Personal Is Always Political: What True Intersectional Sex-Positive Feminism Is

Book Excerpt: When we see consent as the sole constraint on ethically OK sex, we end up ignoring political facts.

advertisement

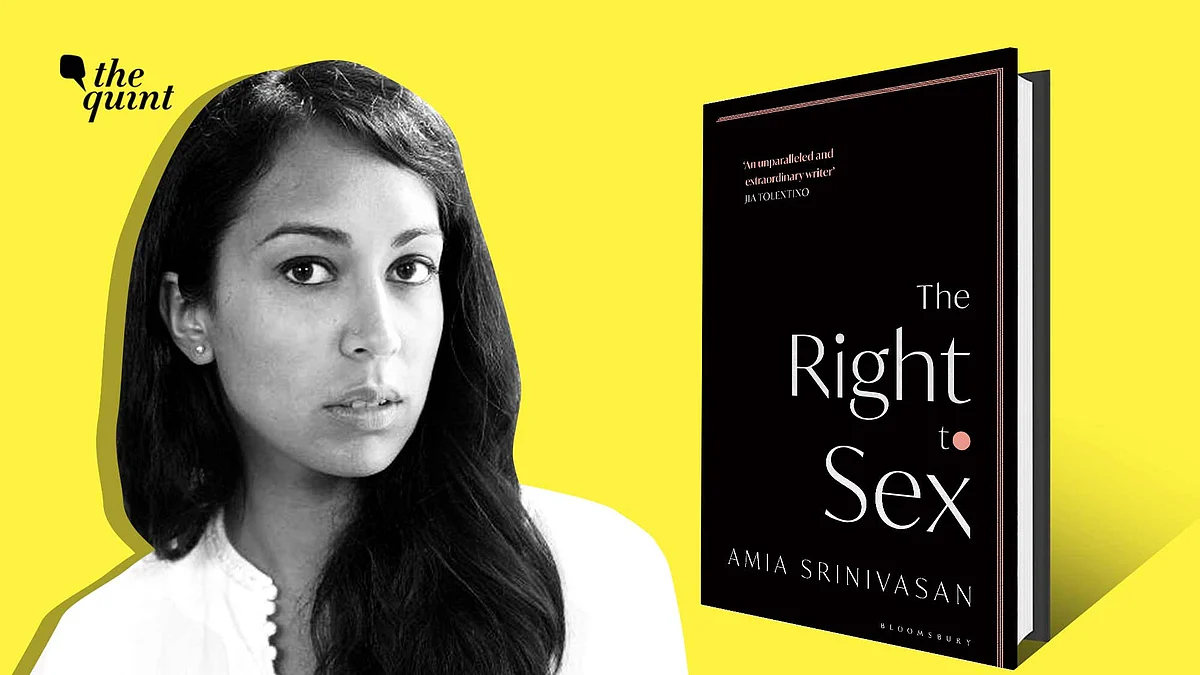

(This excerpt has been taken with permission from ‘The Right to Sex’ by Amia Srinivasan, published by Bloomsbury Publishing. Srinivasan is a philosopher and a Chichele Professor of Social and Political Theory at the University of Oxford.)

As the women’s liberation movement unfolded through the 1970s and into the 1980s, these battle lines hardened. From the mid-1970s onwards, anti-sex feminists in the US, and to a lesser extent revolutionary feminists in the UK, became increasingly focused on the issue of pornography, which came to symbolise for some feminists the whole of patriarchy. (In keeping with the theme of feminist homophobia, anti-porn feminists were, on the whole, also virulently opposed to lesbian sadomasochism, which they thought recapitulated patriarchal dynamics.)

How Ellen Willis Led the Development of ‘Pro-Sex’ or ‘Sex-Positive’ Feminism

But many feminists also wanted to distance themselves from the pro-woman line that the ideal state for most women was monogamous heterosexual marriage.

