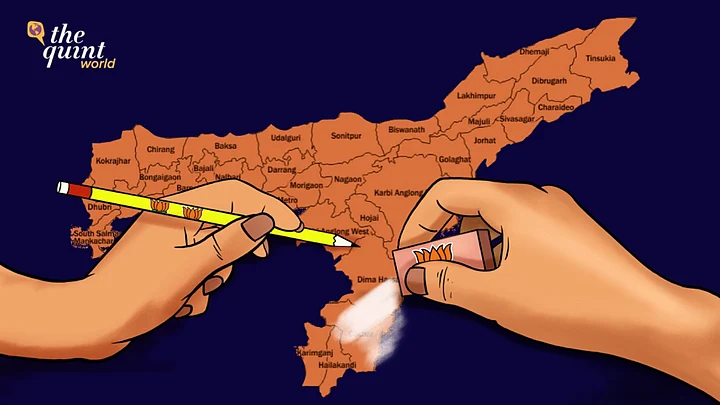

In December last year, Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma ordered the merging of recently forged four administrative districts with their parent districts. The controversial decision ahead of a delimitation exercise raised eyebrows and has led to accusations of “gerrymandering” to consolidate the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) power and weaken the influence of Muslim voters in certain constituencies.

Last year’s delimitation in Jammu and Kashmir generated similar controversy after a delimitation commission approved the addition of six new constituencies in Jammu and only one new constituency in Kashmir, even though the population of Kashmir is substantially larger.

The delimitation exercises in Assam and Jammu and Kashmir seem to be an attempt to weaken the voting power of Muslims. To observers of politics in the United States, the story is all too familiar as the exercises bear similarities to gerrymandering in the states.

In recent years, gerrymandering of Congressional boundaries has given the Republican Party a competitive advantage in elections by weakening the political power of voters from racial and ethnic minority groups who tend to vote for Democrats.

What Is Gerrymandering?

While the concept of gerrymandering can mean many different things to many people, the heart of the idea is that by manipulating the geographic boundaries (eg the shapes) of election constituencies, politicians are able to achieve outcomes that help their personal or political interests.

The term “gerrymandering” was first used over 200 years ago to refer to election boundaries approved by Elbridge Gerry, who, as governor of the state of Massachusetts in 1812, used his power to approve changes that helped his political party win seats.

Critics of the map remarked that the shape of the boundaries looked like a mythological salamander, and coined the map “Gerry’s Salamander.” Since then, “gerrymandering” has become shorthand for the rigging of constituency shapes as a way to achieve power.

In the United States, the practice has become widespread. Every ten years, after the national census is completed, state governments are required by law to revise their congressional and state assembly constituency boundaries so that they are approximately equal in population size and achieve minority representation, among other goals (the precise requirements vary from state to state). This process in the United States is called “redistricting.”

My research suggests that the politicians who control redistricting decisions often use this power to give their political party an unfair advantage in elections. For example, a recent book I co-authored finds that during 2011 redistricting, nearly half of all US state assembly maps were drawn with extreme bias that gave one party a lopsided advantage in elections.

In 2011, the vast majority of these gerrymanders benefited the conservative Republican Party. However, during the last redistricting cycle, which occurred in 2021-2022, the left-of-centre Democratic Party appear to have approved several new gerrymanders.

Expand

How Does Gerrymandering Work?

Gerrymandering occurs almost exclusively in democracies that use single-member districts – that is, when geographic constituencies are assigned one seat each in an assembly. This arrangement often serves the goal of providing local representation in a large and diverse democracy (like India or Canada, for example).

However, it can lead to extreme biases that can help or hurt political parties. Because each consistency only gets one seat, this means that the party that wins the election gets 100% of the seat, while the second-place party gets none.

Depending on how the boundaries are drawn, this makes it possible for a party that received a majority of votes not to win a majority of seats.

In the United States, this has happened a number of times in recent years. During the 2012 US House of Representatives election, Democratic candidates won more than a million more votes than Republicans; yet Republicans managed to win a comfortable majority of seats.

Similarly, in the 2018 elections in Wisconsin, Democratic candidates won a clear majority of votes. Nevertheless, Republicans ended up winning five out of the eight congressional seats up for grabs and won large majorities in the state assembly and state senate elections.

In the case of Wisconsin, the Republicans were able to ensure they won more seats despite their party’s poor performance with voters, thanks to the state’s political geography. Like many other states, there is a stark urban-rural divide in Wisconsin politics.

