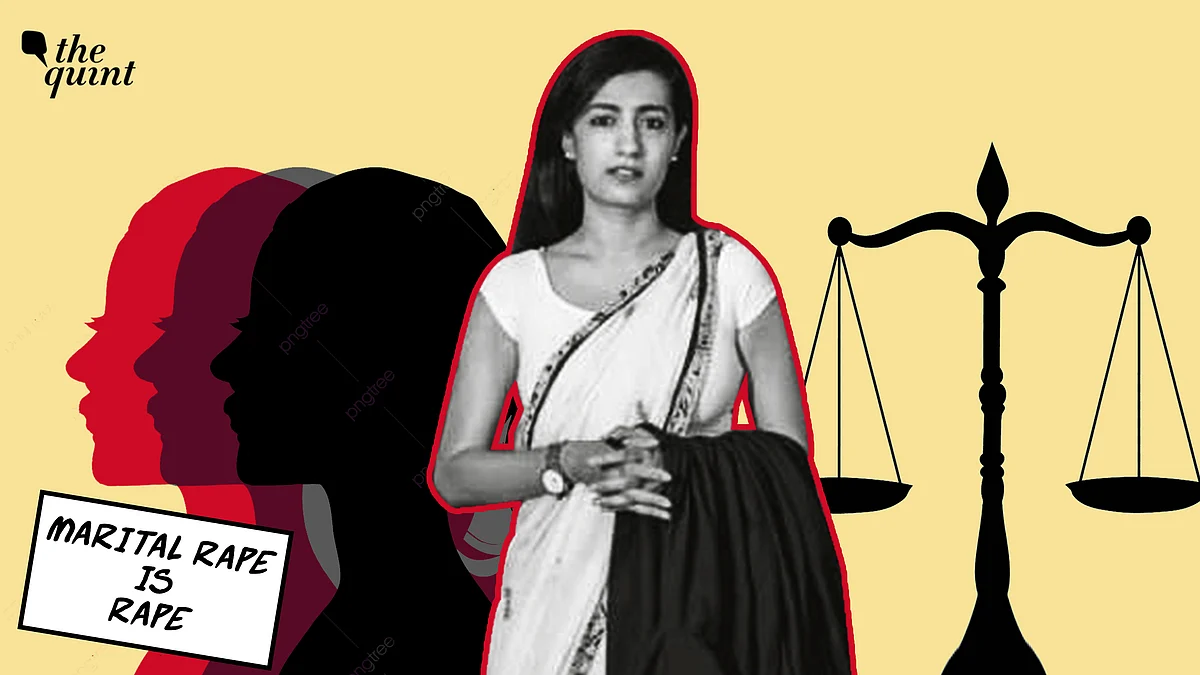

'Every Day Is Justice Denied': Karuna Nundy on Marital Rape Split Verdict

"It is a blot on this nation. And in my personal opinion, it is a blot on the Constitution of India."

advertisement

Video Editor: Rajbir Singh

Reputed advocate Karuna Nundy led the fight against the marital rape exception in the Delhi High Court for the last several years, and will continue to fight the case as it goes forward, after the court on 11 May delivered a split verdict on the controversial provision in the Indian Penal Code.

Section 375 of the IPC defines the offence of rape, with Exception 2 to the section saying: "Sexual intercourse or sexual acts by a man with his own wife ... is not rape."

This marital rape exception was challenged in the Delhi High Court by the RIT Foundation and the All India Democratic Women's Association – who were represented by Nundy – with additional petitions also filed by survivors of marital rape. They argued that the exception violates the fundamental rights of married women and should be struck down.

"It's been a long struggle," Nundy, who is well known for her advocacy on women's rights, told The Quint, adding that there were two rounds of arguments and with the status quo remaining in force thanks to the split verdict, "every day is justice denied".

Is the Split Verdict a Disappointment?

"With a a matter like this, one's personal feelings are largely irrelevant. I am not saying one doesn't have them, I am saying they are not relevant because women are being raped while we speak," Nundy said.

Exception 2 to Section 375, by implication, gives husbands a right to commit rape upon their wives, she contends.

She even notes that thanks to well-meaning amendments to the definition of rape, to include anal rape for instance, married women have actually lost the ability to file cases which they could before, since the marital rape exception takes anything in the definition of rape and says it is not rape if done by a husband.

Section 377 of the IPC, for instance, could have been used prior to the amendments to file a case for forced anal sex by a married woman, but the marital rape exception now covers this as well.

"This is a burning problem. It's a blot on this nation. And in my personal opinion, it is a blot on the Constitution of India," Nundy argued.

Does Justice Rajiv Shakdher's Opinion Provide Hope for Getting Rid of the Marital Rape Exception?

Justice Rajiv Shakdher, in his judgment, held that the marital rape exception violated the fundamental rights of married women including under Article 14 (the right to equal treatment) and Article 21 (the right to life and personal liberty). As a result, he concluded that the exception should be struck down.

"I will say that Justice Shakdher's judgment is very robust as per the current constitutional scheme," Nundy suggested.

She noted that it was in line with recent judgments of the Supreme Court including the nine-judge right to privacy judgment, as well as decisions in the Joseph Shine (abolition of adultery in IPC), Navtej Johar (decriminalisation of consensual homosexual acts) and NALSA (rights of transgender persons) cases.

"There are so many judgments that are very very clear on women's sexual autonomy, bodily integrity and intimate decision-making. NALSA is very clear on the fundamental right to sexual expression," she explained.

Nundy thinks that the extensive questioning in the case, and the way in which those who argued for the exception to go built upon their arguments as a result, not only helped Justice Shakdher arrive at his decision, but may also "serve the cause" in the Supreme Court.

Was Justice Hari Shankar Right to Say That There is an 'Intelligible Differentia' Created by Marriage?

A crucial element of Justice C Hari Shankar's opinion – which held that there were no grounds to strike down the marital rape exception – was that there is an 'intelligible differentia' created by marriage, which means that there was no violation of Article 14 (right to equal treatment before the law).

While Nundy declined to comment on the rights and wrongs of the opinion, she noted that in her written submissions, which were cited by Justice Hari Shankar, she had agreed that an 'intelligible differentia' between married and unmarried women did indeed exist.

She said that this will be elaborated on in the next stage of proceedings.

Could the Central Govt & Parliament End the Marital Rape Exception Rather Than Wait for the Courts?

"The Government of India – in the end – saying that we're not going to take a stand against you, is something that indicates that perhaps they are considering the issue," Nundy observed. "Obviously this doesn't take the need for speed off."

The Centre did not oppose the plea to strike down the marital rape exception in the Delhi High Court, telling the bench that it was reviewing the exception as part of its review of India's criminal laws.

She suggested that a good approach to dealing with this kind of situation to get rid of an unjust law was taken by the Supreme Court when it came to the sedition case, by staying the operation of the law and telling the government to get back to them within a short deadline.

Parliamentary panels and the Law Commission, when they considered this issue in the past, have rejected suggestions to get right of the marital rape exception in the name of protecting the institution of marriage.

Nundy, who had been involved with the Justice JS Verma Committee's recommendations to amend India's rape laws, believes that things have improved since 2013, when the Committee's suggestion to remove the marital rape exception was rejected.

"I think that since 2013, it's now been practically a decade, and thinking around equality has moved on. I also think that the government taking a non-stand like they did, would have been unlikely before," she said.