"It might have been better If I was not part of the Bench. We all make mistakes. No harm in accepting it."Ranjan Gogoi at book launch according to Bar and Bench

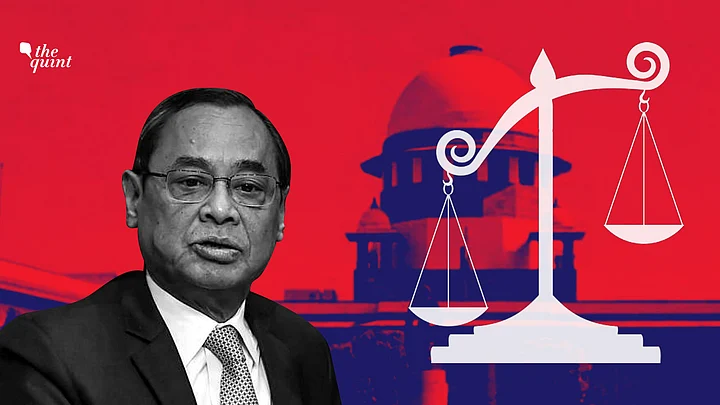

With these three sentences, former Chief Justice of India Ranjan Gogoi brushed off his shocking decision to set up and be part of a special hearing on 20 April 2019 at the Supreme Court to address the allegations of sexual harassment that had just broken in the media against him.

That the current Rajya Sabha MP thinks it just 'might' have been better to not be part of that hearing, where he used the bench to make unfounded counter-allegations of a conspiracy to target him and the judiciary, is perhaps not surprising.

What is surprising, however, is that Gogoi, who was speaking at the launch of his book 'Justice for the Judge' on 8 December, was not pressed about this issue by journalist Rahul Kanwal, who was conducting a question and answer session with him.

And it was not just on this issue that Gogoi was able to evade serious criticism of his tenure.

When asked questions about the many controversies connected to him, from the NRC judgment (before he became CJI) to the handling of the Kashmir cases, he gave answers that deserved further scrutiny, given the vital institution he was part of and the position of power he held.

None was forthcoming – so here are the follow-up questions that Ranjan Gogoi should have been asked at his book launch.

1. How Does Fear for His Reputation Justify Being a Judge in His Own Cause? And Why Remove the Evidence?

According to Gogoi, he was part of the bench that took up the sexual harassment allegations because "45 years of my hard work in Bar and Bench was being spoiled."

"In hindsight, I should not have been a Judge in the Bench," he told Kanwal, before asking, "But, what do you do if your reputation as an upcoming anchor is destroyed?"

With all due respect, this could not have been a consideration for how the Chief Justice of India, the head of the judiciary, which is meant to uphold the law and protect the rule, is supposed to make decisions. When Gogoi sat on the bench that day on 20 April 2019, this was not the same as someone holding a press conference to protect their reputation.

If he had wanted to protect his reputation, he could have easily held a press conference or given proper responses to Scroll, The Wire, Caravan and The Leaflet, which reached out to him in advance of publishing the story about the allegations.

Instead, he used the judicial side of the Supreme Court itself as a platform to defend himself and throw allegations against the complainant.

How can this be termed a mere mistake? Was this not an abuse of the power vested in him as Chief Justice of India?

And more pertinently, why did he remove his name from the record of proceedings of that hearing? Was that not an attempt to hide the abuse of his power as Master of the Roster?

2. Why Isn't There a Proper Mechanism for Sexual Harassment Allegations Against Judges of the Supreme Court?

While defending himself at the book launch, Gogoi argued that the Supreme Court's In-House Procedure for looking into complaints was a good enough way to deal with the allegations.

However, this process is entirely at the discretion of the Chief Justice of India, and follows an ad hoc procedure without any rights or protections for a complainant, and offers no guarantees that the investigation will be headed by a woman.

This means it is not in step with the 2013 law on prevention of sexual harassment of women at the workplace.

A 2014 Supreme Court-directed review of its procedures on sexual harassment at the workplace by veteran senior advocates Fali Nariman and PP Rao had warned of this, and noted that the internal complaints committee set up by the apex court (which complied with the law) could not be used to make allegations against sitting judges.

As a result, they suggested that a new mechanism should be developed as judges of the Supreme Court did not have immunity from the law on sexual harassment – but their suggestions have been ignored by successive CJIs.

All these problems were on full display when a committee headed by Justice SA Bobde (as he was then) was set up to conduct an inquiry (the other two members were Justices Indira Banerjee and Indu Malhotra) into the allegations of sexual harassment against Gogoi.

The complainant was not allowed to have a lawyer present despite the imbalance of power, was not given records of the hearings, and eventually decided to withdraw from the inquiry.

How, therefore, could Gogoi claim that the In-House Procedure was a proper way to address the allegations against him? And why did he say that he 'put his neck out' by asking an In-House Committee headed by Justice Bobde to probe the allegations rather than letting an additional registrar look into them – when there was no question of an additional registrar looking into the matter?

Furthermore, why didn't he set up a proper mechanism to deal with allegations of sexual harassment against judges as advised by the 2014 expert report? (This is not just a question for Gogoi, but other CJIs since March 2014 as well)

3. Why Did He Not Deal With the Human Rights Cases Arising Out of Kashmir Before He Allocated the Matters to Justice Ramana?

Gogoi batted aside a key question raised about his tenure, that he didn't deal with important human rights cases or the Kashmir matters, because of his interest in hearing the Ayodhya case.

