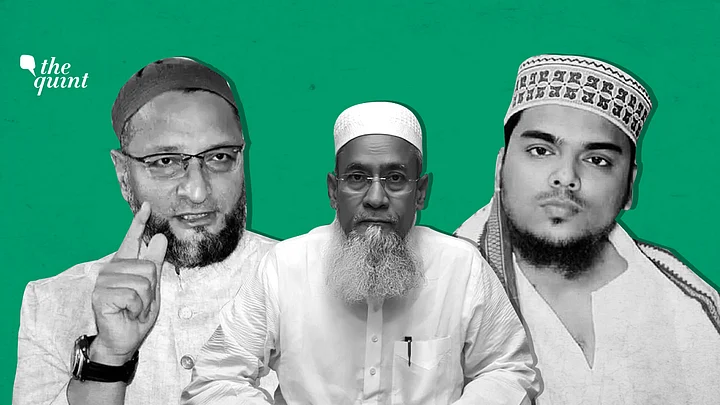

The meeting of All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM) President Asaduddin Owaisi with Pirzada Abbas Siddiqui of Furfura Sharif in the first weekend of 2021 has set in motion an interesting chain of events.

After the meeting with Siddiqui, the AIMIM president told the media, "We will work with Abbas Siddiqui. We will work behind him and support whatever decision he takes.”

On Monday, 4 January, a Trinamool Congress (TMC) minister and one of the party’s prominent Muslim faces, Siddiqullah Chowdhury, slammed Owaisi and Siddiqui, accusing them of working at the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) behest.

“The people of Bengal will not subscribe to the communal agenda of either the BJP or the Owaisi-Siddiqui duo,” he told The Federal.

Chowdhury also compared Siddiqui and Owaisi to the Muslim League and the BJP to the Hindu Mahasabha of pre-partition days.

Owaisi is presently trying to carve out space for greater Muslim representation and an alternative to 'secular' parties nationally and in several states as well. After the AIMIM's success in the 2020 Bihar Assembly elections, West Bengal is one of the states on his radar.

And in Bengal, two interesting players in the Muslim political sphere are Siddiqullah Chowdhury and Abbas Siddiqui.

Story of Two Prominent Clerics

Both of them are among Bengal's most prominent clerics. Chowdhury is an alumnus of Darul Uloom Deoband and state chief of the seminary's political wing – the Jamiat Ulema-i-Hind, which controls a wide network of mosques and nearly 1,000 madrasas across Bengal.

Siddiqui is the Pirzada of the Furfura Sharif Dargah, which also controls a large number of educational institutions, charitable establishments, orphanages and health facilities, giving it a great deal of influence among Muslims and poorer Hindus in districts like Hooghly, North and South 24 Parganas and Burdwan.

Though from different doctrinal persuasions within Sunni Islam – Deobandi and Sufi, respectively – the main difference between the Chowdhury and Siddiqui is political.

In some ways, Siddiqui is today where Chowdhury once was – trying to create a Muslim political alternative in West Bengal.

Past Attempts Towards a Muslim Political Alternative in Bengal

Despite Bengal having a Muslim population of over 25 percent, Muslim political outfits haven't had much political success here.

The romanticised reason given is that ‘due to the trauma of the partition, Bengal kept a distance from both Hindu and Muslim communal politics’. This baggage of partition can also be seen in Siddiqullah’s comparison of Owaisi and Siddiqui with the pre-1947 Muslim League, also reflecting his outfit’s historical rivalry with the League.

But the reason is not that simple.

Part of it was also due to the fact that most of the Muslim elites had migrated to East Pakistan, leaving behind an impoverished and disempowered minority population. This disempowerment reflected in political representation as well.

The Muslim League had won three seats in the 1969 Assembly elections and one seat each in 1972 and 1977. But during the Left Front years, space for Muslim identity politics shrunk to some extent.

It is believed that the Left provided safety to Muslims and ensured communal peace but did little else for the community.

Muslims remained woefully underrepresented in government jobs and at educational institutions. Politically, too, the representation of Muslims in the Assembly and in key positions of the CPM remained much less than their share of the population.

