S Abdul Nazeer retired as a Supreme Court judge on 4 January. Thirty nine days later, on 12 February, he was appointed Governor of Andhra Pradesh.

A slew of questions have been raised in context of his appointment. While some have wondered if there should be a cooling period between retirement and appointment to a gubernatorial position, others have wondered if Justice Nazeer’s judicial legacy somehow contributed to his selection for this post.

Note: Neither of these questions are new or unprecedented. Previously too, when former Chief Justice of India P Sathasivam was appointed Kerala Governor, critics wondered if it was fair and appropriate.

It is difficult to provide answers for such questions. But, in context of the bubbling controversy, it might be pertinent to reflect on Justice Nazeer’s tenure as a Supreme Court judge. Also for the uninitiated, simply:

Who is Justice Nazeer? What were the highlights of his career as an apex court judge?

Justice Nazeer took oath as a judge of the Supreme Court in February 2017. He retired six years later. During the course of his career at the Supreme Court, he:

Upheld Right To Privacy As A Fundamental Right

Perhaps, one of the most celebrated judgments, iconic for its constitutional clarity and reaffirmation of fundamental rights, is the the judgment in the KS Puttaswamy case.

Passed on 24 August 2017, this judgment by a nine-judge bench unanimously upheld right to privacy as a fundamental right enshrined under Article 21 of the Constitution of India.

Describing the Puttaswamy judgment as a right to liberty and a right to dignity judgment along with being a right to privacy judgment, Human Rights Activist Usha Ramanathan had told The Quint the verdict “explains how every person in this country has a right to be who they are. And it also explains how the State cannot control who you are.”

Dissented In The Triple Talaq Case

Perhaps Justice Nazeer’s most prominent dissent, would be his dissent in the Triple Talaq case (again, in 2017).

While the majority verdict in the case held the practice of instantaneous triple talaq (talaq – ul – biddat) to be legally invalid, then Chief Justice of India JS Khehar and Justice Nazeer begged to differ, writing:

“Religion is a matter of faith, and not of logic. It is not open to a court to accept an egalitarian approach, over a practice which constitutes an integral part of religion. The Constitution allows the followers of every religion, to follow their beliefs and religious traditions.”

While this approach may be credited as an attempt to adhere to the principle of secularism, analysts have argued that the dissent elevates personal law to the status of the Constitution, and above all fundamental rights. Writing in his blog, Advocate Gautam Bhatia said:

“It would have fatally undermined the framers’ attempts to frame a secular Constitution, where religion could not become the arbiter of an individual’s civil status and her civil rights, and would, in a single stroke, have set back a long struggle for the rights of basic equality and democracy against the claims of religion.”

Facts of the case aside, a dissenting view is always of consequence. Not merely because it paves the way for correction in the future, in case there has been an error, but also because (as told by Advocate Tanvi Dubey in a previous article for The Quint):

“It tells us that even though the majority judges on a bench hearing a particular case thought a certain way, there is also room for those who disagreed.”

Besides, it is also testimony to a judge’s independence of mind. This display of independence, along with the Puttaswamy verdict, must have been promising indications when Justice Nazeer first came to the apex court in 2017.

So what happened in the later years?

Justice Nazeer sat on several benches and adjudicated several disputes in the later years. The outcome of some of which was concerning as it flew in the face of constitutionality — which had been so strongly upheld in Puttaswamy, or because they displayed a tendency to favour the executive's view.

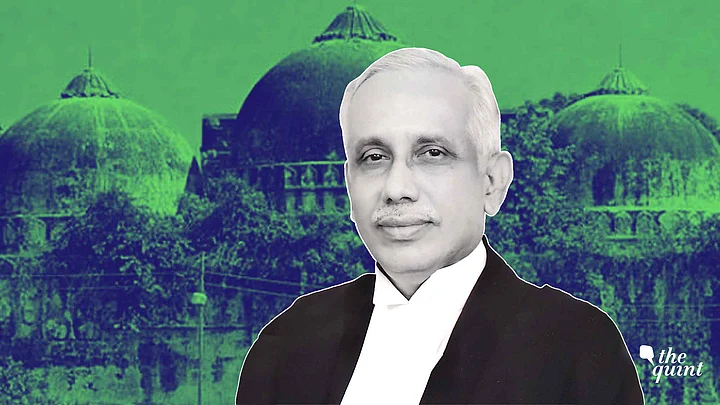

Allowed Construction of Ram Mandir at the Disputed Land

In 2019, Justice Nazeer was part of a five-judge bench which unanimously held that the entire disputed land of 2.77 acres in Ayodhya must be handed over for the construction of Ram Mandir. The Sunni Central Waqf Board, on the other hand, was allotted five acres of alternate land in Ayodhya.