As one might recall, he was CJI at the time when the Modi government abrogated Article 370 of the Constitution and reorganised Jammu and Kashmir into two Union Territories (5-6 August 2019).

In response, Gogoi said: "I allocated the Kashmir cases to an alternate bench since Ayodhya was from August 6. I didn't let the Kashmir case hibernate."

While he is right to point out that the cases dealing with (a) the constitutional challenges to the abrogation of Article 370 and the reorganisation of J&K; and (b) the restrictions on internet and movement in J&K were assigned to benches headed by Justice Ramana, this did not happen immediately.

These two cases were only transferred to Justice Ramana on 30 September 2019; till then all the matters coming out of J&K were heard in Gogoi's own court. Among these were several habeas corpus petitions, given the mass detentions of politicians, lawyers, businessmen and other public figures in the erstwhile state.

Hearing habeas corpus petitions, which are a remedy against illegal detention, is a key function of a constitutional court that is supposed to protect fundamental rights.

The problematic way in which these matters were handled by the Supreme Court cannot be fobbed off on other judges.

While hearing a plea by Iltija Mufti, daughter of former J&K chief minister Mehbooba Mufti who was one of the detainees, Gogoi had infamously asked: “Why do you want to move around? It is very cold in Srinagar."

On 30 September 2019, his court dismissed a habeas corpus plea filed on behalf of former chief minister Farooq Abdullah by his friend, the Tamil Nadu politician Vaiko, nineteen days earlier. The court dismissed the plea because on 16 September, a detention order against Abdullah under the J&K Public Safety Act had been passed – a day before the court first heard the petition..

Not only had the court's delay in hearing the matter allowed the government to come up with a post-facto order for detention, the court did not bother to ask how Abdullah had been detained from the night of 4 August till 16 September, ie around six weeks.

A similarly lackadaisical approach was followed in the habeas corpus plea filed for CPI(M) leader MY Tarigami, by his colleague Sitaram Yechury. Instead of inquiring about the detention order against him and looking into its validity, the bench headed by Gogoi instead agreed to let Yechury meet Tarigami while directing him to not indulge in any political activities.

Why didn't CJI Gogoi conduct urgent proper hearings into the habeas corpus matters arising out of Jammu and Kashmir that were heard by him before he allocated the Kashmir cases to Justice Ramana? Why did the court not look into the grounds for detention of political prisoners?

4. While Hearing the Kashmir Cases May Have Been Justice Ramana's Responsibility, What Happened to the Electoral Bonds Petitions?

In late March 2019, with the Lok Sabha elections looming, a Supreme Court bench headed by CJI Gogoi belatedly began hearing the petitions which had been filed in the court challenging the constitutionality of the electoral bonds scheme.

The scheme, first formulated in the Finance Act 2017 and implemented a year later, allowed anonymous purchases of bonds from the State Bank of India which could be given to a political party of one's choice as funding.

Along with the creation of the bonds, the government had also done away with the cap on corporate political funding, as well as numerous disclosure requirements for parties on where they were getting their money from.

After several hearings, the court passed an interim order on 12 April 2019. Although the court did not stay the electoral bonds scheme for the duration of the upcoming elections as had been hoped, it directed all political parties to provide details of the donations received by them including the names of donors by 30 May 2019.

The order utterly failed to engage with the issues raised in the petitions, but at least it indicated that the court was willing to take up the matter after the end of May, as was orally indicated by the judges.

However, CJI Gogoi never listed the case again. In March 2020, he told Times Now editor Navika Kumar in an interview that he didn't even remember the issue.

Why was the electoral bonds matter never listed after 30 May 2019, even though the bench in its interim order had said that "the rival contentions give rise to weighty issues which have a tremendous bearing on the sanctity of the electoral process in the country"? What happened to the in-depth hearing that the order promised?

5. How Was the NRC a "Constitutional Obligation"? Why Was the NRC Process Ordered Even Though its Constitutional Validity Was Referred to a Larger Bench?

Gogoi also defended the 2014 judgment in which a bench of him and Justice Rohinton Nariman (who authored the judgment) held that the National Register of Citizens for Assam needed to be completed.

Over the next few years, he would preside over the benches dealing with implementation of the process for completing the NRC, taking information from the coordinator of the project in a sealed cover, fine-tuning which documents were to be used, and by when the process needed to be wrapped up.

When asked about it by Kanwal, Gogoi replied:

"Who said government wanted NRC hastily? What was correct was not said, and what's not correct was said. NRC is an constitutional obligation and we had to do it."

There are a number of grounds to criticise the court's involvement in the NRC process, including how it impacted the lives of millions without there even being any data on illegal immigration in Assam.

Leaving aside those questions, however, the big one to ask was why the NRC process was initiated by the judges even though the legislative basis for it – which comes from Section 6A of the Citizenship Act, introduced to give effect to the Assam Accord – was under constitutional challenge.

The 2014 judgment by Justices Gogoi and Nariman itself had referred this issue to a larger bench. Not only was this not asked during the book launch, Gogoi was not pressed on his claim that the NRC is a "constitutional obligation".

So why was the NRC ordered to be completed even though it could turn out that the whole process was unconstitutional?

Where does the Constitution of India mandate the creation of an NRC in Assam? How can a process brought in under the Citizenship Act and Rules be termed a constitutional obligation? How could this obligation exist if the constitutional validity of it all was in question?