The Sachar committee report exposed the Left’s poor performance vis-a-vis Muslims, and it coincided with a broader disaffection with them among the community, especially due to the Nandigram Movement. And one of the leading figures of that movement was Siddiqullah Chowdhury.

Though he cooperated with the TMC during that movement, he maintained his independence during the party’s first term. He had been associated with the Congress in the late 1980s.

Instead of joining hands with the TMC, Chowdhury formed his own political outfit in 2011 and got some success in the 2013 Panchayat elections. He even contested the 2014 Lok Sabha elections from Basirhat as a candidate of Badruddin Ajmal's AIUDF but got only two percent votes.

He continued to be a measured critic of the Banerjee government, praising her and slamming her on a case-to-case basis.

However, before the 2016 Assembly elections, Banerjee made Siddiqullah join hands with the TMC. She understood that the Jamiat controls a 7-8 percent base across Bengal, which would prove to be useful for the TMC – and it did as the party won a lion's chunk of Muslim votes except in the Congress strongholds of Central and North Bengal.

So, while the first experiment for a Muslim alternative ended in the early 1980s due to the Left Front's denial of space, the second major experiment ended with TMC's appropriation of Siddiqullah Chowdhury.

The third major experiment is now the AIMIM. But the TMC is trying hard to prevent it from gaining a foothold.

AIMIM vs TMC

While the AIMIM had been informally carrying out an outreach over the past one year, it became serious about its prospects in Bengal after winning five seats in the adjacent Seemanchal region of Bihar in the 2020 Assembly elections.

However, even before it could formally begin its efforts, the TMC managed to wean away the AIMIM functionary – Anwar Pasha – and several party workers. Mamata Banerjee has always been possessive about her Muslim vote bank and wary of the AIMIM. Her government has disallowed Owaisi from even holding public functions in the state in the past.

After the Seemanchal success, the AIMIM began making its presence felt in the adjoining districts like Uttar Dinajpur, Maldah and Murshidabad, all of which have a sizable Muslim population of 50 percent and above.

Then, a section of the Imams in North Bengal reportedly held a meeting in Uttar Dinajpur’s Islampur, stressing on the importance of countering "divisive forces" and preventing "division of votes". This was seen as a tacit attack on the AIMIM and endorsement of the TMC.

This is where Siddiqui has come into the picture.

Abbas Siddiqui

The relationship with the TMC has remained uneven, with its top clerics Ibrahim Siddiqui in 2014 and Abbas Siddiqui in 2020, alleging attacks from the TMC. In both cases, the people whose names came up were TMC’s Muslim MLAs – Arabul Islam and Saokat Mollah, respectively.

Abbas Siddiqui's uncle Toha Siddiqui, however, remains a firm TMC backer and has criticised his meeting with Owaisi.

It is not clear whether the AIMIM is projecting Siddiqui as its main face in West Bengal or whether they are going to form an alliance. Siddiqui will announce his plan later this month.

Whatever form the relationship takes, it seems to be a mutually beneficial one for both of them. And the reason for it is: the AIMIM in Bengal is a party without a leader and Siddiqui is an influential religious leader in South Bengal, but one who doesn't have a political party.

In 2019, Siddiqui had said that he plans to form a political party and will contest 45 seats. But he hasn't formed a party so far and is expected to announce his plans later in January.

The Owaisi-Siddiqui duo will have their task cut out, with the TMC having created patronage networks within the Muslim community much more effectively than the Congress in other states or the Left Front in Bengal.

However, the TMC, too, faces certain drawbacks. Like the Left, it is being criticised for not doing enough to address the structural backwardness of the community, particularly in terms of employment.

Though the number of Muslim MLAs has increased, there are regional variations in the representation that the TMC has provided. For instance, two out of its three Muslim Cabinet ministers are from Kolkata – Firhad Hakim and Ahmed Javed Khan. The other Cabinet Minister, Abdur Razzak Mollah, is from South 24 Parganas. Muslim dominated North and Central Bengal districts are underrepresented.

It is precisely this underrepresentation and neglect by secular parties that had helped the AIMIM make inroads in Seemanchal. But with the prospect of the BJP coming to power also looming in the minds of Muslim voters, it remains to be seen how the search for a Muslim alternative pans out.