This verdict, which was hailed as a peace-keeping measure of sorts, appears to have discounted the entire bloodied history of the Babri Masjid demolition. It has been criticised as an act of “unequal compromise”.

Legal scholars John Sebastian and Faiza Rahman, argued in The Wire, that by couching the judgment in the “neutrality of the rule of law, many of the brute political factors that underlie its reasoning are pushed into the background.”

They also pointed out that by recognising that the “possession over the inner courtyard was a matter of serious contestation often leading to violence”, the court “effectively put a legal imprimatur upon violence.”

In an article for The Hindu, Advocates Suhrith Parthasarthy and Gautam Bhatia wrote:

“There is a crucial distinction between resolving a dispute on the basis of principle, and achieving “peace” simply by endorsing the existing balance of power — or by not provoking the strong.”

The Babri Masjid demolition and its aftermath is remembered as one of the most devastating chapters of Indian History, in which more than 2,000 people lost their lives.

Upheld Demonetisation Exercise as Lawful

Two days before his retirement, Justice Nazeer passed a verdict upholding the decision by the Union government to demonetise the currency notes of Rs 500 and Rs 1000 denominations.

The judgment, passed by a 4:1 majority, held that the Government of India’s demonetisation notification of 2016 “does not suffer from any flaws in the decision making process”.

Reading out the verdict, one of the other judges on the bench, Justice BR Gavai had also said:

"There has to be great restraint in matters of economic policy. Court cannot supplant the wisdom of executive with its wisdom."

The sole dissenter in this matter, Justice BV Nagrathna, however, pointed out that the demonetisation of all series of currency notes at the instance of the government is far more serious than that of a particular series by the bank. Thus, such an exercise ought to be carried out through a legislation (as opposed to an executive notification, which is what happened).

She also added that “...Parliament which is the fulcrum in our democratic system of governance, must be taken into confidence…Parliament is...a “nation in miniature”; it is the basis for democracy.”

Held That Govt Cannot Be Made Vicariously Liable For Hate Speech By Ministers

The same bench, which gave the demonetisation verdict, by the same 4:1 ratio, also held that a minister’s hate speech cannot be vicariously attributed to the government.

“A statement made by a minister even if traceable to any affairs of the state or for protection of the government cannot be attributed vicariously to the government by invoking the principle of collective responsibility.”

However, again, Justice Nagarathna begged to differ, stating that if a minister indulges in hate speech in his “official capacity”, then such disparaging statements can be vicariously attributed to the government. She justified this by pointing out:

“Hate speech strikes at the foundational values of the Constitution by marking out a society as being unequal. It also violates the fraternity of citizens from diverse backgrounds, which is the sine qua non (an essential condition) of a cohesive society based on plurality and multiculturalism such as in India...”

As pointed out here, Justice Nagarathna’s dissent is pertinent as it comes at a time when hate speech appears to be on an exponential rise, with government figures exhibiting a shocking lack of restraint in TV debates and public meetings. During the hearing of this case, the apex court was also informed by the petitioners that there has been nearly a 500% rise in reported cases of hate speech made by politicians and public functionaries.

Thus, it is hard to make sense of why Justice Nazeer and the others on the bench were unable to see the pressing need for such measures that would compel the government in power to reign its legislators in.

So, Why the Raised Eyebrows?

Of course, a court is a place where diversity of opinion is welcome. Whether a judge chooses to side with the executive in a specific matter or not, is entirely his own discretion.

However, an appointment to such a high government post within days of retirement can be reason for a few raised eyebrows. Pertinently because, even when there is no ulterior motivation at play, it gives the appearance of the government rewarding a select few, and this appearance can be detrimental to the image of a democracy. This is because arguably a democracy survives in the gap between the executive and the judiciary.

At the time of his retirement and without delving too deeply into it, former Chief Justice of India UU Lalit had told a news channel:

“To my mind, having held the position as Chief Justice of the country, perhaps, I think the position as a nominee Member of Rajya Sabha is not the correct idea or as a Governor of a state is again not a correct idea.”

If that is true, then perhaps the same would be true for a Supreme Court judge whose judicial responsibilities were largely at par with the Chief Justice of India. Remember, how the CJI’s verdict, albeit welcome, is inapplicable when it is in the minority? That means, even though he is the master of the roster and the head of the collegium, his own colleagues at the bench can trump his judicial view. So if some ideal can apply to the Chief Justice of India, should it not apply to the others who sat with him?

CJI Lalit did add, however: “That's my personal view. I'm not suggesting that those persons (who took up such posts) are in the wrong.”

(With inputs from NDTV, Livelaw, The Wire and The Hindu.)