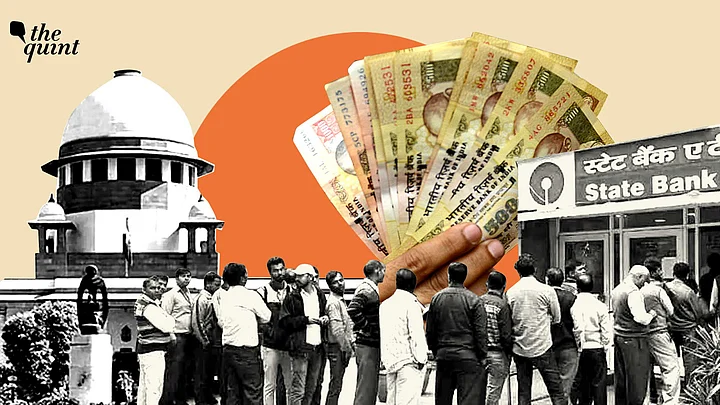

The Supreme Court is slated to pronounce its verdict today (2 January) on a bunch of petitions challenging the BJP-led Union Government’s 2016 move demonetising Rs 500 and Rs 1000 bank notes.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi had claimed that demonetisation would reduce the use of black money and counterfeit cash to fund illegal activity and terrorism, and would increase cashless transactions.

However, media reports of prolonged cash shortages, lengthy currency note exchange queues and significant distress to citizens also surfaced after the move.

In view of this, several petitions were filed and the hearing in the case commenced on 12 October this year.

A Constitutional bench (comprising Justices S Abdul Nazeer, BR Gavai, AS Bopanna, V Ramasubramanian and BV Nagarathna) heard arguments from both sides – and reserved their verdict on 7 December.

So, what is the court expected to answer in its judgment? What have petitioners argued in court? And what has the state contended? We answer.

What is the Court Expected to Answer?

Although it has already been six years since the move and the government’s decision cannot be reversed, the court is expected to rule on the constitutional validity of demonetisation.

The Court, in its verdict, is expected to answer the following questions:

> Does the demonetisation scheme go by the provisions of the Reserve Bank of India Act, 1934?

> Was the scheme implemented in an unreasonable manner which violated the Rights to Equality and Livelihood?

> To what extent can the SC review a scheme relating to the fiscal and economic policy of the government?

Why is the Verdict Important?

Over the course of the hearing the top court had observed that although there was limited scope for judicial review here, it would not sit with folded hands and thus, has the potential to examine the manner in which the decision was taken.

Interestingly, however, when the hearing had just begun on 12 October, the court had questioned the point of hearing the case:

“If the issue is academic, there is no point in wasting the court's time. Should we take this up at this stage after passage of time? We can deal with individual issues,” Justice Nazeer had said, according to LiveLaw.

But, the court changed its stance after Senior Advocate at the Supreme Court and former Union Minister P Chidambaram, appearing for the petitioners argued that although the effects of the decision cannot be undone, the Court “should lay down the law for the future, so that "similar misadventures" are not repeated by the future governments.”

So, What Else Have Petitioners Said in Court? 4 Points

1) The Move’s Objectives Remain Unmet

Chidambaram, contended that the objectives of demonetisation as mentioned by the Government, were “false and could not have been and continues to not be achieved by demonetisation.”

The government had said that the scheme was meant to:

curb circulation of fake currency notes

seize unaccounted wealth or black money

curb activities related to narcotics and terrorism

However, Chidambaram argued that:

> People have come up with new ways to design counterfeit notes, as is revealed by the ones seized by law enforcement agencies

> Black money is not stored as much in cash as in unliquidated assets, and immediately releasing Rs 2000 denominations after demonetisation made it easier to hoard black money in cash

> Highlighting instances where terrorists have been found with counterfeit Rs 2000 notes, he pointed out that such activities continue despite the government’s widely decried move

2) Went Against The RBI Act

The Union Government has claimed that it has the power to demonetise currency under Section 26 (2) of the RBI Act.

However, Chidambaram argued that the provision allows only a specified series of currency to be demonetised, while the 2016 government notification demonetised all series of Rs 500 and Rs 1000 currency notes.

Contextualising this, he brought to the fore examples of the last two times such exercise was carried out in 1946 and 1978, when only a small proportion of the then valid currency notes were taken out of circulation.

3) Due Process Not Followed

How?

> Chidambaram said that according to convention – a move, which can have drastic consequences on the country, must first be recommended by the RBI’s central board and then be deliberated upon by the Parliament

> According to him, neither of these steps were followed. In fact, he said that the the Finance Ministry submitted the draft scheme to the RBI at 5:30 PM on 8 November 2016 and Prime Minister Narendra Modi made the demonetisation announcement at 8 PM the same day

> This left the Central Board with just 2.5 hours to deliberate upon and communicate their decision to the Cabinet

> He further said that the Central Board was neither given adequate notice to consider the move nor given adequate time to apply their minds

4) Govt, RBI Can’t Look Away From Their Assurances

Senior Advocate Shyam Divan, also representing the petitioners, told the court that neither the government nor the RBI should be allowed to ignore the assurances made to the citizens that the window for exchanging old notes would be kept open till March 2017.

“Broadly, the representation was that the end of December was not going to be a hard stop with respect to the exchange of notes," he said.

Divan was appearing on behalf of a petitioner who had left behind Rs 1.62 lakh in cash when he travelled abroad in April 2016 but could not exchange his money when he finally returned to the country in February 2017.

The top court, responding to this, orally observed that the Reserve Bank of India should consider the genuine applications made by persons who missed the deadline for exchanging the demonetised currency notes.

And What Have The State & RBI Said? 4 Points

1) Demonetisation Achieved Digitalisation and Tax Collection

Attorney General Venkataramani, citing data on increase in digital currency usage, the number of PAN cards issued, and the tax received by the government, claimed that the 2016 move was indeed successful.

2) ‘RBI Act Cannot Be Seen In Isolation’

The Attorney general told the court that Section 26 of the RBI Act, under which the Union carried out the demonetisation exercise, could not be seen in isolation, and has to be examined in the context of RBI's role as a Central Bank and the manner in which it exercises its functions.

However, Justice BV Nagarathna pointed out that Section 26 was a Central Banking Function and fell under a Chapter titled the same in the Act.

3) Demonetising Specific Series of Notes Would Lead To Mass Confusion

Responding to the petitioners’ arguments that Section 26 of the RBI act only allowed the government to demonitise notes of a ‘specific’ series and not all of it, the Attorney General argued that the same act also had the words ‘any denomination’ mentioned in it.

“If only a specific series of currency notes could be demonetised, it would lead to mass confusion,” he said.

4) Act Does Not Mention Who Has To Start The Process: RBI

Senior Supreme Court Advocate Jaideep Gupta, representing the RBI, said that it was wrong on the petitioners’ part to argue that a process like demonetisation must be first initiated by the central bank and then deliberated upon by the government.

He asserted that the last two steps in this process, that is, a recommendation by the Reserve Bank, and a decision from the Central Government, were materially complied with.

"Were you consulted?" the bench asked.

"We gave the recommendation," Gupta said.