(On 16 March, President Ram Nath Kovind nominated former Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi to be a member of the Rajya Sabha – to be one of the 12 President’s nominees with special knowledge/practical experience. This article is being republished from The Quint’s archives in light of this development.)

The Supreme Court, on Saturday, 9 November, pronounced its verdict in the long-running Ayodhya title dispute between the three parties — the Sunni Waqf Board, the Nirmohi Akhara and Ram Lalla Virajman.

The court directed that Hindus will get the disputed land subject to conditions. The inner and outer courtyards, the five judge SC-bench said, will be handed over to a Centre-led Trust, and a suitable plot of land measuring 5 acres shall be given to the Sunni Waqf Board.

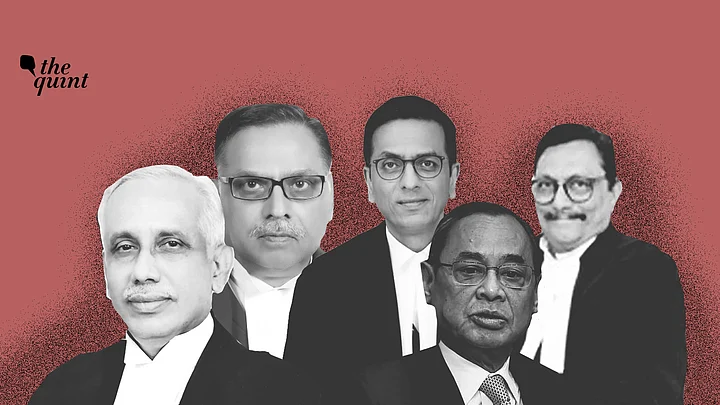

The judges who heard the case were Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi, along with his successor Justice SA Bobde, and Justices Abdul Nazeer, Ashok Bhushan and DY Chandrachud.

In September 2018, in one of former CJI Dipak Misra’s final judgments, the court had held that only three judges were needed to hear the case. However, after CJI Gogoi took over, he surprised everyone by appointing a five-judge Constitution Bench in early January.

Here are the profiles of the five judges whose decision puts to rest a 70-year long case, the legal issues of which were first taken to court back in 1885, and the politics of which redefined India.

1. CJI Ranjan Gogoi

CJI Gogoi initially declined to take up the Ayodhya case in an urgent manner after taking office on 3 October 2018.

Former CJI Dipak Misra had sought to hear the matter –which is an appeal against the Allahabad High Court’s judgment in 2010 which split the disputed land in three between the primary parties – during his own tenure, but was frustrated by delays in the translations of relevant documents and a plea for the case to be heard by a larger bench.

Even CJI Gogoi’s attempts to get the case heard before he retires on 17 November this year looked like they might get frustrated after the judges agreed to let a mediation panel try to help the parties find a settlement. However, when this failed to yield results, the court started hearings on 6 August.

CJI Gogoi, who was formerly Chief Justice of the Punjab & Haryana High Court, was elevated to the Supreme Court on 23 April 2012.

He is known as a strict judge, as could be seen in his conduct of the Ayodhya hearings where he fixed strict time limits for the counsels and maintained order in the midst of the confusion.

His no-nonsense approach can also be seen from his orders on the government’s failure to appoint a Lokpal in 2017, and his contempt notice to retired apex court judge Markandey Katju over his criticisms of the court.

He is also no stranger to controversy, from his driving role in the compilation of the National Register of Citizens in his home state of Assam (he was even asked to recuse himself from one of the matters related to this as) or his involvement in the unprecedented press conference by four senior judges in January 2018.

CJI Gogoi was also accused of sexual harassment by a former court staffer in April this year. He was eventually given a clean chit by an in-house inquiry of Supreme Court judges.

2. Justice SA Bobde

Justice SA Bobde will be the next Chief Justice of India, taking office on 18 November. He was appointed to the Supreme Court on 12 April 2013, following a stint as Chief Justice of the Madhya Pradesh High Court.

Justice Bobde was the one who suggested that the parties consider mediation as an option in this case, following which a three-member mediation panel comprised of retired Supreme Court Justice Kalifulla, Sri Sri Ravi Shankar and mediation expert Sriram Panchu, was appointed to see if the parties could settle the matter.

Justice Bobde had, along with Justice Chelameswar, put a hold on the government’s attempts to link various public and private services with Aadhaar in 2015, and referred the question of the right to privacy to a larger bench. He was one of the nine judges who unanimously affirmed that privacy was a fundamental right and wrote one of the opinions in the case.

He was also one of the three judges who suspended sales of fire crackers in Delhi because of their effect on the environment.

Justice Bobde headed the Supreme Court’s In-House Inquiry Committee that probed the allegations of sexual harassment against CJI Gogoi.