Both forms of feminism, Willis wrote, asked ‘women to accept a spurious moral superiority as a substitute for sexual pleasure, and curbs on men’s sexual freedom as a substitute for real power.’ Drawing inspiration from the contemporaneous LGBT rights movement, Willis and other pro-sex feminists insisted that women were sexual subjects in their own right, whose acts of consent – saying yes and saying no – were morally dispositive.

Since Willis, the case for pro-sex feminism has been buttressed by feminism’s turn towards intersectionality. Thinking about the ways patriarchal oppression is inflected by race and class has made feminists reluctant to make universal prescriptions, including universal sexual policies.

‘The Important Thing Now Is To Take Women at Their Word’

The demand for equal access to the workplace will be more resonant for white, middle-class women who have been expected to stay home than it will be for the black and working class women who have always been expected to labour alongside men. Similarly, sexual self-objectification may mean one thing for a woman who, by virtue of her whiteness, already conforms to the paradigm of female beauty, but quite another thing for a black or brown woman, or a trans woman.

The turn towards intersectionality has also deepened feminist discomfort with thinking in terms of false consciousness: that’s to say, with the idea that women who have sex with and marry men have internalised the patriarchy. The important thing now, it is broadly thought, is to take women at their word.

This is not merely an epistemic claim: that a woman’s saying something about her own experience gives us strong, though perhaps not indefeasible, reason to think it true. It is also, or perhaps primarily, an ethical claim: a feminism that trades too freely in notions of self-deception is a feminism that risks dominating the subjects it presumes to liberate.

'There Are Limits to What Can Be Understood About Sex From the Outside'

The case made by Willis in ‘Lust Horizons’ has so far proved the enduring one. Since the 1980s, the wind has been behind a feminism which does not moralise about women’s sexual desires, and which insists that acting on those desires is morally constrained only by the boundaries of consent.

It would be too easy, though, to say that sex positivity represents the co-option of feminism by liberalism. Generations of feminists and gay and lesbian activists have fought hard to free sex from shame, stigma, coercion, abuse and unwanted pain.

‘To Say Sex Work Is ’Just Work’ Is To Forget That All Work Is Also Sexed’

Yet it would be disingenuous to make nothing of the convergence, however unintentional, between sex positivity and liberalism in their shared reluctance to interrogate the formation of our desires. Third-wave feminists are right to say, for example, that sex work is work, and can be better work than the menial labour undertaken by most women.

And surely there will be related things to say about other forms of women’s work: teaching, nursing, caring, mothering. To say that sex work is ‘just work’ is to forget that all work – men’s work, women’s work – is never just work: it is also sexed.

Are Women's Sexual Choices Really Free? Why Do We Choose What We Choose?

Willis concludes ‘Lust Horizons’ by saying that for her it is ‘axiomatic that consenting partners have a right to their sexual proclivities, and that authoritarian moralism has no place’ in feminism. And yet, she goes on, ‘a truly radical movement must look . . . beyond the right to choose, and keep focusing on the fundamental questions. Why do we choose what we choose? What would we choose if we had a real choice?’ This may seem an extraordinary reversal on Willis’s part.

But perhaps she has given with both. Here, she tells us, is a task for feminism: to treat as axiomatic our free sexual choices, while also seeing why, as ‘anti-sex’ and lesbian feminists have always said, such choices, under patriarchy, are rarely free. What I am suggesting is that, in our rush to do the former, feminists risk forgetting to do the latter.

Why Consent Should Not Be the Sole Constraint on 'Ethically OK' Sex

When we see consent as the sole constraint on ethically OK sex, we are pushed towards a naturalisation of sexual preference in which the rape fantasy becomes a primordial rather than a political fact. But not only the rape fantasy.

Consider the supreme fuckability of ‘hot blonde sluts’ and East Asian women, the comparative unfuckability of black women and Asian men, the fetishisation and fear of black male sexuality, the sexual disgust expressed towards disabled, trans and fat bodies.

They are facts that a truly intersectional feminism should demand we take seriously. But the sex-positive gaze, unmoored from Willis’s call to ambivalence, threatens to neutralise these facts, treating them as pre-political givens.