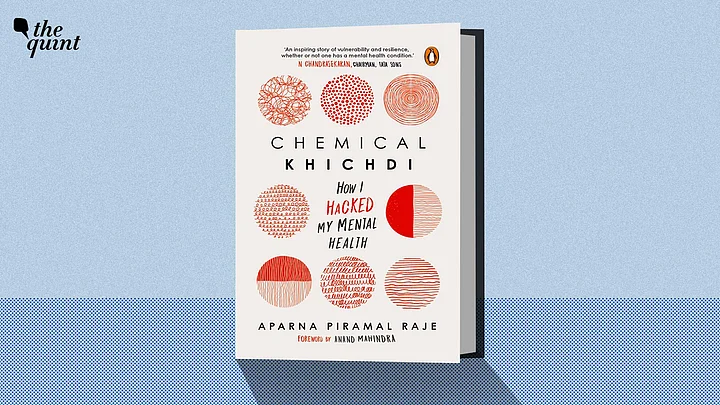

(This is an excerpt from Chemical Khichdi: How I Hacked My Mental Health by Aparna Piramal Raje, published by Penguin Random House. You can buy it here.)

I was 24 then, and had been working in sales and marketing with VIP luggage for three years. Midway through the year, I was accepted into the Harvard Business School. The programme started in September.

In the interim, I planned to take time off from the business, to pursue a different sort of adventure: to intern with Randeep Sudan, a senior bureaucrat in the Andhra Pradesh state government at the time. Mr. Sudan worked closely with N. Chandrababu Naidu, then considered the chief minister of one of India’s most technologically progressive states.

The internship was facilitated by a family friend, and I was keen to learning about state-level governance, a completely unfamiliar subject.

Come July 2000, I found myself in Hyderabad, then the capital of Andhra Pradesh, staying as a paying guest in the home of Lakshmi Devi Raj. Over the next four weeks, I acquired two role models - my innovative and approachable boss, Mr. Sudan, and my hostess, the 68-year old joyful and independent Lakshmi Aunty. During the day, Mr. Sudan ensured I worked on stimulating projects, such as how the state could attract more external investment.

At night, Lakshmi Aunty took me on a cultural and gastronomic tour of Hyderabad’s unique attraction: its larger-than-life parties. Musical evenings went go on all night – I could not keep up with Lakshmi Aunty and her friends.

So it was a successful internship on all counts. My work was appreciated, so much so that Mr. Sudan arranged for me to make a presentation to the Chief Minister and a large team at the end of my four weeks. And two decades later, Lakshmi Aunty continues to remain a sprightly role model and a friend.

Yet inside, there was turmoil. I was consumed with anxiety and insecurity about my parents’ deteriorating marriage. By now it was clear there is a major estrangement, something which I had trouble accepting. I was also deeply unhappy about another relationship break-up, someone I had been seeing for nearly two years. And I was riveted with excitement about the success of my internship.

These emotions triggered the perfect storm.

My mounting excitement – the internship, Harvard - and my raw insecurities made me impetuous, restless and hypomanic. With all the idealism of a 24-year-old, I was convinced I could change the world.

Blurry as the past can be, I can still remember some of the half-baked thoughts and ideas that overtook my mind in the weeks before I was due to leave for Boston.

I knew I could catalyze an omnipotent coalition of Indian companies and the government to rule global markets in the prevailing dotcom era, and started drawing up grandiose plans, scribbling away on bits of paper.

Sleep disappeared, as I felt invincible, restless and impetuous, going to bed late and rising early.

Kay Redfield Jamison, a renowned psychotherapist, bipolar patient and author of the classic An Unquiet Mind, says it best in her memoir. “My mind was beginning to have to scramble a bit to keep up with itself, as ideas were coming so fast that they intersected one another at every inconceivable angle.

There was a neuronal pileup on the highways of my brain, and the more I tried to slow down my thinking the more I became aware that I couldn’t.”

My family was shocked at my behavioural change. “I know you so well, I've grown up with you. We shared a room for years. So to watch your face change, your eyes change, your mind change, in front of my eyes, was a terrifying experience."

"If you behave your whole life one way and then suddenly start behaving another way, and you maintain that the new way is the real you, and Mom and I are saying, “No, something’s wrong, something's different,” but you're holding on to your mood as the authentic truth, it creates a friction like no other."