3. Justice DY Chandrachud

Justice DY Chandrachud is also in line to be the Chief Justice of India according to the seniority convention, and could have one of the longest tenures in recent years from 2022 to 2024.

During the Ayodhya hearings, his line of questioning for all the parties has focused more on the technical legal aspects of their claims rather than the historical angles – though he did have some tough questions for the Sunni Waqf Board lawyers over their objections to the ASI report which claimed there were remains of an ancient structure under site of the Babri Masjid.

The son of former CJI YV Chandrachud, he was elevated to the Supreme Court in 2016, and has become one of its most well known figures. His judgment (which forms the plurality opinion) in the right to privacy case in 2017 was lauded for its recognition of the importance of individual liberty, dignity and autonomy. It also expressly overturned his own father’s decision in the ADM Jabalpur case back in the Emergency.

Justice Chandrachud wrote two famous dissents in 2018, in the Aadhaar case and the Bhima Koregaon activists’ arrest case. Calling the Aadhaar Act 2016’s designation by the Centre as a Money Bill a “fraud on the Constitution”, he disagreed with the other four judges and said the whole scheme needed to be scrapped (including for public services) as it violated the right to privacy.

In his dissenting opinion in the Bhima Koregaon case, he held that the prosecution of the activists including Sudha Bhardwaj and Gautam Navlakha were being “persecuted for their views and their voices are sought to be chilled into silence by a criminal prosecution.” He castigated the Pune Police for the way they had handled the case and recommended a court-monitored SIT to probe the allegations against the activists.

Justice Chandrachud also authored the judgment in the Judge Loya case in early 2018, where he held there was no need for a probe into the death of the judge, who died in December 2014 while he was hearing Amit Shah’s discharge application in the Sohrabuddin Sheikh fake encounter case.

4. Justice Ashok Bhushan

Justice Ashok Bhushan’s ‘parent’ high court was the one where the Ayodhya case originated: the Allahabad High Court, where he practiced from 1979 to 2001. He was elevated to the Supreme Court on 13 May 2015, after serving as Chief Justice of the Kerala High Court.

When the five-judge bench for the Ayodhya hearings was initially announced, it included Justices UU Lalit and NV Ramana instead of Justices Bhushan and Nazeer.

However, they recused themselves from the case (in Justice Lalit’s case because he had represented former UP Chief Minister Kalyan Singh in a connected case) and so a fresh bench had to be announced on 29 January.

During the hearings, Justice Bhushan asked the lawyers for all sides searching questions based on the Allahabad High Court judgment, including details of the cross-examination of the witnesses, and how issues of faith are relevant to the legal dispute.

The involvement of deities in this case – Lord Ram (through his idol) and of the Ram Janmabhoomi itself – means faith is a key component of the decision, and was the basis for the high court’s determination that the pride of place of the disputed site would be granted to them.

Justice Ashok Bhushan has been on the bench in a number of high profile cases in recent years, including the challenge to the constitutionality of the Aadhaar scheme and the Delhi vs Centre case.

He wrote a separate but concurring opinion in the Aadhaar case, which dealt with how the right to privacy was not infringed by collection of demographic data, and that there was insufficient evidence to show people were being denied services because of it.

5. Justice Abdul Nazeer

Justice Abdul Nazeer was elevated to the apex court on 17 January 2017, after nealry 14 years as a judge of the Karnataka High Court. He is only the third judge to have been appointed as a judge of the Supreme Court without having served as chief justice of a high court.

During the Ayodhya hearings, he exercised restraint but asked tough questions for all parties, joining Justice Chandrachud in questioning the Muslim parties’ dismissal of the ASI report about the site.

Justice Nazeer had been part of the three judge bench during CJI Misra’s time which heard the request to refer the case to a larger bench. He dissented against the majority ruling there, holding that a five-judge bench was required to hear the Ayodhya case so that it was not bound by some controversial observations in a 1994 judgment of the apex court in the Ismail Faruqui case, which had said that a mosque was not an essential part of the practice of Islam.

The crux of Justice Nazeer’s dissent was that even though the majority held that those observations were not binding, the Allahabad High Court had in fact relied on them in its 2010 decision regarding Ayodhya.

It is unclear if this dissent influenced CJI Gogoi’s decision to have five judges hear the case, but the larger number of judges were able to hear arguments regarding the incorrectness of the high court’s approach.

Justice Nazeer was also part of the minority opinion in the Triple Talaq case in 2017, where he joined with former CJI JS Khehar to say that the court could not pass a ruling on whether the practice was illegal, but it would be stayed for 6 months so that Parliament could pass a law to make it illegal. The majority held that they could strike it down, and did so.

He was also one of the nine judges who upheld the fundamental right to privacy .