In general, people who support Democrats, like college-educated voters and racial and ethnic minorities, tend to live in and around major cities, such as Milwaukee. For this reason, Republicans are able to gerrymander Democrats out of power by “packing” Democratic voters into a small number of districts where they win with very large majorities (eg 70-80%). This ends up “wasting” Democratic votes, so Republicans do better in neighbouring districts.

However, political geography alone is not enough to cause gerrymandering.

As my co-authors and I find in our book, what matters most is “who” is drawing the boundaries. In the United States, politicians have historically been in charge of redistricting. When members from one political party are in charge of the process, we tend to see much more gerrymandering.

However, in recent years, a number of states have changed their laws to take control away from politicians by establishing so-called “independent” commissions, staffed by citizens or judges, to draw the district boundaries. Not surprisingly, these states tend to have much less gerrymandering.

Expand

Gerrymandering in India?

The design of democracy in India is similar in many ways to democracy in the US. Both systems use single-member districts to represent geographic constituencies, and both employ a form of federalism, where power is shared between the national and state/territorial governments.

One critical difference is that, while in the US each state is given the freedom to determine its own legislative boundaries (and often they give politicians the power to do this), in India delimitation is controlled by the Election Commission of India (ECI), which establishes an independent delimitation commission, typically staffed by judges – not politicians.

However, as recent delimitations in Assam and Jammu and Kashmir show, politicians can still influence the process. This is because the ECI considers a variety of goals during delimitation. First, it equalises population differences between constituencies.

However, depending on which population data is used, this can lead to dramatically different outcomes. For example, in J&K, the ECI used data from the 2011 census – the most recent results available.

However, in Assam, it will use 2001 population data, which the opposition has charged will lead to an underrepresentation of Muslims, given the rise of the Muslim population in the region in the last two decades. Critiques charge the move is meant to strengthen the power of BJP’s coalition.

As well, the ECI takes into account a region’s geography and administrative districts. This was the justification given for the decision to create six new assembly seats in Jammu (which has a Hindu majority) and only one new assembly seat in Kashmir (which has a Muslim majority), even though the population of Kashmir is larger than that of Jammu.

In this case, the obvious effect of prioritising geographic size is that it decreases Muslim representation in the assembly.

A similar move was made in December last year when Assam chief minister Himanta Biswa Sarma approved an order merging four administrative districts with their parent districts. The timing of this decision raised eyebrows because the districts were only recently created, and because it occurred less than 24 hours before the ECI’s freeze on the redrawing of administrative districts in advance of the delimitation of Assam’s Assembly and Parliamentary constituencies.

This is a classic case of gerrymandering, and the likely impact of this move is a reduction in the political power of Muslims.

Expand

Dangers of Gerrymandering

In many states in the US, politicians have rigged congressional and state assembly boundaries to give their political party a competitive edge in elections. Both of the two major political parties – the Democratic Party and the Republican Party – are guilty of this practice; however, the Republican Party’s gerrymandering has had the most far-reaching consequences.

Because many Republican-controlled states have high levels of racial segregation, Republicans are able to win by weakening the political power of voters from racial and ethnic minority groups who tend to vote for Democrats.

By weakening the power of minority voters on election outcomes, gerrymandering reduces their role in the exercise, thus threatening democracy itself.

Can Gerrymandering Be Prevented With Reforms?

As the examples of delimitation in J&K and Assam suggest, even though the ECI is less prone to produce gerrymanders because judges (rather than politicians) draw the boundaries, this alone is not enough to eliminate gerrymandering altogether.

One of the most effective ways to eliminate gerrymandering is to transition to multimember districts. Rather than assigning single seats to localised constituencies, multiple seats could be awarded to a constituency depending on the population size and geography.

This could allow several parties to win some share of seats in an election depending on their vote share. And if smaller constituencies were merged into larger multi-seat constituencies, this would reduce the number of boundaries to be drawn, limiting the effects of gerrymandering.

However, as we have seen in the US, achieving reforms is an uphill battle. This is particularly true when the ruling party stands to lose power if reforms are adopted.

(Alex Keena is an assistant professor of political science at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) in the United States. A PhD from the University of California, Irvine, he has co-authored two books on gerrymandering in the United States. The views expressed are the author’s own. The Quint neither endorses nor is responsible for them.)