"Because we're saying something's wrong. And you're saying nothing is wrong. That was the biggest clash. We didn’t know what it was, we were totally in the dark,” recalls my sister Radhika.

Welcome to bipolarity.

Even though we did not acknowledge it as such at the time, it was clear that by August, that my thoughts, my emotions – and crucially, my sleep – were completely out of control.

It was also obvious that I could not travel on my own, and my mother and sister accompanied me to Boston. We arrived at immigration only to find that my hypomanic mind had left a crucial piece of official documentation at home. It was like showing up for the World Cup cricket without the match tickets! Luckily, the immigration officer allowed me into the country without it.

Eventually my racing thoughts subsided, I settled into my dorm room, made it to my classes, and forged some sort of routine. Mom and Radhika left and the depression set in.

HBS is known for its luxurious campus and active student body. After classes, students play tennis, they go running, meet in the club-style lounge or even solve the next day’s cases.

I did none of that. At first, I locked myself into my dorm room after classes, and cried. I wept for my recently broken relationship, I wept for my parents’ fading marriage, I wept for the aching feeling of loss inside me.

Later, I stopped crying, stared at the ceiling and listened to Sting’s Ghost Story on repeat. (I liked its line “What did not kill me just made me stronger.”

It was my mantra at the time. I know there’s a backlash against that line now, but back then I drew strength from it)

The room was small, just enough to house a bed, a wardrobe and an oversized music system. It opened into a common study that I shared with a roommate, Louise, a girl from Scotland with many of the same books as me, on her bookshelf, who soon became a close friend.

Our desks overlooked a garden of trees, expertly maintained by HBS’s legendary landscaping team.

As the seasons changed, the New England autumn nourished me with its magic, drawing me outdoors. I went for hikes and short road trips to see the fall colours, enjoyed a river rafting trip with my classmates.

Eventually, I became more engaged with school academics and activities, and found a group of classmates who also turned into lifelong friends. I began seeing a counsellor on campus, which helped to some extent.

August 2001

Back home for a summer break between my first and second years of business-school, I am at a cousin’s engagement party in our family home, wearing a light pink ghaghra that contrasts with the red-hot rebellion brewing inside me. There is dancing, music, poetry and dinner, but my mind is swaying to a tune of its own. Negative emotions are building up inside me like expanding steam. Perhaps I am angry because my recently concluded summer internship at an investment bank has not gone well – I did not get a job offer. Perhaps I am still upset about the situation at home. Whatever the reasons, my behaviour deteriorates towards the bizarre – I am restless and impulsive. My mother, sister and I retreat to a family member’s beachhouse to try and calm me down, where I stay up all night talking to myself. When my father asks me later

‘what goes through your mind at these times?’, I say – ‘it’s like there’s a script, and I need to act on it.’ Over a few days, my equilibrium is restored, and I make it back to school just in time for the start of the second year.

In my second year, I lived off campus, in a house with three girls. We were close friends, but there were times when the melancholy would re-emerge, often prompted by loneliness.

I remember a quiet weekend, when everyone was out. I looked out of the kitchen window, held a knife to my wrist, and thought – this is all it would take.

But then I reminded myself that “this” would take forever, for me to bleed to death. Instead, I came across Moth Smoke on my bookshelf, a novel by British-Pakistani author Mohsin Hamid, that captivated me for the rest of the weekend.

So much so that I later told a close friend and classmate, “it was the worst weekend of my life, but then it turned out to be one of the best.”

Personalised projects made me happier. I realised I enjoyed research-led field studies rather than conventional classes, and pursued these options as much as possible.

Supervised by individual professors and done either singly or in groups of two and three students, the field studies allowed to collaborate with my friends and get closer to them, whilst exploring my research interests.

I also signed up for a life-changing creative writing class with the Harvard undergraduates, across the Charles river, held every week in a small room with a large square table and stained-glass windows, and became more regular at yoga. In the end, the depression wore off naturally, without medication, and I graduated without incident, with my classmates

(Aparna Piramal Raje is the author of Working Out of the Box: 40 Stories of Leading CEOs. She is a regular columnist with Mint. She contributed to the UK's Weekend Financial Times, a global publication, for several years in the past.)